Showdown on West Coast Docks: The Battle of Longview

(November 2011).

click on photo for article

Chicago Plant Occupation Electrifies Labor

(December 2008).

click on photo for article

May Day Strike Against the War Shuts Down

U.S. West Coast Ports

(May 2008)

click on photo for article

July 2022

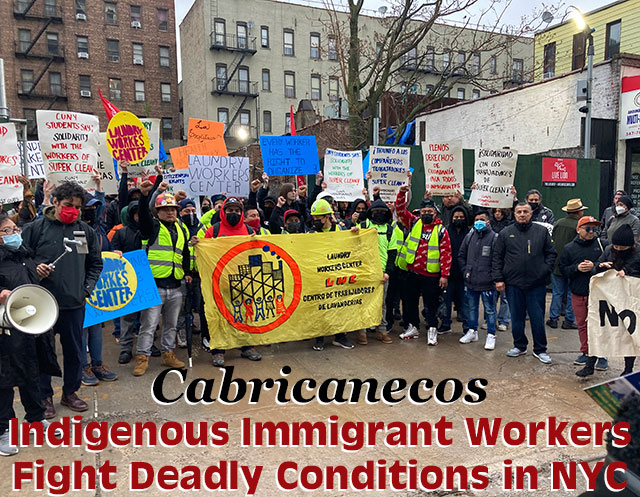

¡Todos parejos! Equal for All!

Launch of organizing drive of indigenous immigrant construction workers in New York City, May 2.

(Internationalist photo)

By Trabajadores Internacionales

Clasistas /

Class Struggle International Workers

BROOKLYN, NY – Facing flagrant management abuse and a wave of retaliatory firings, a courageous campaign by 40 demolition/construction workers – mainly indigenous immigrants from Guatemala and Mexico – shines a spotlight on deadly dangerous conditions on the job faced by many thousands in the New York area and beyond. “We are human beings, but they use us up and then just throw us away,” a worker who suffered multiple injuries unloading heavy materials for Best Super Clean/ISK Group said, echoed by fellow campaign activists during a collective interview with The Internationalist.

Poster announcing campaign launch on “Liberation Day,” May 2 . (Photo: Laundry Workers Center)

Best Super Clean/ISK does construction-site clean-up and demolition. The company refuses to provide its workers with adequate equipment on the job, or even the most basic tools they need. “The owners are making millions from our labor, but they treat us as if we have no worth or value,” said another worker active in the campaign. Organized by the Laundry Workers Center (LWC), the campaign, presently focused on winning key improvements in job conditions and wages, is called “Cabricanecos,” because many of the workers are originally from the town of Cabricán in Guatemala.

“Tools and safety on the job” are central to the struggle, emphasized compañeros Luca and Wilmer, two leaders of the campaign. Many kinds of unsafe conditions are “part of our work every day” and need to end, said compañero Cesáreo. “They treat us like garbage and even talk to us as if we were animals,” sometimes calling the workers dogs and other vile and degrading insults. “We want them to stop doing that,” he said. “Too many injustices,” added Luca. In addition to tools and job safety, workers’ key demands also include the rehiring of five workers fired in reprisals against organizing; a pay raise; sick days, lunch hours on a set schedule, and breaks as required by law. (“What do you need breaks for?” is a typical jibe from company managers.)

Best Super Clean/ISK – whose properties also include a video surveillance operation called Live Lion Security – typifies many non-union contracting firms that make a mint paying immigrant workers poverty wages to clear debris at construction sites. Workers report that the company’s profits have grown so much in the recent period that it was able to increase its fleet of trucks from 4 to around 30. Since the workers launched their campaign publicly with a dramatic rally at the company’s truck dispatch site on May 2, Best Super Clear/ISK has faced repeated protests outside a sign-less building in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood that serves as its HQ.

New Link in a Chain of Struggles

Workers leafleting in organizing campaign. (Photo: Laundry Workers Center)

The Cabricanecos campaign was initiated by a group of workers that includes veterans of the organizing drive by immigrant warehouse workers at B&H Photo, also led by the LWC.1 “We took that experience into this struggle here,” one of them explained during the collective interview with The Internationalist. The B&H struggle was in turn sparked by immigrant workers’ fight to unionize the Hot and Crusty restaurant in midtown Manhattan almost a decade ago.2 After unionization won at B&H in 2016, the company, in a flagrant union-busting move, closed warehouses the following year.3 Some of those laid off there found work in construction and demolition.

