June 2005

El Alto and the “People’s Assembly”

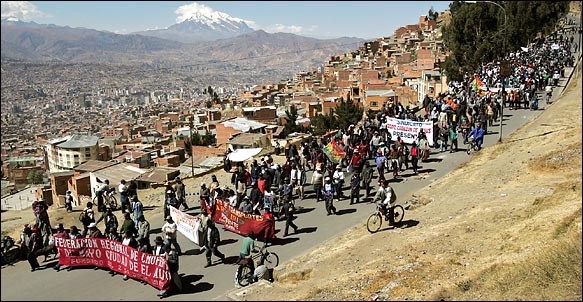

Bolivian mine

workers federation marches in La Paz, June 8. Miners are key sector of

Bolivian

proletariat. What is urgently required is to forge revolutionary

leadership. (Internationalist

photo)

The following eyewitness report deals with the National and

Indigenous

People’s Assembly (APNO) formed

by labor, peasant, Indian and slum dwellers’ organizations at the

height of the

mass demonstrations, strikes and road blockades that brought down

President

Carlos Mesa.

EL ALTO, Bolivia – The Asamblea Popular Nacional Originaria (APNO) met on the evening of June 10 in the headquarters of the El Alto Federation of Neighborhood Associations (Fejuve), a few blocks from La Ceja, where the road down to La Paz begins. The meeting took place the night after Supreme Court head Eduardo Rodríguez was sworn in as temporary president of Bolivia, at the end of a day when the entire country was convulsed by protests and troop movements (see “Bolivia Was ‘On Brink of Civil War’”).

On June 9, miners and

peasants effectively blocked the

attempt of rightist Senate head Hormando Vaca Díez to seize the

presidency. But

installing Chief Justice Rodríguez in the Palacio Quemado

presidential palace

is no victory for the workers, quite the contrary. Like his predecessor

Carlos

Mesa, the new president received backing from the armed forces, the

U.S.

embassy, and the most prominent “left” leader, Evo Morales of the

peasant-based

Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS – Movement Towards Socialism). Mesa

resigned 19

months after taking over from Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada, whose

massacre of El

Alto demonstrators failed to crush the upsurge of mass protest in the

October

2003 “gas war.”

The formation of the

People’s Assembly was hailed by quite

a few self-proclaimed socialist and would-be revolutionary groups as

the birth

of a new soviet-type body. Indeed, the resolution founding the assembly

on June

8 proclaimed El Alto the “general headquarters” of the Bolivian

Revolution. Yet

behind the rhetoric, the reality is quite different. The APNO is not a

centralizing organ of dual power, which doesn’t presently exist despite

the

considerable mass mobilization of recent days, but rather what we have

called

“a leadership cartel whose future evolution is uncertain.” In fact, the

June 10

meeting of the People’s Assembly, its third, was so far its last.

The APNO meeting took place right after plenary sessions were held of the Central Obrera Regional (COR – Regional Labor Federation), whose offices are next door, and the nation-wide labor federation, the COB (Bolivian Workers Federation). By the time the meetings were held, many road blockades were already dismantled throughout the country. In El Alto, buses and “micro” vans were running to and from La Paz. Pressure was building to end demonstrators’ blockade of the distribution of the tanks of liquid gas used for heating and cooking. With the help of the MAS, the Catholic Church and local authorities like the mayors of El Alto and La Paz, the ruling class and its media were pushing hard to demobilize protests.

Marchers

descend from El Alto into Bolivian capital of La Paz, June 8. (Photo:

AP)

I. The Fejuve, the

COR and the working class of El Alto

Before describing the meetings themselves, it is important to have a clear idea of El Alto’s social and political forces as reflected in the Asamblea Popular.

The international press often depicts El Alto as one huge slum. Certainly, the residents of Brazil’s favelas, the 2.5 million residents of Nezahualcóyotl outside Mexico City or the villas miseria of Lima and Santiago would recognize the widespread poverty here in the Andean altiplano. With many basic services lacking, raw sewage runs through central streets near La Ceja, while dogs prowl through huge piles of trash.

From El Alto’s inception, its population has had to fight for housing, transportation and education. A recent example was the bitter struggle to establish the Public University of El Alto (UPEA), whose students, faculty and workers have played a prominent role in the current protests, as they did in October 2003.

