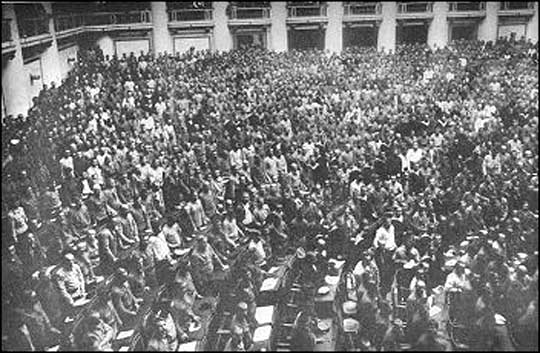

October 2007

Petrograd Soviet in 1917. For the Bolsheviks, the call for constituent assembly was a tactical

demand against anti-democratic regimes not an all-purpose slogan for all times. Trotskyists fight

for the program of the October Revolution, power to workers and peasants councils (soviets).

Over the last several years, calls for the establishment of a constituent assembly have been increasingly heard in various countries of Latin America. Most recently around the mass strike and quasi-uprising in Oaxaca, Mexico during May-November 2006, demands were raised by the Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca (APPO) and a host of left groups for a constituent assembly, a “revolutionary constituent assembly,” a “democratic and popular national constituent assembly,” etc. Although a constituent assembly elected by universal suffrage is no more than a bourgeois-democratic demand, it has been put forward by revolutionary communists in fighting against a variety of pre-capitalist and colonial regimes or bonapartist dictatorships. It was one of the key planks of V.I. Lenin’s Bolsheviks in tsarist Russia, in the 1905 Revolution for example, until it was superseded as the central demand by “all power to the soviets” in the course of 1917. Trotsky raised the call for a national assembly in China under the warlords, while emphasizing that it would only be part of a program for the taking of power by workers and peasants councils (soviets). But the current deluge of calls for a constituent assembly in ostensibly bourgeois-democratic regimes is counterposed to Bolshevism. It replaces the program of proletarian revolution with that of (capitalist) “democracy,” a hallmark of social democrats everywhere.

In

its various formulations, the slogan harks back to the 18th century

French

Revolution when the Third Estate (representing the rising bourgeois and

petty-bourgeois forces) formed a National Constituent Assembly in June

1789 to

sweep away the remains of the Old Regime (ancien régime),

of an

absolutist monarchy atop a decaying feudal social order. Their initial

aim was

to establish a constitutional monarchy to put an end to the chaotic

conditions

which impeded the growth of a national market, with power to be shared

between

the king and the assembly. But revolutionary events soon outstripped

the plans

of the bourgeois “moderates.” By 1792 the National Assembly had been

replaced

by the National Convention led by the Jacobins under Robespierre. With

the

further development of capitalism, the working class came to the

fore. By

the time of the June Days of the 1848 Revolution in France, the

National Assembly became

the

focal point of bourgeois reaction against the proletarian

uprising. In Germany and Austria as well, bourgeois

constituent

assemblies in Berlin, Vienna and Frankfurt in 1848 made their peace

with the

forces of reaction out of fear of workers revolution.

Generically,

a constituent assembly is not simply a parliament but a body which

would set up

(constitute) a state structure, for example, by issuing a constitution.

In

France, the second, third and fourth republics were all established by

constituent assemblies. In Latin America today, demands for such an

assembly

are typically accompanied by calls to “refound” the country. It can be

a key demand

in a country where whole sections of the population have been excluded

from

exercising democratic rights (for example, in Ecuador the large Indian

population was effectively disenfranchised until 1978 by requirements

that voters

be literate in Spanish). It is also appropriate where a feudal or

semi-feudal social structure prevents the vast mass of the rural

population

from any participation, with landless peasants tied to the landed

estates

through debt peonage, such as in Mexico prior to the 1910-17 Mexican

Revolution. In such cases demands for a “national convention” or

constituent

assembly to resolve the land question through agrarian revolution,

eliminate

clerical domination of education and carry out other democratic tasks

can be

powerful levers to rouse the masses to revolutionary action. The same

could be

true in the struggle to bring down military dictatorships, as held sway

in much

of Latin America in the 1970s.

