December 2007

Revolutionary Leadership Is Key

Internationalist Class Struggle

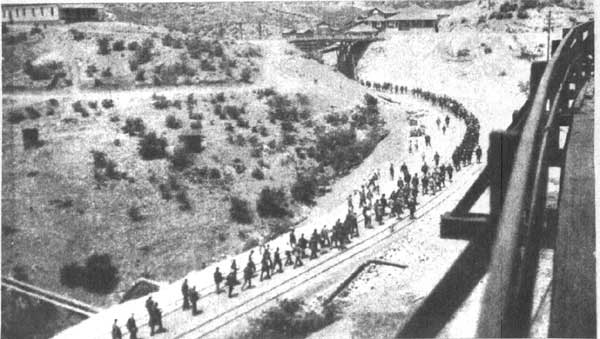

Cananea miners gathered in front of the police station as boss Greene fruitlessly tries to convince them

to return to work. Strike was joint effort of Mexican and U.S. workers. Photo:Fondo de Cultura Económica)

The following article is translated

from a supplement to El

Internacionalista published by our comrades of the Grupo

Internacionalista

in Mexico and distributed to miners in Cananea along with the

accompanying

article, “Mexican

Miners Strike for Safety, Against Anti-Worker Attacks.”

June 1, 2006 marked the

centenary of the copper mine strike at Cananea, in the northern Mexican

state

of Sonora (about 50 miles southwest of Douglas, Arizona). The

conglomerate that

now operates the mines, Grupo México, decided to celebrate the

event in its

usual way: it tried to prevent the commemoration by ordering the

workers to

carry out their usual tasks. Against this flagrant attack – a blatant

violation

of the collective contract, which designates the anniversary as a

holiday – the

militant miners of Latin America’s largest copper mine went on

strike. For almost

50 days, the miners of Cananea fought shoulder to shoulder with their

fellow

Sonoran workers in the mines of La Caridad, in Nacozari (roughly 55

miles

southeast of Cananea) and La Calera in Agua Prieta, Douglas’ neighbor

just

across the U.S.-Mexico border, and with the steel workers at the

SICARTSA-Las

Truchas mill in Lázaro Cárdenas, on the Pacific coast of

Michoacán state. There

two strikers were cut down by enemy fire in a pitched battle that threw

back a

military/police attempt to break the workers’ occupation of the biggest

steel

works in Latin America.

The SICARTSA steelworkers

won a resounding victory, with an 8 percent wage increase with back

pay, and

withdrawal of all charges against the strikers. The Cananea miners, on

the

other hand, abandoned by their national “union,” had to return to work

empty-handed. The very same National Union of Miners, Metalworkers and

Allied

Trades of the Mexican Republic (SNTMMSRM, by its Spanish initials),

even though

it was under government attack, stood by the laws of Mexico’s

corporatist labor

system. The SNTMMSRM threw in the towel when the Federal Arbitration

and

Mediation Board (JFCyA) rescinded its contract with Grupo

México. The

battle-hardened miners were forced to take down their red and black

strike

banners (the traditional symbol for a strike in Mexico) for one simple

reason: the

lack of a revolutionary class-struggle leadership. But today, in

2007, once

again the militant miners of Section 65 have not buckled after more

than 130

days on strike.

After the death of 65 coal

miners, buried alive at Pasta de Conchos in the state of Coahuila,

about 110

miles north-west of Laredo, Texas in February 2006, there was an

avalanche of

comparisons between the current conditions in the mines and those that

prevailed 100 years ago in Cananea (see “Asesinato capitalista en Pasta

de Conchos”, El Internacionalista/Edición México

No. 2,

August 2006). A century

later, the bosses’ abuse of the workers is as brutal as ever. At the

dawn of

the 20th century, the dishonest official statistics indicated mining as

the

riskiest job in Mexico. Today it remains the most dangerous of the 121

official

industrial classifications. The miners of Pasta de Conchos were victims

of

criminal neglect of the most elemental safety standards by the

management (the

same Grupo México) and by the state and federal governments, who

relied on the

complicity of the mine workers’ “union.”

It’s not just the terrible

working conditions in the mines that continue to claim workers’ lives.

As they

have for the past century, the ruling class opts for the “peace of the

grave.”

While in 2006 the government of Ulises Ruiz Ortiz and the Institutional

Revolutionary Party (PRI) in Oaxaca attacked striking teachers,

accusing them

of endangering the education of the children, resulting in the murder

of over

20 supporters of the Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca (APPO),

at the

same time the PRI governor of Sonora, Eduardo Bours, closed Cananea’s

schools

in an attempt to pressure the miners by denying their children

schooling.