Racist discrimination is part of daily life for many alteños. Posh neighborhoods in the southern part of La Paz rely on this predominantly Aymara Indian city to provide maids, cooks and day laborers, treating them with ingrained racism and denouncing them as revoltosos (rebellious upstarts) when they protest.

These conditions have fueled a radical-plebeian outlook among broad strata of the population. Neighborhood associations (in both El Alto and in poorer sections of La Paz) display banners demanding nationalization of gas and oil, and denouncing “multinational” companies like the gas cartels and the French-owned Aguas de Illimani which sought to cash in on privatization of water. In mass demonstrations, the vecinos often chant that all members of Congress must resign or be kicked out.

Yet as the new president Rodríguez took office, the Fejuve, led by Abel Mamani, was increasingly divided. While denouncing Evo Morales’ “betrayal,” its spokesmen were actually following his lead. Together with the COR, it continued to issue radical statements at the same time as it prepared to seek new deals with the new president.

Contingent of Regional

Labor Federation (COR) marches in La Paz, May 31. Banner carries

slogan, “El Alto

Always on Its Feet, Never on Its Knees.”

Contingent of Regional

Labor Federation (COR) marches in La Paz, May 31. Banner carries

slogan, “El Alto

Always on Its Feet, Never on Its Knees.”

(Photo: Indymedia Bolivia)

The pattern for this was set by former COR leader Roberto De la Cruz in October 2003. De la Cruz was portrayed in the bourgeois media as a wild-eyed rabble rouser and lionized in the papers of various opportunist leftists. But the day after Carlos Mesa, vice president of the hated president Sánchez de Lozada (“Goni”), took over the presidency, de la Cruz met with him and agreed to a “truce,” defusing the October upheaval.

As we wrote then, De la Cruz and the other leaders sold out the workers and Indians (see “Bolivian Workers Uprising Knifed, Workers Still on Battle Footing,” The Internationalist No. 17, October-November 2003). This treachery became a stepping stone into bourgeois politics for De la Cruz: when his term as COR leader ended, he got elected to the El Alto city council as head of his own political party, M-17 (October 17th Movement). While the former COR leader is now widely derided as an opportunist, his successor Edgar Patana has shown that he is cut from the same cloth.

The populist politics of the Fejuve correspond to its social base: it is dominated by the gremiales, the small merchants who control retail business in this important commercial center. Importantly, this is also the case of the COR: the most vocal, numerous and influential section of the Regional Labor Federation of El Alto are the cuentapropistas (the self-employed), ranging from deeply impoverished street vendors to owners of small stores.

Tailing Fejuve leaders and middle-class intellectuals who theorize about a “democratic, non-class” answer to the centuries-old oppression of Bolivia’s Indian majority, many leftists speak in the name of “the people” in general. Some go so far as to claim there is “no working class” here. Not so.

El Alto is an

industrial city. By official figures it includes more than 5,000

industrial

enterprises, ranging from microempresas

(small workshops) to large gas, textile, leather, food, paper, cement

and

pharmaceutical plants. The COR itself includes a wide range of workers,

most

prominently the YPFB gas plant workers, butchers (El Alto processes

much of the

region’s meat) and other food workers, textile and

clothing workers, COTEL

and cell phone company employees, municipal employees, even unions of

shoe-shine boys and ice-cream vendors. In addition, several thousand

“relocated” miners live in the city, particularly in

the districts of Santiago

I, Santiago II and Ciudad

Satélite. Their association is affiliated to the COR, and they

played an

important role in the October 2003 uprising.

Then there are the workers who belong to the Federation of Factory Workers, much of whose leadership has historically supported the positions of the Bolivian Communist Party (PCB, the main Stalinist party) and which is affiliated to the COB national labor federation but not to the COR. The Federation’s members include the workers at the Coca-Cola and Pepsi-Cola bottling plants and the Pil milk products factory; Cementos Viacha and the Texturbol, Hilasa, Polar and other textile plants strung along the highway to Viacha; the Stege meat products plant, Vultexiber, Faderpa, Hilpaz and others on the highway to the mining town of Oruro. Just down the road in La Paz, the Federation includes the 1,500 employees of the Matex plant (which makes Polo brand clothing for the U.S. market), the workers of the Cervecería Nacional brewery, Vita and Inti pharmaceuticals, and many others.