Supporters

of Evo Morales march to defend Constituent Assembly, December 15. To

defeat right-wing reaction what is needed is revolutionary class mobilization, fighting for a

workers, peasants and Indian government. (Photo:

Juan Karita/AP)

Supporters

of Evo Morales march to defend Constituent Assembly, December 15. To

defeat right-wing reaction what is needed is revolutionary class mobilization, fighting for a

workers, peasants and Indian government. (Photo:

Juan Karita/AP)

But

to raise the call for a constituent assembly in Ecuador or Mexico

today, where

the formal structures of bourgeois democracy, however stunted, exist

and

semi-feudal latifundia have long-since been replaced by

capitalist agriculture,

would be to call to “refound” the country on a bourgeois basis

when what

is called for is socialist revolution. In Bolivia, the Movement

Toward

Socialism (MAS) of Evo Morales campaigned for a constituent assembly,

in order

to foster the illusion that it was calling for fundamental change while

not

touching the capitalist foundations of the country. This demand

was then

repeated by various left groups that tailed after the MAS, in an effort

to

pressure Morales to the left and pick up support among his plebeian

followers.

In the 2003 and 2005 worker-peasant uprisings that brought the country

to the

brink of insurrection, we noted that what was called for was not a

bourgeois-democratic constituent assembly (or even a left-sounding

“people’s

assembly”) but the formation of workers and peasants councils (soviets)

to

serve as the basis for a revolutionary worker/peasant/indigenous

government. We

also noted that while Bolivia was the continental champion in the

number of

coups d’état, it also led in the number of constituent

assemblies or congresses

(at least 19 by our count)1.

So Morales was elected in December 2005, and thereupon called the

constituent

assembly he had long promised. What was the result? Right-wing racists

have

hijacked the assembly to push their reactionary demands for regional

autonomy

from the Indian-dominated highlands (altiplano).

So

while in certain contexts it is appropriate for communists to call for

a constituent

assembly, this demand is by no means inherently

revolutionary-democratic. On

occasion, it can even serve as a cover for “democratic”

counterrevolution. Our

tendency, the League for the Fourth International (LFI), and the

International

Communist League/international Spartacist tendency (ICL/iSt) from which

we

originated, has had some experience with this issue. In an article,

“Why a

Revolutionary Constituent Assembly” (Workers Vanguard No. 221,

15

December 1978) we noted that when in Chile the Pinochet dictatorship

staged a

plebiscite and the Christian Democrats (DC) were talking of replacing

the

dictator with a reformed military junta, we denounced the rigged vote,

calling

for a revolutionary constituent assembly and to smash the junta through

workers

revolution. Our article, by the Organización Trotskista

Revolucionaria of

Chile, explained:

“Counterposed to

reformist

adaptations to the bourgeoisie’s program, as Trotskyists we raise the

demand

for a constituent assembly with full powers, directly and secretly

elected by

universal suffrage. A genuine constituent assembly by definition could

only be

convoked under conditions of full democratic liberties, permitting the

participation of all the parties of the working class. Thus it requires

as a

precondition the revolutionary overthrow of the junta, something which

the DC

and the reformists, despite their lengthy list of democratic demands,

fail to

mention.

“For Leninists,

democratic

demands are a subordinate part of the workers’ class program.

As Trotsky

wrote of the role of democratic demands in fascist-ruled

countries: ‘But

the formulas of democracy (freedom of the press, the right to unionize,

etc.)

mean for us only incidental or episodic slogans in the independent

movement of

the proletariat and not a democratic noose fastened to the neck of the

proletariat by the bourgeoisie’s agents (Spain)’ (Transitional

Program). In

countries with a bourgeois-democratic tradition and a politically

advanced

working class, such as Chile, the demand for a constituent assembly is

not a

fundamental part of the proletarian program. Thus following the junta

takeover,

the iSt did not raise this slogan. We raise it tactically at present

against

the bourgeoisie’s efforts, aided by their agents in the workers

movement, to

make a pact with sectors of the military. Our purpose is to expose the

bourgeoisie’s fear of revolutionary democracy.”

