November 2006

The

discrimination against and exclusion of the indigenous population is

one of the

fundamental causes of the Oaxaca rebellion. No one can ignore it in the

land of

Benito Juárez, the Zapotec Indian who became president of Mexico

in 1858 and

led the War of the Reform against church power and the resistance to

the empire

of Maximilian1.

The Popular

Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca (APPO) recognized this in the

resolutions of

the forum on “governability” which it called in mid-August.

However,

the Indian question is not limited to the legal framework or democratic

rights,

nor to the removal of this or that cacique (political boss), or

even the

whole cacique system promoted by the PRI (Institutional

Revolutionary

Party). To liberate the descendents of the original inhabitants from

the weight

of half a millenium of plundering, superexploitation and even genocide,

both

under colonial rule and the republic, will take a social revolution.

Only the

taking of power by the Mexican working class will make it possible to

shatter

the power of a bourgeois and even oligarchic ruling class in states

like

Oaxaca, where their fabulous riches are extracted from the sweat of

indigenous

working people.

The criollo

(European-derived) caste which rules Oaxaca is extremely

tight-knit: its

members see each other in sumptuous feasts held in luxury hotels and

the

exquisite restaurants which abound in this colonial city; they visit

each

other’s estates to admire the prize bulls and purebred horses. The

political bosses

maintain gangs of gunmen and thugs commanded by corrupt deputies and

congressmen to assassinate rebellious teachers. The oligarchs

flamboyantly

wheel around town in their latest-model SUVs with oversized tires and

polarized

windows – known as “garcmobiles” during the El Salvador civil war of

the 1980s

– from which demoiselles in party dresses alight to attend their

elegant

fiestas. Their offspring practice endogamy, marrying only within the

caste, and

they all display openly racist contempt for those with dark skin.

These

are the “powers that be” who lord it over the state of Oaxaca, and they

were

the ones who came out on November 1 in a PRI march to support Governor

Ulises

Ruiz Ortiz. They wanted a “cleaned-up” city, some ladies told an

American

reporter, claiming that a majority of the “appos” are from Chiapas or

Guatemala

(i.e., they are Indian “foreigners”) and that the leader of teachers

union Section

22 is a muxe (transvestite). The reporter, James Daria, noted

the “deep

seated economic and racial conflicts underlying the current social

unrest” (Narco

News Bulletin, 1 November). The deepest of these is the Indian

question.

“We

have already been warned … they already have their cuernos [de

chivo,

goat’s horn, nickname for AK-47 automatic rifles) ready for when the

damn

Indians of the APPO show up,” remarked a rich cattleman of the lower

Mixe

region, according to Carlos Beas Torres, a leader of the UCIZONI

indigenous

organization (La Jornada, 16 October). The striking teachers

have raised

among their demands defense of bilingual education against budget cuts

which

have hit hard against instruction in Indian languages. Meanwhile,

PRI-linked

paramilitaries have made death threats against the coordinators of

radio Huave

(the most powerful community radio station in the Isthmus of

Tehuantepec),

Radio Ayuuk and Radio Umalalang.

This “other war” against the indigenous

peoples is not

limited to threats: in early August when a delegation of a Triqui

Indian

organization, MULTI (Movimiento de Unificación y Lucha Triqui

Independiente),

set off to reinforce the teachers’ encampment in the Oaxacan capital,

they fell

into an ambush which left three Triqui Indians dead (Andrés

Santiago Cruz,

Pedro Martínez Martínez and the youth Octavio

Martínez Martínez) and four wounded.

And on October 18, a teacher of bilingual primary school,

Pánfilo Hernández of

Zimatlán, was murdered as he left an APPO meeting.

Nor

is this war new. The Triquis, ensconced in the Mixtec region of western

Oaxaca,

have been the target of constant aggression by the state and federal

governments in support of PRI caciques, leading to the murder

of many

fighters for Indian rights going back to the 1970s. Among those killed

are

Guadalupe Flores Villanueva, Luis Flores García, Nicolás

López Pérez, Eduardo

González Santiago, Efrrén Zanabriga Eufrasio, Pedro

Ramírez, Javier Santiago

Ojeda, Paulino Martínez Delia and Bonifacio Martínez.

Another of the murdered

activists in previous years was Bartolomé Chávez of the

CIPO (Popular Indian

Congress of Oaxaca).