Yet most of the alteño and paceño proletariat is not unionized, partly because of the infamous Decree 21060. This law, promulgated twenty years ago when Goni was a minister in the government of the withered nationalist caudillo Víctor Paz Estenssoro, is best known for closing the tin mines nationalized in the 1952 Bolivian Revolution, throwing the miners out of work and “relocating” them to places like El Alto. Decree 21060 also includes provisions (Article 55) giving “private enterprise” a free hand to fire workers for any kind of absenteeism – such as strikes.

Unlike the miners, factory workers had little organized presence in recent mass protests. Yet a revolutionary leadership would seize on the present period of upheaval to organize the unorganized, not only in trade unions (which often neglect the most vulnerable and super-exploited sectors) but in factory committees and workers councils. This cannot be accomplished by left and labor leaders who willfully dissolve the proletariat in the national-populist soup of “the people” in general.

As Lenin and Trotsky often stressed, the working class can win over the masses of impoverished and downtrodden non-proletarian sectors only if it puts forward its own class program and revolutionary leadership, providing a clear way out of the catastrophes caused by the capitalist system.

This was shown yet again in the Bolivian context when the Fejuve and COR blocked efforts to establish workers control of gas distribution. The proposal came from the Mine Workers Federation (FSTMB, the historic backbone of the Bolivian labor movement), which raised it in the newly formed Asamblea Popular, when the bourgeoisie was pushing hard to isolate El Alto and polarize La Paz residents, including in poor neighborhoods, against the mass protests blocking supplies to the city.

The FSTMB proposed to put miners, striking Senkata gas workers and neighborhood association representatives on trucks to control gas distribution to poor neighborhoods, hospitals and clinics, while choking off the flow to big companies and the bourgeoisie. This could have shown the power and organizing capacity of the working class acting in the interests of all the oppressed, as opposed to the venal and inept ruling class and government. If the miners’ proposal had been put into practice, this would have been a real element of dual power.

But it didn’t happen. The Fejuve and COR leaders covered their left flank with rhetoric provided especially by Bolivia’s supposedly Trotskyist organizations, claiming that the Asamblea was a “counter-government.” But at the same time, with their horizons limited to waging a strike and carrying our road blockades when what was needed was a struggle for working-class power, they stopped this concrete measure from going through, helping the bourgeoisie get out of the crisis.

Sabotaging the proposal for workers control of gas distribution was but a prelude to the “popular” leaders demobilizing the masses in order to help usher Eduardo Rodríguez into the presidency. Despite his milquetoast demeanor, it is no secret to anyone that this “Harvard Boy” is a sworn enemy of the workers, peasants and Indian peoples of this country, and a friend, lawyer and advisor to those (such as the U.S. embassy and the Goni mining concerns) who have oppressed and exploited them from time immemorial.

2.

The COR vows to

“continue the struggle”

The National and Indigenous People’s Assembly was founded by the COB (and chaired by COB head Jaime Solares), the COR and Fejuve of El Alto, the FSTMB miners union, the urban and rural teachers unions of La Paz department (province), the Tupac Katari-Bartolina Sisa Peasant Federation of La Paz department, students and unionists of the La Paz (UMSA) and El Alto (UPEA) universities, health workers, an association of the unemployed, and others. Numerically, it was dominated by the gremiales of the Fejuve and COR.

Edgar Patana, head of

the Regional Labor Federation (COR) of El Alto, speaking at People’s

Assembly meeting in El Alto. On right, Jaime Solares, head of the

national Bolivian Workers Federation (COB).

Edgar Patana, head of

the Regional Labor Federation (COR) of El Alto, speaking at People’s

Assembly meeting in El Alto. On right, Jaime Solares, head of the

national Bolivian Workers Federation (COB).

(Internationalist photo)

When we warned that the name “People’s” Assembly meant not proletarian in class character, supporters of ostensibly Marxist organizations here claimed this was a mere quibble over words. The course of events has shown that, far from being a semantic question, this was a political question, a class question, just as in the 1971 Asamblea Popular on which this APNO was explicitly modeled, which used “socialist theses” to package deadly illusions in the military populist General J.J. Torres.