José de la Cruz

Porfirio Diaz, the dictator who launched industrialization and opened

Mexico to foreign capital. Cananea strike was one of key events that

led to his overthrow in 1910, after almost 40 years in power.

José de la Cruz

Porfirio Diaz, the dictator who launched industrialization and opened

Mexico to foreign capital. Cananea strike was one of key events that

led to his overthrow in 1910, after almost 40 years in power.

Much has been written about

the saga of the Cananea miners in 1906. Along with the textile workers

strike at

Río Blanco of 1907, it has been incorporated into the liturgy of

the rebellion

against the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz1.

The schoolbooks describe these struggles as precursors of the Mexican

revolution of 1910-1917. Esteban Baca Calderón and Manuel

Diéguez, whom the

official history has raised up as the heroes of the miners’ cause, have

taken

their places in the iconography of the Revolution. The battle cry,

“Five pesos

and eight hours of work, ¡viva México!” that was

hurled at the offices

of the U.S. company that owned the mine at the time has become famous

as the

succinct expression of the revolution’s democratic nationalist program.

However, the miners of Cananea marched under red banners, and

contrary

to their petty-bourgeois ostensible spokesmen Baca Calderón and

Diéguez, the

true leaders of the mine workers were revolutionary syndicalists

from the

U.S. and Mexico who fought for international workers revolution.

Origin and Development

of

the 1906 Strike

As the historian Javier

Torres Parés notes in his book La revolución sin

frontera (UNAM, 1990),

“As it developed, the workers movement in Mexico established many links

with

the U.S. proletariat.” So much that “in the border areas ... they

managed to

build a single zone of workers mobilization.” At the beginning of the

20th century,

about half a million Mexicans lived in the U.S. southwest, where they

made up

the bulk of the railroad maintenance workers, coal and copper miners,

and

agricultural laborers. Torres Parés highlights the influence

that the socialists,

anarchists and revolutionary syndicalists of the Industrial Workers of

the

World (IWW) in the U.S. had on the Mexican Liberal Party (PLM). The

principal

leaders of this party, the brothers Ricardo and Enrique Flores

Magón, were in

exile in the United States, and maintained contact from St. Louis

particularly

with the leaders of the PLM in Cananea. In the mines, workers from the

U.S.,

many of whom sympathized with the IWW, made up a third of the 7,500

employees

of the Cananea Central Copper Company (CCCC). Already in 1902, ’03 and

’04,

skilled workers from the U.S. had launched a number of strikes in

Cananea.

Various liberal and

“progressive” journalists have noted certain similarities between the

events of

1906 and the miners’ struggles today. On the day after the massacre at

SICARTSA, Luis Hernández Navarro published an article, “Cananea,

once again” (La

Jornada, 21 April 2006). The columnist Miguel Ángel Granados

Chapa, for his

part, wrote: “The poor working conditions in the Cananea, Sonora copper

mine

produced, on 1 June 1906, a strike that was put down by fire and sword.

Today

the union struggle there challenges the government over trade-union

autonomy” (Reforma,

1 June 2006). Granados Chapa recalls the discrimination against Mexican

miners,

their exclusion from the better paying jobs, and how they were paid in

Mexican

pesos when almost all their expenses were in dollars, since Cananea

depended on

goods imported from Naco, Arizona. These facts led various radicals to

perceive

the “revolutionary potential of the miners’ unionism,” as Granados

Chapa puts

it, which is why the PLM led the brothers Flores Magón and

“various U.S.

radical groups” sent delegates to the region.

Among the miners there was

a particularly deep resentment of the arbitrary discipline they endured

from

the supervisors, which reflected the paternalist regime of the

company’s owner,

“Colonel” William C. Greene, a small-time Wall Street stock manipulator

who

made himself into a “copper baron” and who ruled the mining town as his

personal

fiefdom. Greene had built a Yankee enclave in the Sonoran desert: in

seven

years he not only acquired the mining rights, but took hold of the

local

economy with his company stores and the refining plant that he built,

as well

as the rail lines he controlled linking Cananea with Naco and Nogales

in

Arizona.

The traditional nationalist

interpretation of the Cananea strike is based, in large part, on the

memoir of

Esteban Barca Calderón, Study of the Yaqui War and Genesis

of the Strike at

Cananea (1980)2.

He

especially denounces the “racial hegemony throughout the company, on

our own

native soil, at the cost of our national interests, to the detriment of

the

Mexican worker and national pride and of the most elementary principles

of

justice and national rights.”

Miners marching on company offices to

present list of demands on 1 June 1906.