–“Condemn Pinochet

Plebiscite!” Workers Vanguard No. 190, 21 January 1978

In

contrast, on other occasions the call for a constituent assembly has

been

raised in order to head off the spectre of workers revolution. This was

the

case in Portugal in the summer of 1975. Following the fall of the

dictatorship

of Marcelo Caetano in April 1974, at a time when right-wing reaction

was

gathering around the sinister General Antônio Spínola, we

initially called for

immediate elections to a constituent assembly, as well as for the

formation of

workers councils. But a year later, as we pointed out in our 1978

article, “Why

a Revolutionary Constituent Assembly?” “workers commissions, popular

assemblies

and various other localized, embryonic forms of dual power were

springing up

everywhere around the country.” At that point, while the Portuguese

Communist

Party (PCP) was allied with leftist officers of the bourgeois Armed

Forces Movement

(MFA), with Spínola sidelined, counterrevolutionary forces

cohered around the

Socialist Party (PS) of Mário Soares, which with bourgeois

backing won the

April 1975 elections to a constituent assembly.

What

policy should revolutionary Marxists take? The largest ostensibly

Trotskyist

organization at the time, the United Secretariat of the Fourth

International

(USec), was split down the middle. The majority, followers of Ernest

Mandel,

hailed the “revolutionary officers” of the MFA, just as today many

would-be

radicals hail the bourgeois populist colonel Hugo Chávez in

Venezuela. The

minority, led by the U.S. Socialist Workers Party of Jack Barnes and

Argentine

pseudo- Trotskyist Nahuel Moreno, sided with the Socialists (heavily

financed by

the CIA via the German Social Democrats’ Friedrich-Ebert Stiftung) in

the name

of defending the “sovereignty” of the constituent assembly. So as

“socialist”-led

mobs were burning PCP offices, the USec was on both sides of the

barricades! In

contrast, authentic Trotskyists supported neither of the contending

bourgeois

coalitions, and called instead for the formation of workers soviets in

Portugal

counterposed to the rightist-dominated constituent assembly (see our

two-part

article, “Soviets and the Struggle for Workers Power in Portugal,” Workers

Vanguard Nos. 83 and 87, 24 October and 28 November 1975).

Member of

the Grupo Internacionalista/México (with microphone, left)

addressing

forum on democracy

called by the Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca (APPO), Mexico,

in August 2006. He said that

talk of democracy for the poor and working people under capitalism is

an illusion. What was needed

at height of struggle was to form workers and peasants councils

(soviets) to fight for workers revolution,

not a (bourgeois) democratic constituent assembly within capitalist

framework. (Photo:

El Internacionalista)

Returning

to the current situation, in September-November of 2006 articles

appeared in

radical

media around the world acclaiming a “Oaxaca Commune,” most of them

uncritical

enthusiasm, others adding a “left” twist by calling on this commune to

seize

power, expropriate the bourgeoisie, etc. How it was supposed to do this

in the

most impoverished, peasant-dominated state of Mexico was not explained.

Our

comrades of the Grupo Internacionalista in Mexico actively intervened

in Oaxaca

over the space of many months, but at the same time pointed out that

while a

number of unions were part of the Popular Assembly of the Peoples of

Oaxaca,

the APPO was not based on the working class or peasantry and thus was

not an

embryonic workers and peasants government – which is what the

Paris Commune

of 1871 or the Russian Soviets of 1917 were (see “A Oaxaca Commune?” in

The

Internationalist No. 25, January-February 2007). In fact, several

top

leaders of the APPO were supporters of the Party of the

bourgeois-nationalist

Democratic Revolution (PRD). The GI and LFI called for a national

strike against

repression and to break with the popular front around the PRD

and its

leader, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, and form a

revolutionary workers party.