Still more dangerous than the class-collaborationist “people’s power” rhetoric, as we have noted, Solares and a number of other COB and COR leaders had been using the language of populist nationalism (and anti-Chilean chauvinism) to appeal to military officers to form a “civilian-military government” (see box, “COB Leader Solares Sought ‘Civilian-Military’ Regime”).

On June 10 the El Alto COR met immediately before the People’s Assembly. The COR plenary was held in the small meeting room in the regional labor federation’s offices, packed to capacity with men and women gremiales as well as representatives of communications, construction and other workers. The meeting voted to “reject” the new president, saying Rodríguez coming to power changed nothing, noting his links to Goni and that he has been an advisor to the U.S. embassy. One worker said, “Que cambien el presidente a diario, no nos importa” (Let them switch presidents every day, it doesn’t matter to us).

The meeting voted to “declare Evo Morales and the MAS traitors to the workers struggle, who are only looking out for their own posts and to get money from the multinational oil companies.” Speakers denounced the “opportunism” of former COR head Roberto de la Cruz, who subsequently made a splash in the rightist daily La Razón saying “the people” were harmed by the El Alto protests.

Other COR resolutions called for Carlos Mesa and rightist congressional leaders Hormando Vaca Díez and Mario Cossío to be tried “for the murder of the miner compañero Juan Carlos Coro Mayta, a fighter for the nationalization of oil and gas”; denounced El Alto mayor José Luis Paredes – who had excoriated the protests as “savage” – as well as “the non-governmental organization Iniciativas Bolivianas, which uses resources from the U.S. cooperation agency USAID against the mobilizations of the alteños.” (USAID is a notorious CIA conduit.) Both Paredes and the “NGO” were given a 72-hour deadline to “leave the city of El Alto.”

The COR voted to consolidate “people’s power” and “support the Asamblea Popular Nacional Originaria, establishing a program, as well as committees of self-defense, supplies, press and a political committee, with the participation of delegates from the ranks of various social, trade-union, civic and patriotic organizations.” An amendment was incorporated “to warn that we will not accept as part of the leadership any traitors, opportunists or members of the neo-liberal parties” (such as those that backed Goni).

The very end of the COR meeting was devoted to reading and deliberating on a letter the newly installed President Eduardo Rodríguez sent to the COR, Fejuve and other organizations, asking them to meet with him in the presidential palace to discuss a “truce.” The meeting decided to decline the invitation to the palace but instead to invite Rodríguez to come up to El Alto to “see things for himself.” This laid the basis for the El Alto leaders to come to terms with the new president.

3. The National and

Indigenous People’s Assembly: “We are a government!”

The “APNO” met in a large hall on the ground floor of the Fejuve building. While a number of left and labor organizations were calling for the APNO to be based on elected and recallable delegates, the reality was that almost all those present were either there ex officio as leaders of their various organizations, or were self-appointed, or just showed up. Of the approximately 120-150 people attending the June 10 meeting, about half were peasants. The workers of the Senkata gas plant, who had been on strike and participated in previous APNO sessions, were not present.

Peasants at meeting of

National and Indigenous People’s Assembly in El

Alto, June 10.

Peasants at meeting of

National and Indigenous People’s Assembly in El

Alto, June 10.(Internationalist photo)

The session was opened by Jaime Solares of the COB, who said the main task was to consolidate the People’s Assembly. COR leader Edgar Patana reported on his federation’s decision to censure Evo Morales and the MAS for abandoning the struggle, and to continue the “intransigent and unbending” struggle for nationalization of gas and oil. He also reported the COR’s decision to accept President Rodríguez’s invitation to meet, with the condition that the discussion be held in El Alto.

Fejuve leader Abel Mamani gave the most openly “moderate” speech, saying in a slow and somber tone that the Fejuve had decided to continue the mobilizations, but “there is a lot of desánimo (low morale) among many members of neighborhood associations, some of which have lifted the blockades” without consulting the others. Mamani noted that a dangerous division had arisen between the population of La Paz and of El Alto, as the media and government pounded on the theme of hospitals and clinics going without gas; it was necessary to supply gas to hospitals and clinics or this would be used against the protesters. After three weeks of the strike and blockades, the neighborhood association members were “asking for a truce in order to resupply themselves.”