(Photo: Agustin Victor Casasola)

The justified hatred of the

racist treatment of and systematic discrimination against Mexican

workers by

the U.S. owner did play an important part in the strike. However, there

were

other factors that fed the revolt, such as the fear of losing their

jobs as a

result of mining concessions to independent contractors, and opposition

to the

Díaz dictatorship. Barca Calderón, who would later become

an officer in

Francisco Madero’s anti-reelectionist army3

and ended his life as a PRI senator, was a petty-bourgeois intellectual

who had

recently arrived in the area. There he met up with Manuel

Diéguez, a local

merchant. This pair petitioned to local authorities against the CCCC’s

trampling on “free trade.” The workers had other concerns, and although

the bosses

and their men treated all Mexicans like peons, the Mexican miners did

not see

all U.S.-born employees of the company as identical. Their class hatred

for the

abusive foremen mixed with their resentment over their national

oppression.

Nevertheless, they found strong allies among the U.S. miners with whom

they

worked in crews.

There are many sources on

the outbreak of the strike. Adolfo Gilly, in his book The Mexican

Revolution

(The New Press, 2006), relates how the miners “went out on strike

demanding the

removal of an overseer, a minimum wage of five pesos for eight

hours

work, respectful treatment, and that all positions be filled, given

equal

abilities, by 75 percent Mexicans and 25 percent foreigners. They put

forward

their demands in a manifesto in which they attacked the dictatorial

government

as an ally of the foreign bosses.” The development of the strike itself

and the

repression that followed is well known in its broad outlines. The

anthology

edited by Eugenia Meyer, La lucha obrera en Canaea 1906

(Instituto

Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 1980) gives a detailed

exposition of the

official version of the events.

According to this version,

the struggle was set off by the announcement on 31 May 1906 in the

Oversight

mine that the workforce would be cut and the workload for each miner

increased.

On the early morning hours of 1 June, the workers gathered in front of

the mine

offices and declared their strike over these issues. They sent for

Diéguez and

Baca Calderón to be their spokesmen to the company. Two thousand

miners marched

through the mines, workshops, foundry and refinery, joining the

movement en

masse. During the afternoon of June 1, the miners’ protest passed by

the

offices of the CCCC and commercial emporium, and proceeded to march

behind a

Mexican flag and a number of red flags on the lumber yard. There they

were

repelled by high pressure fire hoses and rifle shots, which killed one

worker.

Infuriated, the strikers set fire to the lumber yard, where two North

American

supervisors died.

When protesters returned to

the city hall, boss Greene tried to convince them to return to work,

but they

paid him no heed. Company men, particularly the Americans, opened fire

on the

crowd. From the roof of a hotel, marksmen shot indiscriminately at the

miners,

killing several. According to reports in the Tucson Citizen and

the Douglas

Daily Dispatch, “One of the leaders, who, according to all

eyewitness

accounts, carried a red flag, continued to incite the Mexicans....

[S]ome of

the more excited Americans opened fire and a general fusillade

resulted. The

flag-waving leader was hit by at least fifteen bullets” (from Herbert

O.

Brayer, “The Cananea Incident,” New Mexico Historical Review,

October

1938). Gunfire continued through the evening and all night, resulting

in over

20 Mexican workers dead.

Meanwhile, boss Greene

telegraphed the state governor, Rafael Izábal, requesting that

he come to

Cananea himself and send troops. Since the troops could not arrive for

two days

due to lack of a direct route, Greene also asked Washington and the

state of

Arizona for help. Some 275 Arizona Rangers were dispatched from the

mining

center of Bisbee, crossing the border at Naco early on June 2, where

the

Sonoran governor Izábal swore them in as “volunteers.” Their

commander, Captain

Rynning, was given the same rank as an officer in the Mexican army.

The American militia

arrived in Cananea by train later that morning, where Izábal

harangued the

rebellious miners, rejecting a wage increase and equal pay for Mexican

and U.S.

workers. Among his arguments, he mentioned that American prostitutes

cost more

than their Mexican counterparts. In fact, the government of Porfirio

Díaz had

decreed a maximum wage law. At the same time, Governor

Izábal threatened

to send all recalcitrant strikers to fight in the genocidal war he was

waging

against the Yaqui Indians. When speakers for the workers responded,

they were

imprisoned on the spot together with the strike leaders. That afternoon

the

paramilitary rural police, the rurales,

arrived and the Rangers withdrew. The next day a platoon of

100 Mexican Army soldiers arrived. The town was placed under military

occupation.