Following

the bloody repression of 25 November 2006, the “far left’s” facile talk

of a

Oaxaca Commune has gone up in smoke, so today various radicals are

focusing

their calls on the demand for a constituent assembly. By far the

largest left group in Oaxaca is the Communist Party of Mexico

(Marxist-Leninist), which

writes that in order to achieve a “revolutionary democratic outcome,”

the left

must focus on “the discussion of a new constitution,” “achieving a

common

platform” and “placing in the strategy of the mass movement the

building of a

National Democratic and Popular Constituent Assembly” (Vanguardia

Proletaria,

5 March 2007). It’s not surprising that the PCM (m-l) should raise this

call, for it

is entirely in line with its reformist Stalinist program of a

“two-stage revolution”

and the popular front, and indeed, in the same issue an article praises

Stalin’s policies as “a classic of Marxism-Leninism.” But the

latter-day Stalinists

are not the only ones to defend this bourgeois-democratic line. Another

champion of the constituent assembly anywhere and everywhere is the

Liga de

Trabajadores por el Socialismo (LTS – Workers League for Socialism),

part of

the Trotskyist Faction (FT).

In

its balance sheet, “Crisis of the Regime and the Lessons of the Oaxaca

Commune”

(31 December 2006), the LTS writes that the APPO should have fought for

“a provisional

government that should call a Revolutionary Constituent Assembly.” More

specifically, APPO should have “transformed itself into a genuine organ

of

direct democracy of the exploited and oppressed, which would raise a

workers

and people’s program,” in order to “reorganize the state in the

interests of

the big majorities of the exploited and oppressed” and that a

“government of

the APPO and other working-class and popular organizations” as “an

expression

of the Commune” would “institute a genuine Revolutionary Constituent

Assembly”

in which the “working people, peasants and Indians, along with the

whole of the

people, could discuss how to reorganize society.” Just about everything

here is

contrary to Marxism. In the first place it is necessary not to

“reorganize the

state” but to smash the capitalist state and replace it with a workers

state.

Secondly, a genuine soviet is not simply an example of direct democracy

of the

poor, but a class organ of workers power. The LTS/FT

systematically

glosses over the working-class character of the program Trotskyists

fight for,

replacing it with mushy rhetoric about “democracy” and the “people” who

sit

around discussing what kind of society they want.

The

“democratist” rhetoric of this current is no accident, for it comes

straight

from the FT’s progenitor, Nahuel Moreno. The FT gets offended when we

call

them neo-Morenoite, as they claim to have broken with Moreno some years

after

his death in 1986. (See their “Polemic with the LIT and the Theoretical

Legacy

of Nahuel Moreno,” Estrategia Internacional No. 3, December

1993-January

1994.) But while objecting to various of Moreno’s most blatantly

opportunist

formulations, such as his call for a “democratic revolution,” the FT

keeps

his

methodological framework and many of his slogans. Thus the leading

section of

the FT, the Argentine PTS (Workers Party for Socialism) wrote following

the

December 2001 cacerolazos (pots and pans demonstrations)

against the

succession of bourgeois presidents:

“The slogan, ‘Get

rid of

them all!’ expresses the lack of legitimacy and the popular hatred

against the

regime of political representation…. But it still has not advanced to

identifying this regime, in its social content, with capitalist rule.

It is in

the sense of extending a bridge between the ‘democratic’ consciousness

of the

masses and the need for revolution and workers power that Marxists

raise the slogan

of a Revolutionary Constituent Assembly.”

–“The Constituent

Assembly

and Workers Power, a Debate on the Left,” La Verdad Obrera, 18

July 2002

Of

course, Trotsky himself presented the 1938 Transitional Program “to

help the

masses in the process of the daily struggle to find the bridge between

the

present demands and the socialist program of the revolution.” But what

the

PTS/FT does here is quite different, for the slogan of a constituent

assembly,

whether you label it revolutionary or not, does not by itself go beyond

the

limits of capitalism. In economically backward capitalist, semi-feudal

or

colonial countries, such an assembly could be the vehicle for mass

struggles

for agrarian revolution, national independence and basic democratic

rights. But

both before and after December 2001, Argentina was an independent,

fully

capitalist country which doesn’t even have a real peasantry but rather

agricultural

workers. To pretend that there is a “democratic revolution” to be

accomplished

in Argentina is to capitulate to and adopt the democratic illusions of

the

masses, not to lead them to socialist revolution. And that is exactly

what Moreno

did in making the call for a constituent assembly a centerpiece of his

program,

from Portugal (where he borrowed it from the U.S. SWP) to Argentina to

the

whole of Latin America.