A representative of the peasants federation reported that a cabildo (open-air meeting of the citizens) earlier that day in the Plaza San Francisco in La Paz had voted not to retreat “even one millimeter” from the struggle for nationalization, that therefore road and highway blockades would not be lifted but strengthened, and the installation of a new president resolved nothing. Finally, he addressed himself to Fejuve leader Mamani, saying that “since we have already constituted this government which we have called the Asamblea Popular Originaria, we should begin to govern.” Yet despite the ringing proclamations, and the praise of the new “counter-government” from various centrist groups on the left, by the next day virtually all road blockades came down.

Representatives of the miners, La Paz teachers and UPEA talked of the need for concrete action, but they concentrated largely on technical-organizational measures trying to get supply, mobilization and defense and other commissions functioning. FSTMB leader Miguel Zubieta said his union and other affiliates of the COB “are in La Paz, awaiting instructions,” as were the departmental labor federations (CODs) that had been participating in blockades. The APNO had to form people’s assemblies in all of Bolivia’s nine departments or else it would be depicted as a kind of “El Alto autonomy,” parallel to the “autonomy” demanded by the Santa Cruz oligarchy, he added.

Zubieta called for commissions to be named on the spot, have people from specific organizations named to organize them, particularly the self-defense committees and a supply committee to deal with “how to distribute gas.” A speaker said “this is not just any strike in which we say ‘we’re going to blockade everywhere’.” Instead, “our Asamblea Popular Nacional Originaria should be the one distributing the gas, to the vecinos here, but it should be distributed by our committee, not by the mayor of La Paz or El Alto.” It was seen that this was a key question, yet lacking a Trotskyist revolutionary leadership, in a meeting dominated by labor and neighborhood association bureaucrats, the question was not posed clearly as the need for workers control of production and distribution. Instead, calls for concrete measures went unfulfilled, and the issue of gas distribution was used by leaders like Mamani to make a “truce” with the bourgeoisie.

The names of the various commissions were read out, and the organizations present called out which commissions they wanted to be part of. (A spokesman for the centrist LOR-CI called out that their “COB Youth Movement” wanted to be part of the Supply Commission.) Solares closed the meeting by raising the issue of how to respond to the letter of President Rodríguez. “We are a government! The letter should be addressed from one government to another,” someone shouted from the floor to applause and cheers. Solares said the response should be addressed from the APNO to “Dear President of the Ruling Class,” and ended by saying the decision should be that “nobody will go, nobody will go” to meet with Rodríguez.

4. The Aftermath

What happened over the next two days was something else entirely. On Saturday morning, the radio announced that a truce had been declared in El Alto for the weekend, and that gas would be distributed to hospitals and emergency centers. Beginning at 5 a.m. a line began forming outside the YPFB (state gas and oil company) distribution center at Senkata. But rather than distribution being carried out by the Senkata workers, miners and the APNO as had been proposed the night before, Fejuve leader Mamani met with a deputy minister in Rodríguez’s new government to coordinate distribution. As a result, the right-wing daily La Razón (12 June) reported: “A giant operation coordinated by the government, the police, the YPFB, the Superintendency of Hydrocarbons, the Association of Private Gas Distributors, and the mayors of La Paz and El Alto tried to open the way for the distribution of liquid gas and gasoline....” Police and soldiers rode on the trucks as they left the plants. A YPFB spokesman said that 60,000 tanks of liquid gas were filled, more than triple the usual daily amount.

The

bourgeois press crows about “breaking the

blockade.” Popular Assembly leaders sabotaged call for workers control

of distribution. Photo shows police supervising distribution of gas

cannisters.

The

bourgeois press crows about “breaking the

blockade.” Popular Assembly leaders sabotaged call for workers control

of distribution. Photo shows police supervising distribution of gas

cannisters.

Then on Sunday, the leaders of El Alto organizations met with the new “president of the ruling class” himself. On Monday, La Paz newspapers splashed photos of President Eduardo Rodríguez in El Alto shaking hands with the Fejuve’s Abel Mamani, together with leaders of the El Alto COR, the La Paz Peasants Federation – in other words, three of the four organizations on the platform at the Asamblea Popular on Friday night – as well as the Federation of Gremiales. “Rodríguez goes to El Alto and the Strike Dissipates,” the La Paz daily Jornada wrote in a front-page photo caption; “Rodríguez makes no promises but the alteños’ pressure ends,” it continued inside.