At one point there were up

to 100 miners in the Cananea jail. A number of the leaders were

prosecuted by

Izábal’s odious government and sentenced to 15 years in prison

at the notorious

island fortress of San Juan de Ulúa in Veracruz harbor. They

were only released

in 1911 after the fall of the Díaz regime. These events were

intimately linked

with the fate of Díaz’s regime, the development of international

capitalism and

the first imperialist world war. One month later, on 1 July 1906, the

Liberal

Party launched its platform, written by Ricardo Flores Magón, in

which he

called for an eight-hour working day, a wage increase to cover the

necessities

of life and an end to racial discrimination, demands which clearly

reflected

the struggle in Cananea. In 1907, the mine was temporarily closed due

to the

financial crash on Wall Street and the recession that followed in the

U.S.

Despite regaining his control over Cananea with the suppression of the

previous

year’s strike, Greene lost the mines to the great Anaconda Copper

Company. Also

in 1907 revolutionary workers struggles broke out in Río Blanco

and Orizaba,

Veracruz, led by militant supporters of the PLM, and in 1910 the

Mexican

Revolution began.

Armed Americans protect offices of Cananea

copper company, June 1906

Who Led the Strike at

Cananea?

In the literature on the

Cananea strike, while reproducing the same nationalist version of

events,

various authors do reveal a certain awareness of the presence of

different

political currents that influenced the struggle. Thus the historians’

collective at the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH)

remarks

about the two PLM clubs in the area: “Although their leaders ... did

not come

from the working class but were small businessmen, intellectuals and

white

collar workers, they were recognized as leaders of the workers when the

strike

broke out” (La lucha obrera en Cananea

1906). However, their account leaves aside the considerable international influence of

anarcho-syndicalism on the struggle. In fact, the formation of a second

nucleus

of the PLM in Cananea was due to certain differences between the local

partisans of magonismo. While the Union of Liberal Humanity

(Unión Liberal

Humanidad) led by Baca Calderón and Diéguez set itself

the task of organizing a

Miners Union of the United States of Mexico, they only managed to unite

a few

of the better-paid workers in Cananea. On the other hand, the Cananea

Liberal

Club (Club Liberal de Cananea) spread its influence in the mines of El

Ronquillo

and Mesa Grande.

This second club was led by

the lawyer Lázaro Gutiérrez de Lara and by Enrique

Bermúdez, who served as the

link with the PLM in St. Louis, Missouri and with the Western

Federation of

Miners in Douglas, Arizona. At that time the WFM followed a

revolutionary-syndicalist political line. Bermúdez had come to

the area in

November 1905 as a representative of the newspaper Regeneración

and got in touch with Baca Calderón and Diéguez. After

the celebration of Cinco de Mayo organized by the magonistas,

at which Gutiérrez Lara was the principal speaker, agitation

among the workers increased to the point that “a good number of the

U.S.

workers, besides sympathizing with the WFM, also agreed with the ideas

of the magonista militants” as Salvador

Hernández notes in his chapter, “Libertarian Times. Magonismo in

Mexico:

Cananea, Río Blanco and Baja California” in Volume 6 of the

series edited by

Pablo Gómez Casanova, La clase obrera en

la historia de México (Siglo XXI Editores, 1980). Police

surveillance of

Gutiérrez and Bermúdez was also stepped up.

From the reports of the

police spies it is clear that the principal leaders of the workers’

struggle in

Cananea were Gutiérrez Lara and Bermúdez, and that the

two had gone about

preparing for the strike at meetings “on Wednesday and Friday evenings”

throughout the entire month of May. Two days before the strike broke

out, the

manager of the mine got in touch with the colonel in command of the

treasury

police to warn about “the intention to ‘organize’ the company’s Mexican

workers

for the purpose of calling a strike for the same wages as the U.S.

workers” and

also with the political goal of “gaining control of the government.”

According

to Greene, he was given timely information by a fink that “that a

socialist

club had held three meetings at midnight on May 30 at midnight, at

which a

large jumber of agitators of socialistic tendencies were present; that

agitators of the Western Federation had been through the mines inciting

the Mexicans

and they had been furnishing money for the socialistic club at Cananea.

He also

gave us a couple of copies of the revolutionary circulars that had been

widely

distributed” (cited by Brayer in “The Cananea Incident”).