Leon Trotsky arriving

in Petrograd in May 1917. Trotsky and Lenin fought for all power to the

soviets of workers, soldiers and peasant deputies.

Leon Trotsky arriving

in Petrograd in May 1917. Trotsky and Lenin fought for all power to the

soviets of workers, soldiers and peasant deputies.

The

cornerstone of Trotskyism is given in the first sentence of the

Transitional

Program: “The world political situation as a whole is chiefly

characterized by

a historical crisis of the leadership of the proletariat.” The purpose

and raison

d’être (reason for being) of the Fourth International, of

which this was

the founding document, was to provide that independent revolutionary

vanguard

to lead the struggles of the workers and oppressed to international

socialist

revolution. Moreno, however, rejected Trotsky’s view. In a 1980

document titled Actualización del Programa de

Transición

(Bringing the Transitional

Program Up to Date), he argued that “despite the defects of the subject

(i.e.,

that in some revolutions the proletariat was not the main protagonist)

and of

the subjective factor (the crisis of revolutionary leadership, the

weakness of

the Trotskyists), the world socialist revolution achieved important

victories,

expropriating the national and foreign exploiters in a number of

countries,

even though the leadership of the mass movement was still in the hands

of the

opportunist and counterrevolutionary apparatuses and leaderships.”

According

to Moreno, an independent Trotskyist leadership was not necessary to

carry out

what he called “February revolutions,” as opposed to October

Revolutions. He

then “updated” Trotsky’s program by postulating a whole stage of

February

Revolutions. In Thesis 26 of his article, Moreno wrote:

“Our parties must

recognize the existence of a pre-February revolutionary situation in

order to

come up with democratic slogans suitable for the existence of

petty-bourgeois

leaderships who control the mass movement and the need to establish

unity of

action as soon as possible in order to carry out a February revolution.

We must

understand that it is necessary to do so and not try to leap over this

stage,

but rather to draw all the necessary strategic and tactical

conclusions.”

So Moreno the

pseudo-Trotskyist is calling for putting forward democratic slogans

appropriate

for the petty-bourgeois leaderships, not a program for the

revolutionaries. And what might those slogans be? In Thesis 27, he

emphasizes

“the general democratic character of the contemporary February

Revolutions.”

Moreno goes on: “Hence the enormous importance acquired by the slogan

for a

Constituent Assembly or similar variants in almost all the countries in

the

world.” He refers to the constituent assembly as “the highest

expression of

democratic struggle,” saying that “we call for a constituent

assembly

while saying, ‘we are the biggest democrats’,” etc. He talks of

“developing

workers and people’s power,” whatever that means, saying that

ultimately the

objective is for the working class and its allies to take power. But

the bottom

line is that he is here putting forward a democratic program

for

petty-bourgeois (or even bourgeois) misleaders.

Moreno’s

1980 “updating” of the Transitional Program was part of a whole

evolution in

his political conceptions. Prior to that point, the Argentine

pseudo-Trotskyist

had distinguished himself primarily by his facility as a political

quick-change

artist, so much so that we referred to Nahuel Moreno as the Cantinflas

of the

Marxist movement, after his Mexican namesake, the comedian Mario

Moreno. The Argentine

Moreno was constantly trying to pass himself off as the left wing of

whatever

movement was in vogue at the time. After posing as a left-wing Peronist

in

Argentina, in the early 1960s he put on the olive green fatigues of

Castro/Guevera

guerrillaism. For a while in the mid-’60s, he enthused over the Maoist

Red

Guards in China. When some of his associates took him at his word and

actually

began to form a guerrilla front in Argentina in the late ’60s, with

disastrous

results, Moreno quickly backpedaled and put on the suit-and-tie of a

respectable social democrat, joining up with the remnants of the

Argentine

Socialist Party. In 1975-76 he was backing CIA-financed social

democracy in

Portugal. By the late ’70s, he was back to guerrillaism, this time as a

socialist

Sandinista. We documented this history in the Moreno Truth Kit

(1980)

first published by the international Spartacist tendency and now

available from

the League for the Fourth International.