For his part, Mamani “announced the formation of commissions with people from the government and representatives of the El Alto social sectors to initiate a process aimed at having the agenda of the [Bolivian] Congress include the Constituent Assembly, nationalization of hydrocarbons and the call for general elections.” The COR’s Patana called the meeting purely “informative, with no result,” but added that the president plans early elections and that the population of El Alto will wait for him to name his cabinet in the hopes that it will “respond clearly to our demands.” As for the peasant federation’s vow to maintain blockades throughout the Department of La Paz, this too was a fiction.

So much for “nobody goes,”

not retreating “one

millimeter,” and the rest of the ringing promises and declarations made

at the

Asamblea Popular. The “APNO” served these leaders well to cover their

left

flank as they prepared yet another transa

(rotten deal) with yet another Goni successor.

Fejuve leader Abel

Mamani shakes hands with President Eduardo Rodríguez in El Alto,

June 12. Popular Assembly said “nobody will

go” to meet the “president of

the ruling class.” But sellout leaders went anyway.

Fejuve leader Abel

Mamani shakes hands with President Eduardo Rodríguez in El Alto,

June 12. Popular Assembly said “nobody will

go” to meet the “president of

the ruling class.” But sellout leaders went anyway.

On Tuesday, June 14, the gremiales from El Alto marched down to La Paz one more time. “We have formed the Asamblea Popular, like in 1971,” a soapboxer shouted through a megaphone on the Plaza San Francisco. “We need to take power, not through parliament or government officials, but through the organization of the workers and peasants, the Assembly of the People, the Popular Assembly like in 1971!” The speaker was part of a sales team hawking El Marginal, the El Alto publication of the Partido Obrero Revolucionario (POR), which for decades has claimed to be the sole repository of Trotskyism in Bolivia.

“Like in 1971”? This is indeed an old story, endlessly repeated by centrists who misuse the name of Trotskyism. The People’s Assembly paved the way for the bloody tragedy of 1971. As we have repeatedly emphasized, the real lesson of 1971 is that the nationalist, reformist and centrist leaders who came together in the Asamblea Popular used radical rhetoric to cover their actual support to the government of General J.J. Torres. That Assembly did not even meet for weeks before the coup led by rightist general Hugo Banzer in August 1971, after which they formed a “Revolutionary Anti-imperialist Front” (FRA) in exile with Torres et al.

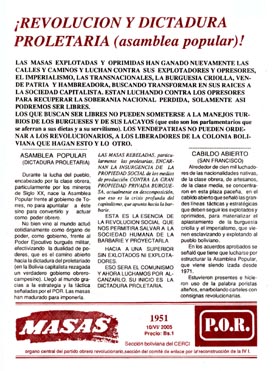

The POR has resuscitated its slogan of the FRA, which again features prominently in its central organ Masas. While Masas roundly denounces Evo Morales, scolds Fejuve and COR leaders, and the La Paz teachers later demanded Solares’ expulsion from the COB, Masas (No. 1951, 10 June) deliriously proclaims: “Proletarian Revolution and Dictatorship (Popular Assembly).” The La Paz teachers union issued a bulletin saying the Asamblea Popular “is an organ of the power of the people,” “becoming a real revolutionary government in embryo,” “a new organ of revolutionary power,” and so forth (Correo Sindical No. 8, undated).

POR’s Masas trumpets “Proletarian

Revolution and Dictatorship (People’s

Assembly)!” In contrast, League for the Fourth International told the

truth about stillborn APNO.

POR’s Masas trumpets “Proletarian

Revolution and Dictatorship (People’s

Assembly)!” In contrast, League for the Fourth International told the

truth about stillborn APNO.

The call to form a People’s Assembly “like in 1971” was repeated innumerable times not only by the POR but by the small centrist LOR-CI as well. On June 6 the LOR-CI issued a leaflet titled “Let’s form a bloc for the People’s Assembly!” This leaflet said “We believe the People’s Assembly could be built soon if the decision to convoke it is made by the COB, the CSUTCB (national peasants federation), the FSTMB, El Alto Fejuve and COR, the urban teachers federations of La Paz and El Alto and the rural teachers and other organizations of the workers, peasants, indigenous peoples and poor people in struggle.” For its part, the Movimiento Socialista de los Trabajadores (section of the International Workers League founded by Nahuel Moreno) assiduously tailed the labor bureaucracy, organizing student contingents to sing songs calling for a government of the COB (i.e., Solares).