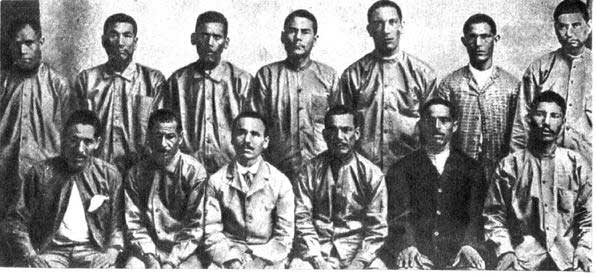

Some of the

Cananea miners arrested for participating in 1906 strike. (Photo:

Agustin Victor Casasola)

These facts alone refute

the validity of Baca Calderón’s version, according to which the

movement had

been “spontaneous.” So, asks Salvador Hernández, “Why this

distortion of the

facts, if Baca Calderón really was one of the workers’ leaders

present at the

meeting” that decided on the strike? It turns out that the decision

taken at

that meeting “caused a deep division among the members of the two main

workers

organizations in Cananea, over the methods of struggle to be followed

throughout the strike.” The group around Baca Calderón and

Diéguez, the Union

of Liberal Humanity, looked toward negotiation with the company and the

government,

which the others roundly rejected. Moreover, Diéguez “was

visibly upset,

condemning the movement.” On the morning the strike began, when the

workers

went to wake him, he didn’t want to go to management on behalf of the

strikers.

When Greene’s refusal to raise wages was received, “He told [the

workers] that

nothing had been gained. Having done this, Diéguez and

Calderón disassociated

themselves from the movement and withdrew to their homes.”

“For their part, the group

led by Gutiérrez de Lara, Enrique Bermúdez and a few

activists from the Western

Federation of Miners had opted for the road of direct action”, writes

the historian

Hernández. He cites an array of newspapers from the U.S. border

towns that put

the “blame” for the strike on the revolutionary agitators. “The problem

that

started the riot was prepared ... by incendiary speeches given by

members of

Mexican socialist organizations,” wrote the Tucson

Citizen of 2 June 1902, adding that “American socialist agitators

had come

to Cananea months in advance in order to propagate their doctrines

among the

Mexicans and spur them to the formation of miners’ unions.”*

The Douglas Daily Dispatch of 7 June

1902 reported, “With the arrival in Cananea some months back of Lara

and

Bermúdez, the current conflict began. These two men, by means of

revolutionary-spirited newspapers, began propounding the need to bring

down

Díaz’s government... and quietly began to organize revolutionary

workers’

clubs.”*

It is notable that in the

internal correspondence of the CCCC (cited in the book of Manuel

González

Ramírez, La huelga de Cananea [Fondo

de Cultúra Económica, 1956]), in a list of “agitators,”

who went about the

mines creating disturbances, nine Mexican workers are named and five

North

Americans (named Cunneham, Moore, Walsh, Woods and Kelley). In the

repression

that followed the defeat of the strike, both Gutiérrez de Lara

and Bermúdez

managed to escape to the U.S., where they were protected by their

comrades of

the IWW and the WFM. For their part, Diéguez and Baca

Calderón, in spite of

their decision to stay at home, and even though they thought “the

strike was

doomed to fail,” were sent to prison and later erroneously praised as

the

principal leaders of the strike. Calderón himself wrote that the

protagonists

of the action were “revolutionary groups that pursued ends of a

general,

national character” (Génesis de la huelga

de Cananea).

Ricardo Flores

Magón

Ricardo Flores

Magón

For the

revolutionaries who

in fact organized the strike, one cannot simply say that the strike was

a

disaster, despite its violent suppression. Ricardo Flores Magón

considered the

strike at Cananea an integral part of his plans for a social

revolution, which

were expressed in the program of the PLM, promulgated one month after

the

events of Cananea. However, the PLM was very far from being a party of

the

working class, much less of the proletarian vanguard. While the Flores

Magón

brothers did evolve toward anarchism, the roots of their party are to

be found

in Benito Juárez

and his 1857

Constitution, not in Marx or Bakunin. As Manuel González

Ramírez wrote in his

introductory note to the compilation of materials La

huelga de Cananea: “In their struggle, the liberal opponents of

General Díaz saw themselves as heirs to 19th century Mexican

liberalism. They

continuously put forward the paradigms of Benito Juárez4,

Ignacio

Ramírez5,

Melchor Ocampo6

and

Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada7.”

Revolutionary syndicalists

on both sides of the border were inspired by the Cananea uprising,

along with a

whole series of struggles led by the IWW “wobblies” and the WFM miners

in those

years. In 1911 and afterwards, as Torres Parés notes, they gave

rise to a

“mobilization with a clearly anti-imperialist tint that the workers of

both

countries waged against U.S. government intervention in Mexico.” The

1906

strike at Cananea was also a precursor of the copper miners’ strike of

1917 in

Bisbee, Arizona, that ended with the arrest and deportation of hundreds

of Mexican

miners (see “Bisbee, Arizona Deportation of 1917: ‘Reds’ and

Immigrants,” The Internationalist No. 2, April-May

1997). Nevertheless, the strikes of both Cananea and Bisbee

demonstrated the

inability of the doctrines of revolutionary syndicalism to complete the

longed-for

workers revolution.