Thus the Cabricanecos campaign is a link in a chain of struggles underlining both the need and the great potential for militant organizing among sectors of immigrant workers who are key to making the city run, at the same time as they are denied basic rights and treated as “undocumented” pariahs while often risking their lives due to intolerable working conditions.

Most of the time such conditions go under the radar, rarely making it into the headlines. An exception came last month when a building in the Bronx acquired grim but fleeting notoriety in an exposé titled “The Men Lost to 20 Bruckner Boulevard” (New York Times, 30 May). An old building being transformed into a charter school, it is “one of the deadliest construction sites in New York City,” the paper reported. Last year the bosses’ criminal negligence claimed the life of Mexican immigrant Mauricio Sánchez and gravely injured Yonin Pineda, from Guatemala, when an elevator crashed as they were trying to take “waist-high containers of construction debris” down five flights; three years previously a teenage immigrant worker from Ecuador, Marco Martínez, was killed when a mechanical lift crushed him against a ceiling.

“While government inspectors have issued numerous violations in connection with the deaths,” the Times reported, “they have exacted just $28,864 in fines.” Meanwhile, shortly after the most recent fatal incident, the building’s owner “treated dozens of friends to a days-long celebration of his 50th birthday” on an island vacation spot, among them “his development partner in the Bronx Project and the founder of the charter school that had signed a long-term lease on the building.” There are thousands of non-union sites like the one on Bruckner throughout the city, where the need to organize for even the most elementary rights of labor is quite literally a matter of life and death.

As for the activists of the Cabricanecos campaign, what they have begun in launching their campaign early last month is a fight that is in the interests of the whole working class, in New York and beyond. Helping them win, and helping extend the struggle to the thousands facing similar conditions, is a crucial duty of the labor movement as a whole, which can and must bring its power into the fight.

Twelve Floors Up Without a Harness

Voicing workers'

demands at campaign launch, May 2. (Internationalist photo)

Voicing workers'

demands at campaign launch, May 2. (Internationalist photo)Whether it is to clear rubble or even knock down walls, the company “doesn’t give us shovels, picks, crowbars, gloves, masks” or other necessary items – “not even garbage bags or cans” to put debris in, Luca said. Instead, workers have had to look for “junk tools” that have been thrown away, or get cheap plastic ones that break easily.

As an example of conditions the workers face, Wilmer described the bosses sending them to remove the roof from a 12-story building. They were ordered to take the pieces down on scaffolding, with no harnesses, no training, and without the scaffold user certification card required by the city. “So much pressure, without tools, they don’t worry about the workers.” The bosses send workers to “take out huge pieces of wood, almost with our bare hands; and when they tell us to remove sheetrock, or walls get knocked down, the dust rises all around us, but we have no protection,” another worker noted; sometimes workers’ faces “are covered with sheetrock dust.”

Meanwhile the workers make “poverty pay.” Managers often told them that before a work group could take lunch, they would have to fill at least half of a truck with the debris the company was getting paid to clear away. “Sometimes this meant we had to wait until 3 or 4 in the afternoon, after starting at 7 in the morning,” another activist noted. Breaks are often non-existent. “‘Faster, faster,’ they yell at us,” often amidst a hail of insults.

Eventually, a group of workers got together in one of the compañeros’ home. A few knew Mahoma López, a leader of the Laundry Workers Center, from the time of the B&H campaign. They decided to get in touch. The workers began to “join together, to talk amongst ourselves,” recounts Cesáreo, and to ask: “What can we do in the face of all this exploitation? It isn’t right.”

The Cabricanecos organizing drive goes back considerably before the campaign was announced publicly this May. Workers described as a turning point the action they took in the summer of last year. “We stopped working and protested in the area where they keep the trucks,” one of the activists told us. “The owner came and asked what we wanted. We said, ‘We want a raise. We want $17 per hour’.” (Pay was $15/hour at that time.) “The boss said he would give different raises to different groups of workers, like as little as 25 cents more for the new people.”

“We said: No. ¡Todos parejos! [all equal], 17

an hour, all equal because we all do the same work.” The

firm charges other companies “a lot more than that” per

hour for the clean-up work its employees carry out.

While not accepting the demand, management said some

kind of raise would be forthcoming. But the workers

stopped work a second time – and then the company raised

pay to $17, but still not for everyone. (Some got only a

dollar raise, while new hires still get $15.) Meanwhile,

at some other companies in the same industry, “workers

are getting 21, 23, 27 dollars an hour.” Today the

Cabricanecos campaign is demanding a big and equal raise

for all. Todos parejos.