So the assorted reformist, nationalist and populist misleaders did indeed form a People’s Assembly, and look at the result. To the sounds of dynamite blasts, today’s opportunists have helped organize what one militant aptly called a “pantomime” by bombastic leaders like Solares, populists like Mamani, COR leader Patana, etc. The POR’s Masas (No. 1952, 17 June) declared that the Rodríguez government is “stillborn.” At this point that is a more accurate description of the Asamblea Popular Nacional Originaria. To be sure, the POR et al. make ritual criticisms of the present misleaders of the masses and complain about the outcome. But what the whole range of opportunist left organizations did was “form a bloc” (as the LOR-CI urged) with these leaders, providing them left cover at the crucial moment, just when these leaders prepared to sell out the masses and make their deal with Rodríguez. The result has been yet another betrayal of the heroism and sacrifice of Bolivia’s workers and peasants, Indian peoples and urban poor.

Following the formation of the Asamblea Popular Nacional Originaria, the headline of the next issue of El Marginal (No. 13) was “What Is the People’s Assembly and What Will It Do?” An article declares that the APNO is “a true organ of power, though in these days nobody knows what they have created.” It goes on to say that “a powerful soviet has begun to be born and no one knows what it consists of, what its tasks are and what its scope may be.” The LOR-CI was a little less bombastic and more hesitant, but basically had the same line, referring to “an embryonic dual power arising in El Alto-La Paz” ( “Un ‘gobierno tapón’ que no cierra la crisis ni crea ilusiones entre las masas,” June 10). Covering their bets, the LOR-CI also referred to the APNO in a June 9 statement as a “First Step Toward a Popular Assembly.”

While the various pseudo-Trotskyists prettified the APNO as an “organ of power,” an embryonic dual power, a nascent soviet – even though “no one knows what it consists of, what its tasks are and what its scope may be” – the League for the Fourth International forthrightly told the truth. We wrote:

“Yet the incipient Popular Assembly, as presently constituted, is far from being an organ of dual power. It was called into being in a temporary ‘vacuum’ at the head of the government, while the capitalist state in the form of the army and police is still very much in place. For several leaders of the APNO, its proclamation was a fallback position, as in the case of COB leader Jaime Solares, who at key moments has been angling for a ‘civil-military’ regime with ‘patriotic’ military officers, or Fejuve leader Abel Mamani, who is seeking a national dialogue under the aegis of the Catholic church.

–“Bolivian Workers Move Against Threatened ‘Constitutional Coup’” (9 June)