To bring down the rule of

capital requires much more than for the workers to stop working. It

demands

that the most advanced elements of the working class place themselves

at the

head of all the oppressed, including the poor peasants and indigenous

peoples,

to prepare a general uprising that affects the bourgeois army, the

backbone of

the capitalist state. The active seizure of power must be prepared in

order to

build a workers state that can crush bourgeois reaction and open the

way to

socialism. The definitive act of a revolution is an insurrection, not a

general

strike. And for this a key element was missing, in 1906 as in

1910-1917: the

existence of a communist party of the working class vanguard, capable

of

carrying out the necessary preparations for victory that the militant

miners of

Mexico and the U.S. lacked. Without such a party, the Mexican working

class

will continue to be, in the famous phrase of José Revueltas, “a

headless

proletariat.”8

A Century of Workers

Struggle in the Sonora Desert

The workers struggle in

Cananea did not end at the beginning of the 20th century. Far from it.

As the

largest copper mine in Latin America and one of the ten largest in the

world,

the first industrial union was organized at Cananea in the 1930s, the

Grand

Workers Union of the Martyrs of 1906, which later became Section 65 of

the

SNTMMSRM. In 1971, the Mexican government bought up the majority of the

shares

of the Anaconda Copper Company and completed the nationalization of the

mine in

1982. With the investment of some $900 million to modernize its

physical plant,

Cananea greatly increased its output and became one of the most

important companies

in the country. Nevertheless, when the government of Carlos Salinas de

Gotari

decreed the privatization of over 1,000 state-owned enterprises, the

Cananea

mine was given to the Nafinsa development bank for reorganization (that

is,

reducing its workforce) to make it “more attractive” to buyers. In the

summer

of 1989, the management announced plans for closing two departments,

spinning

off other divisions to create new firms with new (and worse) labor

contracts,

and the firing of hundreds of the 4,000 workers.

The new companies were to

work 365 days per year, overriding the contracts that gave workers

Sundays and

holidays off. Section 65 went on strike. A week before the strike

began, the

mine was declared insolvent due to inability to pay its debts. But

around 80

percent of these were fictitious charges supposedly owed to Nafinsa. On

the

same day, thousands of Mexican army soldiers arrived in Cananea, who

proceeded

to pull 600 workers off the night shift, and barred 1,000 day shift

workers

from entering. Helicopters hovered over the city and troops patrolled

the

streets. The head of the SNTMMSRM, the corporatist “union” that was

part of the

PRI-government apparatus, asked for an audience with president Salinas

to

negotiate the matter.

But a rebellion was brewing

among the miners of Cananea. A resolution of Section 65 demanded the

withdrawal

of troops and the Federal Judicial Police, who were investigating the

union

“over the false impression that we had an arsenal and guerrilla groups.

We

don’t believe in the government or the PRI,” declared the motion. The

U.S.

expert on Mexican trade unions, Dan La Botz writes in his book, Mask of Democracy: Labor Suppression in

México Today (South End Press, 1992):

“Gómez Sada

declared that

the workers were not responsible for the bankruptcy of the company, but

took no

action to defend union members except to demand that they be severed as

provided by the contract and the labor law.”

Gómez Sada wasn’t alone in

abandoning the members of his own “union.” Neither the Confederation of

Mexican

Workers (CTM) nor the Congress of Labor (CT), the principal corporatist

labor

confederations, did a thing for them. The boss of the CTM and the CT,

Fidel

Velásquez, later said that he did not show any support for the

strike because

the SNTMMSRM opposed it (Andrea Becerril, “Impide Gómez Sada el

apoyo del CT a

obreros de Cananea”, La Jornada, 7

September 1989, cited in La Botz). The Mexican workers were dumbfounded

by the

utter capitulation of “their” unions.

After four days, the army

withdrew from the city. Even then, Gómez Sada insisted that

nothing could be

done, because everything had been done in accord with the labor law in

force.

The executive boards of Union Federation of Government Service Workers

(FSTSE)

and the Revolutionary Confederation of Workers and Peasants (CROC), an

alternative corporatist labor federation, expressed their

“understanding” for

the government’s actions. Despite the corporatist bureaucracy’s refusal

to take

up the least action in its defense, the miners of Section 65 went ahead

with

their strike plans. On 28 August 1989 they walked out, and on September

1 independent

unions demonstrated in the capitol in support of the workers of

Cananea. The

Labor Department proposed to withdraw the bankruptcy judgment in

exchange for

eliminating 115 clauses of the contract and amending 143 others,

definitive

proof of the spurious nature of the “bankruptcy.” A few days later, the

JFCyA

approved the company’s petition to void the contract in its entirety.