Back

in Argentina, Moreno defended the bloody military dictatorship under

General

Videla against boycotts sparked by his European USec comrades, even as

the

junta was arresting and murdering Morenoite cadres. But by the early

1980s, the

junta was on its last legs, mortally wounded by its ill-fated military

adventure in the Falkland/Malvinas Islands (which the Morenoites loudly

hailed), and Moreno sided with the bourgeois Radical opposition led by

Raúl

Alfonsín, which took office after winning elections in 1983.

Moreno proclaimed

this A Triumphant Democratic Revolution in a book which bore

that title,

and thereupon invented a whole theory of “democratic revolutions.” The

programmatic

linchpin of this anti-Marxist dogma was his call, anywhere and

everywhere, for

a constituent assembly. This was Moreno’s final “contribution” to the

annals of

pseudo-Trotskyism. Genuine Trotskyists, in contrast, as we have

repeatedly

insisted, fight for international socialist revolution, led by

authentic

Leninist communist parties and based on worker and peasant councils,

i.e.,

soviets.

But

even before his infatuation with “February revolutions” (which came

around the

time Ronald Reagan was calling for a “democratic revolution” in Latin

America),

Nahuel Moreno was highlighting the call for constituent assemblies in

the

semi-colonial “Third World.” Thus in the mid-1970s, his publishing

house

(Editorial Pluma) put out a collection of Trotsky’s writings on La

segunda

revolución china covering the period from 1919 to 1938,

which prominently

featured the Bolshevik revolutionary’s call for a constituent assembly

around

1930, following the defeat of the second Chinese Revolution in 1927.

However,

this 220-page book left out all of the many articles by Trotsky

calling

for the formation of soviets in China, which was the focus of

his calls

for action by the Chinese Communist Party at the height of the

revolutionary

upheaval of 1925-27. Moreno’s skewed selection of documents was a

deliberate

distortion of Trotsky’s policies in semi-colonial countries. To this

day,

Spanish readers of Trotsky have never seen his repeated calls for

workers

revolution in China based on worker, peasant and soldiers soviets and

only know

the Morenoite bowdlerization.

Note

also that Moreno called for constituent assemblies not just in the

“Third

World” but rather “in almost all the countries of the world.” Including

the

imperialist “democracies”? How about in the United States? Indeed, the

short-lived

Morenoite organization in the U.S. called at one point in the early

1980s for a

constituent assembly. At the same time, they attacked our comrades with

claw

hammers – pro-capitalist “democratist” politics and anti-communist

thuggery go

hand in hand.

In

Bolivia, where the question of a constituent assembly has been a hot

issue due

to Evo Morales’ calls for one, a leading spokesman for the section of

the

Moreno-derived FT, Eduardo Molina, published an article at the outset

of the

2003 upheaval calling for a “Revolutionary Constituent Assembly” (Lucha

Obrera No. 11, 24 February 2003). In a section titled “Trotskyism

and the

Constituent Assembly,” Molina wrote:

“Leon Trotsky

raised the

demand for a National Assembly as a great banner to unify the masses

following

the Second Chinese Revolution, he put forward the slogan of a

Revolutionary

Constituent Cortes at the outset of the Spanish Revolution, in the

early 1930s;

and he demanded a national assembly, together with a program of

radical-democratic slogans against the regime of the French Republic in

his

Program of Action for France in 1934.”

This has been a

standard Morenoite argument for years, as they rewrite Trotsky in the

spirit of

bourgeois democracy. It has been more recently taken up by the French

Ligue Communiste

Révolutionnaire (LCR), the section of the United Secretariat, as

it becomes

ever-deeper incrusted in bourgeois parliamentarism. (The leaders of the

long-since reformist LCR have been trying for years to get rid of the

“C” and

the “R” in their name, but they keep running up against reluctance in

the

ranks.) LCR theoretician Francisco Sabado is now toying with calls for

a

constituent assembly in France, citing the same 1934 program as

justification

(“Quelques éléments clés sur la stratégie

révolutionnaire dans les pays

capitalistes avancés”, Cahiers Communistes No. 179,

March 2006).