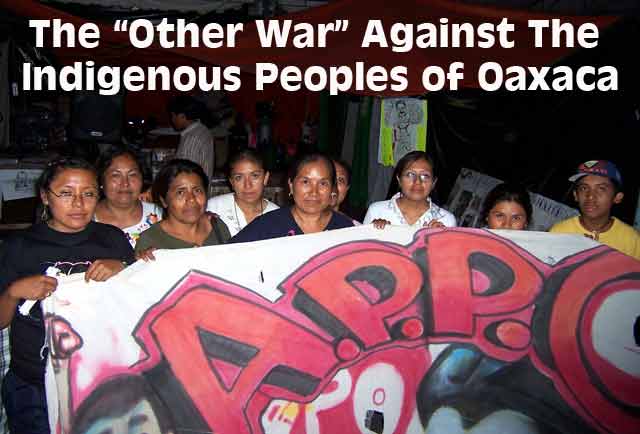

Banner of

the MULTI in the Oaxaca Zócalo, August 2006.

Banner of

the MULTI in the Oaxaca Zócalo, August 2006.

(Photo: El Internacionalista)

With

1.6 million Indians, more than half the total population, Oaxaca is the

state

with the highest percentage of the population who speak indigenous

languages

(37 percent, compared to 24 percent in Chiapas), including Zapoteco,

Mixteco,

Mazateco, Chinanteco, Mixe, Triqui and ten additional ethnic groups. Of

the 570

municipalities in the state, 412 are governed according to indigenous

“usages

and customs,” under which municipal posts are determined by a rotating

series

of positions or obligations (cargos) and general assemblies make

decisions by consensus.

Although

they are less corrupt than many other local governments, one doesn’t

have to

idealize the traditional indigenous governments. There are also PRI

Indian caciques,

and in a significant number of Indian communities (around 20 percent),

even in

the late 1990s, women didn’t have the right to vote. There is also

little

presence of women in the leadership bodies of Section 22, even though

women

make up a clear majority of Oaxacan teachers.

The centrality of

the oppression of

indigenous peoples in the present struggle in Oaxaca is widely

recognized. In

the APPO forum, resolutions called for a new state constitution to

include

“juridical recognition of the original peoples and their rights, among

them the

use of indigenous languages and acceptance of the accords of San

Andrés Larráinzar.”

However, neither legal recognition nor the autonomy codified in the San

Andrés

accords, negotiated with the Zapatista Army of National Liberation

(EZLN) after

the Chiapas rebellion of 1994, offer a solution to the profound social

oppression of the indigenous peoples. This oppression is rooted in capitalism.

Just

to cite some indicative figures: the areas of Oaxaca populated by

Indian

peoples are the most backward in terms of education and in the state as

a

whole, 27 percent of women are illiterate while 34 percent of primary

school

age children do not attend school. The poverty is enormous: 70 percent

of the

Oaxaca population earns less than 70 pesos (US$6.50) a day. 55 percent

of homes

lack sewage connections or any drainage, while 40 percent of the houses

have

dirt floors, according to statistics of the INEGI (National Institute

of

Geography and Statistics) based on the 2000 census. Currently, poor

Indians

feel particularly threatened by the Plan Puebla-Panamá, which

has led to

massive buying up of Indian lands by speculators who want to grab a

corridor

alongside the superhighway.

We

have written extensively about the struggle against the oppression of

indigenous peoples in Latin America, calling in several Andean

countries for a

workers, peasants and Indian government (“see Marxism and the Indian

Question

in Ecuador,” The Internationalist No. 17, October-November

2003). This

demand would also be appropriate at the state level in Oaxaca. In

Mexico as a

whole, where the weight of the Indian population is substantially less,

the demands

of the EZLN and the Indigenous National Congress (CNI) center on

indigenous

autonomy, as laid out in the San Andrés accords which were

turned down by the

National Congress (with the connivance, it should be noted, of the

PRD). As we

wrote concerning Chiapas:

“Marxists support the right

of the native peoples to decide their own fate. For the areas where

Indians are

concentrated, we join in demanding the right of regional and local

autonomy.

For this to have any reality, it must include control over natural

resources,

including land, water and petroleum. This will be strenuously resisted

by

Mexico’s capitalist rulers, as the state of Chiapas, where the Mayan

Indians

live in pervasive poverty, produces 21 percent of the country’s oil

output, 47

percent of its natural gas, and 55-60 percent of total electrical

production,

mainly from hydroelectric stations….

“Effective autonomy for

indigenous peoples will only be possible through socialist revolution

instituting a planned economy.”

–“Mexico: Regime in Crisis,”

Part 2, The Internationalist No. 2, April-May 1997

Oaxaca

does not have huge natural resources like Chiapas, but there is another

reason

why genuine regional autonomy cannot be realized within a bourgeois

framework.