None of those

tasks were carried out by the

APNO and its paper committees, and the immediate vital issue of workers

control

of distribution of gas was actually sabotaged by the action of

the El

Alto leaders. The key lesson to be drawn from the recent round of

struggle in

Bolivia is, once again, the need for revolutionary leadership. A

balance sheet

of the experience of Bolivia’s “Gas War I” and now “Gas War II” must

underscore

the urgency of establishing the nucleus of an authentic Trotskyist

party in

Bolivia. As opposed to the myriad groups who endlessly chase after the

latest

“new vanguard” or “nationalist in epaulettes,” a Bolshevik-Leninist

workers

party must be built on the program of permanent revolution,

in the fight to reforge

the Fourth International. With the

revolutionary leadership they deserve, as part of the international struggle of

the working class, the Bolivian workers and oppressed will win. n

|

COB Leader Solares Sought

“Civilian-Military” Regime

Just before the June 10 meeting of the People’s Assembly in El Alto, the COB labor federation had a plenary session of its leadership. The COB meeting passed a series of motions to continue mass mobilizations and the struggle for nationalization of oil and gas, resolutions which by the next day had become a dead letter. Between the sessions, El Internacionalista interviewed Jaime Solares, general secretary of the COB. Characteristically, as he did in the APNO meeting, Solares sprinkled his responses with rhetoric about “the great ideal of the workers and peasants government,” a “planned economy” and even the “dictatorship of the proletariat.” Asked about his calls for a “civilian-military government,” Solares said he had never called for a military coup, but “if there were a patriotic military government like that of Colonel Chávez in Venezuela, I would be the first to support it” because “it is a revolutionary government which leans towards socialism together with compañero Fidel Castro.” More concretely, Solares argued that when “the golpista [coup-making] general, compañero General Alfredo Ovando Candia, nationalized oil, the revolutionary comrade Marcelo Quiroga Santa Cruz was a minister in [the government of] this golpista general, so let’s not be naive....” After coming to power in a coup in September 1969, Ovando nationalized Gulf Oil, which controlled most of the country’s petroleum; Quiroga was an aristocratic intellectual who went from the fascistic FSB (Bolivian Socialist Falange) to a left-nationalist position, later founded the Socialist Party and was assassinated by paramilitary forces in the military coup of 1980. But the regime of the “compañero golpista general” was no friend of the workers. Ovando was chief of the military under the dictatorship of General René Barrientos, responsible for slaughtering the guerrilla band of Che Guevara in October 1967 and for ordering the massacre at the Siglo XX mine in Catavi on the night of San Juan in June 1967 when at least 87 people were killed, including many women and children. Under Ovando’s rule, the military wiped out the leftist band led by “Chato” Peredo. In July 1970, this group launched a guerrilla struggle near the mining community of Teoponte, a battle that was doomed to failure even more than Guevara’s debacle at Ñancahuazú. Despite Ovando’s personal guarantee, those who surrendered were executed on the spot. The next month, a fascistic band of gunmen paid and armed by Alfredo Candia, local chief of the World Anti-Communist League, brutally assaulted and occupied San Andrés University (UMSA) in La Paz with the tolerance of the army, resulting in a score of casualties. Solares praises the nationalist unity of “leftists” with the likes of Ovando. “To achieve power,” Solares cynically remarked in the interview, “the workers must use all means, as the great thinker Machiavelli said”! When challenged on his appeals to anti-Chilean chauvinism, Solares responded that “we are not against the Chilean people and workers” – “as Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara said, for good men there are no borders” – but what the Chilean workers should do is “fight for the Bolivians’ demand for a sea coast, so we can have a port.... The day this happens, then we can talk about a real Latin American unity of the workers.” (The demand for return of “Bolivia’s outlet to the sea,” which it lost to Chile in the War of the Pacific in the late 19th century, has long served as a battle cry for nationalist politicians, whether civilian or military.) In the 2003 Bolivian uprising, there was ample opportunity for real solidarity with Chilean workers, who carried out a general strike only days before. With regard to the APNO, Solares said the Asamblea Popular “is the government of the people, all that remains is to take power, in order to establish socialism in this country, but a totally Bolivian socialism.” A number of left tendencies refer to the COB secretary as “el loco Solares.” His statements may be erratic, but they are not accidental. They reflect the nationalist-populist political line pushed for decades by the dominant forces in the labor bureaucracy going back to Juan Lechín, the COB founder who, while leading miners militias, joined the bourgeois nationalist government in 1952, co-signed the decree to reestablish the army in 1957, and was up to his neck in the conspiracies with military officers that led to the 1964 Barrientos coup. Nor were Solares’ calls for a “civilian-military government” empty words. The COB chief did his utmost to bring about such a repeat of the nationalist military regimes of Ovando or that other “compañero golpista general,” Juan José Torres (who took over when Ovando fell in October 1970). Just weeks ago, on June 1, Pedro Cruz, “permanent secretary” of the COB, went so far as to hold a small rally at the entrance to the Estado Mayor (general staff) offices in Miraflores calling for a civilian-military regime. No “patriotic officers” answered the door. Several days after the June 10 COB and APNO meetings, the La Paz teachers union, whose leaders support the line of the Bolivian POR, demanded that Solares and Cruz be expelled from the COB for “encouraging military coup movements.” Yet Solares is the head of the Asamblea Popular, which the POR called on the leaders of the COB, among others, to establish. For the reformist/nationalist leaders, the Assembly was a platform to make radical-sounding speeches, denouncing the “betrayal” of Evo Morales and vowing to hold firm. The real political effect was for Bolivia’s left organizations to assist the leaders of the COB, COR and Fejuve to put on a left face while these leaders followed Morales in helping the latest interim president, Eduardo Rodríguez, defuse the crisis. |

To contact the Internationalist Group and the League for the Fourth International, send e-mail to: internationalistgroup@msn.com