Police open way for trucks out of Best Super Clean site as demonstrators rally to support Cabricanecos organizing drive. (Internationalist photo)

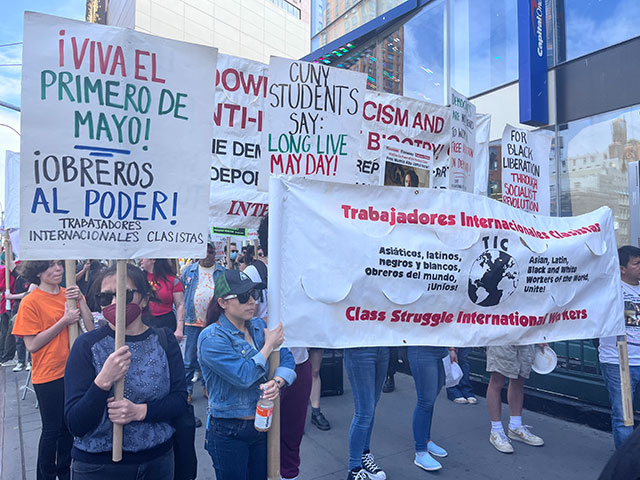

This year on May Day, the workers marched together as part of the Laundry Workers Center contingent, as supporters chanted: “Cabricanecos, ¡estamos con ustedes!” (Cabricanecos, we are with you!) Then, on the morning of May 2, the campaign’s public launch – titled Liberation Day – was carried out. At 6:00 a.m. workers massed at a large lot in Brooklyn’s Crown Heights neighborhood where the company keeps its trucks, while supporters gathered in a nearby park, then marched to the site. In addition to Laundry Workers Center activists and a sizable Internationalist contingent (including many students from the City University of New York), there were labor, community and left groups, among them jornaleros (day laborers), Workers World Party, Industrial Workers of the World and others. Amid a heavy downpour, militant chants of solidarity ruptured the early-morning silence.

Trucks were unable to get past the rally and leave the lot. Nor was the car of a manager, who refused to accept the workers’ carta de demandas (letter listing their demands). “Accept the letter, accept the letter,” chanted the crowd. “They’re afraid to take the letter,” people yelled out. Internationalists chanted, “Los patrones tienen miedo porque los obreros no lo tienen” (The bosses are afraid, because the workers are not), and the slogan was picked up by the crowd. The company called the NYPD, who – doing their job of upholding the interests and property of the exploiting class – eventually cleared the way for the manager’s car and some trucks to drive through. Almost two hours had passed since the rally began. The campaign had definitely been launched.

Indigenous Immigrants: A Growing Part of NYC Workforce

Many delivery workers in New York City are immigrants from Guatemala and indigenous areas of Mexico. Protest of Deliveristas Unidos, October 2020. (Photo: Sol Aramendi / Workers Justice Project)

The workers involved in the campaign come from many countries, including Guatemala, Mexico, Ecuador, El Salvador, Honduras and Colombia. “It doesn’t matter where you come from,” Cesáreo said, they all work together and are determined to defend their rights. Like several other campaign activists who are originally from the southwestern Mexican state of Guerrero, Cesáreo is a member of the Tlapanec indigenous people. Proudly multilingual, he speaks the Mixtec and Náhuatl indigenous languages in addition to Tlapanec and Spanish.

“Cabricanecos” is the name that the whole workforce involved in the Best Super Clean struggle uses for their campaign. This too is an expression of solidarity amongst this multinational workforce. The name was chosen originally since “a lot of us are from Cabricán, in Guatemala,” notes Wilmer. Their mother tongue is Mam, part of the Maya family of languages.4 A municipality in the department (province) of Quetzaltenango, “Cabricán is a town, it is a land, of minas de cal [lime mines],” Luca explained, showing us a lively online video about this.5 This mineral has a wide range of uses, from the preparation of corn for tortillas to the production of plaster and other construction materials. In Cabricán, many of the compañeros used to work as lime miners.

Immigrants from Guatemala are a growing part of New York’s working class. Census figures for 2010 stated there were over 100,000 Guatemalans in the New York metropolitan area as a whole. In NYC specifically, their numbers grew to over 32,000, increasing by almost 50% from 2010 to 2019, making this the fastest-growing Latino immigrant group in the city.6 And while nearly three quarters of Latin American immigrants in the NYC workforce are essential workers as defined by New York State, “Guatemalans and Mexicans had the highest share” (84 and 78 percent respectively). Yet Mexican and Guatemalan immigrants are more than twice as likely to live in overcrowded housing than the overall rate for NYC immigrants, have the highest share classed as “undocumented” among Latino immigrant groups, and face many other intolerable indices of oppression and discrimination.