Once

again, this is a distortion of Trotsky’s revolutionary politics. In

China, as

we have pointed out, Trotsky put the call for a constituent assembly in

the forefront

of his agitation following the defeat of the Second Chinese

Revolution,

where it was directed against the rule of warlords and the dictatorship

of

Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek; at the high point of the battle, his

central

call was for the formation of soviets. The Spanish Revolution

in 1931

was developing in struggle against the monarchy and the military

dictatorship

of General Primo de Rivera, which had ruled the country with an iron

hand since

1923. Trotsky’s call intersected pent-up demands for democratic

elections and

proclamation of a republic, for agrarian revolution, the separation of

church

and state and confiscation of church properties. Thus the demand of a

revolutionary constituent assembly or Cortes was the generalization of

a whole

series of democratic demands which were the portal to the socialist

revolution.

Of course, Trotsky combined this with propaganda for the formation of

soviets.

And by the time of the Spanish Civil War of 1936-39, the demand for a

constituent assembly was no longer appropriate under the Republic.

The

situation in France in the mid-1930s was very different, and Trotsky

did not

call for a constituent assembly there, contrary to Morenoite mythology.

So what

did his June 1934 “Program for Action in France” advocate? At the time,

right-wing reactionaries and fascists were pushing the country toward

an

authoritarian “strong state” regime, reflecting a general trend

throughout

Europe symbolized by Hitler’s seizure of power the year before and the

February

1934 defeat of an uprising of the Vienna workers by the

clerical-fascist

Dolfuss regime in Austria. Trotsky’s central slogan in the face of this

bonapartist threat was not for a bourgeois-democratic

constituent

assembly, as the Morenoites suggest, but rather “Down with the

Bourgeois ‘Authoritarian

State’! For Workers and Peasants Power!” As part of the fight for a

“workers

and peasants commune,” Trotsky vowed to defend bourgeois democracy

against fascist

and royalist attacks. In that context, he called for abolition of

various

anti-democratic aspects of the French Third Republic, including the

Senate,

elected by limited suffrage, and the presidency, a focal point for

militaristic

and reactionary forces, and proposed a “single assembly” that would

“combine

legislative and executive powers.” We raised these points in our recent

article, “France Turns Hard to the Right” (The Internationalist

No. 26,

June-July 2007). But this is quite distinct from calling for a

constituent

assembly in a country that already has a bourgeois-democratic regime,

however

tattered and threadbare.

In

laying out his program of permanent revolution in the

economically

backward capitalist countries, Trotsky emphasized: “The central task of

the

colonial and semi-colonial countries is the agrarian revolution,

i.e.,

liquidation of feudal heritages, and national independence,

i.e., the

overthrow of the imperialist yoke.” He emphasized that revolutionaries

cannot

merely “reject the democratic program; it is imperative that in the

struggle

the masses outgrow it. The slogan for a National (or Constituent)

Assembly

preserves its full force for such countries as China or India. This

slogan must

be indissolubly tied up with the problem of national liberation and

agrarian

reform.” Hence the slogan is not appropriate in an imperialist country,

or

where those tasks have already gone beyond the bourgeois-democratic

level. In

Mexico or Bolivia or Ecuador today, no democratic demand can break the

stranglehold of imperialism or of capitalist agribusiness – this can

only be

accomplished by workers revolution.

To

pretend that a “democratic revolution” is posed in Latin America or

Europe

today is to play into the hands of bourgeois reaction, just as Moreno

did in

adopting the Reaganite rhetoric in the 1980s, which was then turned

against the

Soviet Union. It’s not surprising that many of the pseudo-Trotskyists

joined in

the anti-Soviet chorus over Afghanistan and Poland at the beginning of

the

1980s and stood with the counterrevolutionary Boris Yeltsin in 1991, as

the

Morenoites and the United Secretariat did. And it is equally logical

that in

taking up the call for a constituent assembly in France today, LCR/USec

“theorist” François Sabado should hark back to Rosa Luxemburg’s

criticism of

the Bolsheviks who had dispersed the Constituent Assembly in Russia in

January

1918 as a focal point for opposition to Soviet rule. In her unfinished

manuscript, On the Russian Revolution, Luxemburg criticized

Trotsky’s

defense of this revolutionary measure (in his 1918 pamphlet From

October to

Brest-Litovsk) and wanted a new Constituent Assembly to be

elected

alongside the Soviets, in the name of “democracy.” This is exactly what

occurred a few months later following the German Revolution of

November

1918, when the National Constituent Assembly became the base for the

governing

Social Democrats in smashing the Congress of Workers and Soldiers

Councils

while murdering Luxemburg and her fellow communist leader Karl

Liebknecht2.