Napoleón

Gómez Urrutia,

leader of SNTMMSRM, fell afoul of PAN governments, whereupon he was

removed and criminal charges brought. Class-conscious workers demand

all charges be dropped while fighting in corporatist “unions” to form workers committees free of any

state control.

Napoleón

Gómez Urrutia,

leader of SNTMMSRM, fell afoul of PAN governments, whereupon he was

removed and criminal charges brought. Class-conscious workers demand

all charges be dropped while fighting in corporatist “unions” to form workers committees free of any

state control.

(Photo: El Porvenir)

Already at that time, the

differences between Section 65 and the national miners’ “union” had

come to

light, as well as the division in Cananea itself between the section’s

executive committee, which followed the directives of Gómez

Sada, and the

strike committee. The corporatist bureaucrats declared their readiness

to

accept voluntary resignations by the workers along with the severance

pay

proposed by the government. Nevertheless, the strike continued under

the direction

of the strike committee. Miners blockaded the federal highway and

occupied the

local offices of the JFCyA. Finally, the SNTMMSRM “negotiated” a new

contract

that eliminated more than150 clauses, reducing the number of job

descriptions

to three, laying off 400 workers and refusing to rehire over 700 more –

altogether

a third of the mine’s workforce – and a payment to the union in

exchange for

the layoffs. It is this payment, the famous $50 million, for which the

government is now going after the son and heir of Gómez Sada,

Napoleón Gómez Urrutia.

The reality is that from

the beginning, the government considered these funds not as a benefit

for the

laid-off workers, but as a bribe to the union for undermining the

struggle of

the Cananea miners. But like all bribes, this payoff to the corporatist

“union”

leaders for their complicity expired the moment that they demonstrated

the

slightest failure to cooperate with the regime. Thus, when Gómez

Urrutia

opposed the failed “Abascal Law” for labor reform, and then

characterized the

mine workers’ deaths in Pasta de Conchos as “industrial homicide” (a

declaration made to escape the wrath of families of the miners who

considered

the the “union” and the company “are one and the same”), the Fox

government

withdrew its support from Gómez Urrutia, accusing him of

misappropriation of

funds, and sought to impose another chief, Elías Morales

Hernández. As we explained

in our article “Asesinato capitalista en Pasta de Conchos”:

“When the regime

turns on

the ‘misbehaving child’ Gómez Urrutia to replace him with his

old rival Elías

Morales (who was second in command under Napoleón Gómez

I), it does so in order

to tighten the screws of its machinery and guarantee stricter control

over the

workers movement. Thus, it is vital for the workers to mobilize against

this

government attack and simultaneously take concrete measures to free

themselves

from all state tutelage. The workers themselves must be the ones to

smash the

corporatist apparatus by which they are tied to the capitalist state....

“In the

corporatist

‘unions’ workers committees must be formed to fight irreconcilably for

the

elimination of all state control, to break with the CT and organize

genuine

workers’ unions.”

In 1990 the mine was sold

to Grúpo México, headed by Jorge Larrea, a buddy of

president Salinas. Despite

the heavy defeat they suffered in 1989, the workers of Cananea slowly

recovered

their strength. In November of 1998 a new strike broke out, against the

company’s plans to lay off 700 of its 2,100 employees. The following

January,

the government declared the strike “nonexistent,” and threatened to

annul the

union’s legal charter. The company threatened to reopen the mine with

scab

labor. The leaders of the corporatist SNTMMSRM announced that they had

signed

an agreement to return to work, putting pressure on the local strike

leadership. But when the government representatives went back on their

offer of

an increased severance pay, the miners occupied the mine, where they

awaited

the onslaught of four Army convoys and over 300 paramilitary cops of

the Sonora

Judicial Police. Faced with the possibility of a deadly attack, they

finally

decided to abandon their occupation. Nevertheless, when they returned

to work

they found that 120 of their comrades who had been most active in the

strike

had been fired, and many others were given temporary contracts that

expired

every 28 days.