Linguistic and ethnic discrimination against indigenous Latin American immigrants is one of the factors that has led to their frequently being undercounted. A significant number report being afraid or reluctant to be identified as indigenous. Up-to-date estimates are lacking, but as of 2017, figures for the U.S. as a whole showed an almost five-fold growth since 1990, to a (conservative) estimate of over 565,000 indigenous Latin American immigrants.7 Among indigenous working people in New York City, there are significant numbers of Kichwa speakers from Ecuador, Afro-indigenous Garifuna people from Honduras, and many others, including a growing proportion of immigrants who come from Mexico (with some estimates approaching 20%) and from Guatemala.

Like other largely agricultural regions in Mexico, the state of Guerrero faced devastating effects from the North American “Free Trade” Agreement, which went into effect in 1994. Flooding Mexico with heavily subsidized, industrially farmed U.S. corn and other products, NAFTA made subsistence impossible for vast numbers of the rural poor.8 This was a key factor accelerating out-migration to the U.S. from Guerrero, which, among Mexican states, has the fourth largest percentage of people who speak indigenous languages.9

A study of “histories of dispossession of one of the newest migrant groups in NYC,” indigenous immigrant workers from the La Montaña region of Guerrero (an area with a high proportion of indigenous people), notes that NAFTA’s effects were exacerbated by “state violence through the militarization of Guerrero” as part of the U.S.-fueled “drug war” in Mexico. Having previously served as a “supplier of seasonal indigenous day labor for the agribusiness sector in the northwest of Mexico,” the Montaña region “was transformed into a labor force supplier for the North American migrant labor market.”10

At the time of the unionization campaign at the B&H warehouses, where many of the workers were of Mixtec origin, CUNY Internationalist comrades visiting Mexico recorded a message of solidarity with the B&H workers in Mixtec and Spanish, from a striking member of Mexico’s militant teachers movement.11 He was from Oaxaca, the southern Mexican state with a long history of labor/indigenous struggle, which was also the birthplace of the first indigenous president of any country in Latin America: Benito Juárez (1806-72), who led the Reforma against the power of the Church and in 1867 defeated France’s attempt to conquer Mexico.

Yet discrimination against indigenous people continues to be a bitter reality. “When you speak your language, sometimes what happens when you go to the city is that people criticize you for being indigenous,” one of the Tlapanec Best Super Clean workers told us during the interview. “That’s why we are sometimes afraid to say that we speak our language,” though “many of us speak different languages, like Mixtec, Tlapanec, Náhuatl” and others.

With regard to Guatemala, it has a higher proportion of indigenous people (41%, according to United Nations figures for 2018) than any other Latin American country except Bolivia. After a U.S.-organized coup ousted a left-leaning nationalist president in 1954 for the “crime” of nationalizing some unused land held by the United Fruit Company, the country was ruled by a series of U.S.-armed military regimes. Anti-indigenous racism was key to the terror. This culminated in literal genocide in the late 1970s and the ’80s, in which hundreds of thousands were killed, at least 1.5 million displaced, and innumerable indigenous villages were wiped out as part of the dirty wars of U.S.-orchestrated counterinsurgency in Central America.

This is the background for the situation of recent years in Guatemala. A 2018 photo essay titled “Why Are So Many Guatemalans Migrating to the U.S.?” answered that many “are fleeing circumstances that are American-made.” Having spent decades among the Mam indigenous people in northern Guatemala, the author emphasized:

“[P]olicies and U.S. political interventions of the past – and the present – have led to malnutrition, maternal and infant mortality, fractured communities, deep-rooted violence and corruption, and the loss of loved ones among Indigenous peoples living in the highlands. Those who leave for the U.S. are fleeing these conditions, which have been inflicted upon them….”

– Sapiens magazine (25 October 2018, emphasis in original)

While the capitalist politicians block desperate refugees at the border, whipping up racism amid the periodic xenophobic panics and immigration “crises,” the essay’s author notes that many of the Guatemalans she has spoken with, and who face this situation due to U.S. actions, made the point that “they fit the conditions for asylum.”12

Victory to the Cabricanecos Workers’ Struggle!