We stand instead with Lenin, whose December 1917 “Theses on the

Constituent

Assembly” are excerpted below.

What

was posed in Oaxaca in June-November 2006, in Bolivia in June 2005 and

September-October 2003, and in Argentina in December 2001 was not to

call for

bourgeois-democratic resolution of the crisis, synthesized in the

slogan of a

constituent assembly, but to explain to the masses (and the left) that

none of

the objectives of the struggle could be achieved without the formation

of

organs of working-class power, backed by the urban and rural poor,

hand-in-hand

with the fight to build authentic Trotskyist parties and a reforged

Fourth International

to lead the struggle for international socialist revolution. ■

1 In 1825, 1826, 1831, 1834, 1839, 1843, 1851, 1861, 1868, 1871, 1878, 1880, 1899, 1920, 1938, 1945, 1947, 1961, 1967. See Luis Antezana E., Práctica y teoría de la Asamblea Constituyente (2003).

2 It

should be noted

that Luxemburg never published On the Russian Revolution, nor

is it clear that she

intended to do so;

it remained an unfinished manuscript. It was first issued as a pamphlet

in 1922

by Paul Levi (in an incomplete and inaccurate version) after he had

split from

the Communist Party and returned to Social Democracy, and has been used

ever

since as a banner by all manner of anti-communists. Moreover, when the

issue of

a national assembly and/or workers councils was posed in Germany in

November-December 1918, Rosa the revolutionary came down squarely for a

government of workers councils against the bourgeois “democracy” of the

National Assembly.

|

V.

I. Lenin, “Theses on the Constituent Assembly” (Excerpts) 1.

The demand for the convocation of a Constituent Assembly was a

perfectly

legitimate part of the programme of revolutionary Social-Democracy,

because in

a bourgeois republic the Constituent Assembly represents the highest

form of

democracy and because, in setting up a Pre-parliament, the imperialist

republic

headed by Kerensky was preparing to rig the elections and violate

democracy in

a number of ways. 2.

While demanding the convocation of a Constituent Assembly,

revolutionary Social-Democracy

has ever since the beginning of the Revolution of 1917 repeatedly

emphasised

that a republic of Soviets is a higher form of democracy than the usual

bourgeois republic with a Constituent Assembly. 3.

For the transition from the bourgeois to the socialist system, for the

dictatorship of the proletariat, the Republic of Soviets (of Workers’,

Soldiers’ and Peasants’ Deputies) is not only a higher type of

democratic

institution (as compared with the usual bourgeois republic crowned by a

Constituent

Assembly), but is the only form capable of securing the most painless

transition to socialism…. 14.

… The course of events and the development of the class struggle in the

revolution have resulted in the slogan "All Power to the Constituent

Assembly!"—which disregards the gains of the workers’ and peasants’

revolution, which disregards Soviet power, which disregards the

decisions of

the Second All-Russia Congress of Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’

Deputies,

of the Second All-Russia Congress of Peasants’ Deputies, etc.—becoming

in fact

the slogan of the Cadets and the Kaledinites and of their helpers…. 16.

The result of all the above-mentioned circumstances taken together is

that the

Constituent Assembly, summoned on the basis of the election lists of

the

parties existing prior to the proletarian-peasant revolution under the

rule of

the bourgeoisie, must inevitably clash with the will and interests of

the

working and exploited classes which on October 25 began the socialist

revolution against the bourgeoisie. Naturally, the interests of this

revolution

stand higher than the formal rights of the Constituent Assembly…. 17.

Every direct or indirect attempt to consider the question of the

Constituent

Assembly from a formal, legal point of view, within the framework of

ordinary

bourgeois democracy and disregarding the class struggle and civil war,

would be

a betrayal of the proletariat’s cause, and the adoption of the

bourgeois

standpoint…. |

To contact the Internationalist Group and the League for the Fourth International, send e-mail to: internationalistgroup@msn.com