Cananea

miners with red-and-black strike

flag outside mine, December 1999. National labor leaders repeatedly

stabbed Cananea strikers in back. (Photo:

Milenio)

Cananea

miners with red-and-black strike

flag outside mine, December 1999. National labor leaders repeatedly

stabbed Cananea strikers in back. (Photo:

Milenio)

One of the most significant

aspects of the 1999 strike was the contribution from unions and copper

miners

north of the border. Shortly after the strike broke out, the strikers

sent a

delegation to Tuscon, Arizona. There, they received a warm welcome from

the

organizing office of the AFL-CIO. Although in the past the U.S. labor

federation has followed a protectionist program,

blaming Mexican workers for “stealing American jobs,” when the North

American

Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) came into effect in 1994, the job losses

were so

great that the AFL-CIO bureaucrats occasionally have decided to help

Mexican

workers fight for better conditions. Another factor in this case were

the many

miners in Arizona with relatives working in the Sonora mines.

Nevertheless,

U.S. unionists could see that ‘”the leaders of the Mexican miners

union” were

“more loyal to the government and the PRI than to their own striking

members”

(David Bacon, “Miners’ Strike Broken in Cananea”, Z

Magazine, May 1999).

The miners of Cananea were

betrayed time and again by “their” union leaders, who in reality are

functionaries and representatives of the capitalist state. In August

2006,

after the bitter experience of that year’s strike, they demanded that

the

national “union” not participate in their wage negotiations with Grupo

México.

Today, with the corporatist system in deep decay, thus opening a crack

in the

state’s retaining wall of corporatist unions that are integrated into

the PRI

and the state apparatus, the objective conditions are present for a

successful

struggle for trade-union independence from the control of the bourgeois

state

and the bosses. But as Leon Trotsky pointed out in his work, “Trade

Unions in

the Epoch of Imperialist Decay,” the fight for union independence and

union

democracy is inseparable from the struggle for a revolutionary

leadership.

Despite their combative

spirit displayed in their strikes of 1989, 1999 and again in 2006, the

miners

have not had a leadership equal to their needs, able to simultaneously

confront

the bosses, the capitalist state and its labor cops in the corporatist

unions.

Only a class-struggle leadership, united in a communist party composed

of professional

revolutionary cadres, would be able to take on this task. This decisive

element

was the contribution of the Russian Bolsheviks under V.I. Lenin, who

together

with Leon Trotsky led the October revolution of 1917, a few months

after the

Bisbee strike. And it is exactly the recognition of the urgency need to

forge a

revolutionary leadership that is the foremost lesson of a century of

internationalist class struggle in Cananea. ■

*Retranslated from

Spanish to English.

1 A

Liberal

(anti-clerical) military officer,

and later president of Mexico (officially, by repeated reelection, or

through

puppets) from 1876 until he was forced to resign and flee to France in

1911.

2 For a quarter century beginning in the 1880s the Díaz dictatorship waged a war to put down independence struggles of the Yaqui native people who inhabited the Sonoran desert.

3 Francisco Madero, who won the 1910 election, became president of Mexico when Díaz fell to the revolution. He led the moderate bourgeois Anti-Reelectionist Party, whose Plan of St. Louis called for modest land redistribution (on idle lands) and democratic reforms. Once in power, Madero unleashed the “Constitutionalist” army inherited from Díaz against radical peasant armies led by Francisco Villa and Emiliano Zapata.

4 Benito Juárez, a liberal jurist and Zapoteco Indian, was the first indigenous head of state in the Western hemisphere, holding office from 1858 to 1872. He helped write and implemented the laws known as La Reforma, curtailing the power of the Catholic church and the military, which led to war against clerical reactionaries (1858-61) and the Emperor Maximilian (1862-67), imposed by a French invasion at the invitation of Mexican conservatives.

5 Ignacio Ramírez, author of the book There Is No God, was minister of justice and public education under Juárez during the War of La Reforma against clerical domination.

6 Melchor Ocampo was a liberal intellectual who as minister of the interior under Juárez authored the Reform Laws separating church and state.

7 Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada was foreign minister under Juárez and president of Mexico from Juárez’ death in 1872 until 1876, when he was overthrown by Porfirio Díaz. .

8 José Revueltas, the Mexican author and film writer, was expelled from the Communist Party after 15 years membership, went on to found the Liga Leninista Espartaco and later showed sympathies for Trotskyism. His Ensayo sobre un proletariado sin cabeza (written in 1960-61) is an indictment of the failure of the Stalinized Communist Party to act as the vanguard of the Mexican working class.

See

also: Mexico: Cananea Must Not Stand Alone!

(1 February 2008)

New York Picket Protests Repression

Against Mexican Miners (11

January 2008)

Mexican

Miners Strike for Safety (15

December 2007)

To contact the Internationalist Group and the League for the Fourth International, send e-mail to: internationalistgroup@msn.com