On May Day, Trabajadores Internacionales Clasistas and Internationalist demonstrators chanted “Cabricanecos, ¡estamos con ustedes!” (Cabricanecos, we are with you). (Internatioinalist photo)

Long active in organizing drives and campaigns among immigrant workers, the Internationalist Group and Trabajadores Internacionales Clasistas emphasize that the power of the whole workers movement must be brought to bear in the fight to stop deportations and for full citizenship rights for all immigrants. This call will be of great importance in the coming period, in which threats and dangers to workers and oppressed people will continue to multiply. Workers solidarity is key.

Since the campaign was launched on May 2, supporters have repeatedly come out to help publicize its demands. The workers have intensively leafleted in the surrounding community. On June 15, Jews for Racial and Economic Justice helped organize a delegation that included six local rabbis, which presented a letter supporting the workers to the company, which is Hasidic-owned.

The Cabricanecos’ struggle comes at a moment when large numbers of workers and youth have been inspired by organizing efforts at Amazon and elsewhere; when inflation is eating away at already skimpy paychecks, one basic right after another is under attack, and the many-sided crises of U.S. capitalist society keep getting sharper. Crumbling imperialist “democracy” says workers like those who have launched this campaign are essential – which they are – yet treats them as disposable pariahs. Its ruling parties, Democratic and Republican, will not even allow the “undocumented” workers, who are key in a broad range of industries, to vote. If one thing is certain, it is that no salvation will come from the politicians of the exploiting class.

Yet struggles like the one courageously launched by triply oppressed indigenous immigrant workers in New York can and should help spark a militant counteroffensive in which the workers and oppressed, bringing out their own power in their own class interest, open their own path to victory. Organizing the unorganized through mass militant struggle is a key part of this perspective.

Echoing his compañeros, one of the indigenous immigrant demolition-construction worker activists sought to hammer home a message: “We came here to work. We are here and we are fighting. If we don’t defend our rights, the same abuses will be carried out against those who come after us. It is for the people who come after us in the future that we will keep fighting, hasta el final (to the end)." ■

To make a contribution to the Cabricanecos campaign, see The Laundry Workers Center or write laundryworkerscenter@gmail.com

- 1. These struggles were covered in depth in our press, including in “V-I-C-T-O-R-Y! B&H Workers in Big Win for Labor and Immigrant Rights,” The Internationalist No. 42, January-February 2016; and “NYC: Immigrant Workers Rebel,” Revolution No. 12, March 2016.

- 2. See “Hot and Crusty Workers Win with Groundbreaking Contract,” The Internationalist special issue, November-December 2012.

- 3. See “De Blasio Administration Complicit in Closing of B&H Warehouses,” The Internationalist No. 48, May-June 2017.

- 4. The Mam people are the fourth largest of the 22 Maya ethnic/linguistic groups in Guatemala.

- 5. “La mina de cal (La Pedrera), Cabricán, Quetzaltenango.”

- 6. Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs, “A Demographic Snapshot: NYC’s Latinx Immigrant Population,” October 2021.

- 7. Sebastián Villamizar-Santamaría, “Racial and Ethnic Composition among Latinos in the United States (1990-2017),” CUNY Center for Latin American, Caribbean and Latino Studies, May 2022.

- 8. Even mainstream bourgeois media have had to acknowledge this fact; see, for example, “Mexican farmer’s daughter: NAFTA destroyed us,” CNN Business, 9 February 2017; and “Want to understand the border crisis? Look to American corn policy,” The Counter, 24 July 2018.

- 9. Almost 16% of the population of Guerrero speaks indigenous languages, according to figures for 2020 published by Mexico’s statistical/geographical agency (cuentame.inegi.org.mx). Guerrero is also where, in September 2014, the 43 students of the Ayotzinapa teachers college, many of them of indigenous origin, were “disappeared” in an act of state terror.

- 10. Rodolfo Hernández Corchado, “From the Montaña to the city: a history of proletarianization of Mixteco indigenous from Guerrero, Mexico to New York City,” Dialectical Anthropology (2018).

- 11. See “In Mexico: Revolutionary Internationalism Up Close,” Revolution No. 13, November 2016.

- 12. For the revolutionary program for workers action defending refugees and migrants, put forward by the Internationalist Group/League for the Fourth International, see, for example: “Border Flashpoint in the Racist War on Immigrants: We Say: Let Them In – Free Them All – Let Them Stay!” and accompanying materials in The Internationalist No. 54, November-December 2018.