The peasant Indian economy is deeply threatened by the capitalist

market, which

is the ultimate cause of the poverty in which the indigenous peoples

live. This

has been the case since the triumph of capitalism in the Mexican

countryside in

the last half of the 19th century, but its effects have been

accentuated in the

last decade by the Free Trade Agreement with the United States, which

has led

to the importing of massive quantities of corn and the ruin of Oaxaca’s

peasant

agriculture.

Despite

its rhetorical identification with the Mexican Revolution, the PRI

arose from

the layer of Northern ranchers (Obregón, Carranza) who were

responsible for the

assassination of Emiliano Zapata and Francisco Villa and the defeat of

the poor

and landless peasants. The same ranchers are still in power in Oaxaca,

and

following their class interests they identify with the hacienda owner

from Guanajuato,

President Fox. Expropriating their estates will be one of the first

steps of

any social revolution.

Yet

not even Zapata’s old program of “land to the tiller” will be

sufficient to

deal with this. Almost half of the cultivated land in Oaxaca is under a

communal regime, another quarter is in the ejido2

system, with little more than a quarter held as private property. Even

with

collective cultivation of the land, the urgently needed agrarian

revolution

in the Mexican countryside requires the industrialization of

agricultural

production, which will only be carried out to the benefit of the

indigenous

peasants in the framework of a socialized economy.

It

is also essential to break with all the bourgeois parties. The most

important

struggle of the Oaxacan Indians in the past was that of the COCEI

(Worker-Peasant-Student Coalition of the Isthmus) centered on

Juchitán, dating

from the mid-1970s. For a time, the COCEI was allied with the Mexican

Communist

Party, and COCEI members were always treated as communists by the PRI caciques.

With the dissolution of the remnants of the CP into the Party of the

Democratic

Revolution, the COCEI also joined the PRD.

After

many years of mobilization, the COCEI achieved power locally. However,

as

members of a capitalist party, the Juchitán COCEI/PRDers have

aligned with the

rulers of the state and played a markedly conservative role – to the

point that

in the current struggle, a significant number of teachers in

Juchitán broke the

strike. It is notable that the only place in the state where there was

a

significant amount of scabbing was precisely in this stronghold of the

PRD.

The

struggle to defend the original peoples is also not identical to zapatismo,

although the appearance of the EZLN in 1994 did attract a great deal of

attention to the conditions of Indians in Mexico. The political support

which

the EZLN gave for many years to the PRD didn’t help indigenous peoples

in

Chiapas or the rest of the country, as Subcomandante Marcos himself

admitted in

his June 2005 Sixth Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle.

In

August 2005, a meeting was held in a Zapatista community bringing

together

indigenous representatives from all over Mexico. Spokesmen for the CIPO

complained:

“It

saddens us to see that the EZLN says something when something happens

to those

who are well-known, yet when blows are struck against communities,

organizations

and persons who are small, simple and little-known, they say nothing.

“We

perceive a differential treatment by the EZLN, which on the hand gives

priority

to its ties to the world of the NGOs3

and organizations who carry out little or no work with the ranks, while

it

leaves aside the rank-and-file indigenous movement, which actually goes

out

into the streets and fights alongside us.”

It is no accident, then, that during the

current

teachers strike in Oaxaca, even though it has involved hundreds of

thousands of

indigenous people, the EZLN and its “Other Campaign” have played no

role at

all.

1 Benito Juárez, 1806-1872,

became president of Mexico when civil war broke out in 1858 over a

series of

liberal reform laws establishing the separation of church and state and

curtailing ecclesiastical power. After three years of fighting, the

liberals

led by Juárez triumphed. However, when the liberal government

had to suspend

payment of interest on foreign loans, its main creditors, England,

France and

Spain, sent forces to seize the Veracruz customs house. Louis

Napoléon, the

emperor of France, then decided to occupy the whole of the country, and

with

the connivance of Mexican monarchists he selected Maximilian I of the

Austrian

Habsburg ruling house to be emperor of Mexico. Juárez retreated

to the north

where he established an “itinerant republic.” After the defeat of the

South in

the American Civil War, Napoléon withdrew his support from

Maximilian. When

French troops pulled out, the republican forces led by Juárez

retook the

capital in early 1867.

2 Ejidos were lands reserved for common use of the indigenous population during colonial times; under the land reforms following the Mexican Revolution of 1910-17, in Indian areas land was collectively owned by the community as ejidos and periodically parceled out among the members, although generally cultivated in individual family plots.

3 Non-Governmental

Organizations. While supposedly not (directly) funded by local

governments,

many NGOs are funded by imperialist foundations and governments,

particularly

the U.S.

See also:

To contact the Internationalist Group and the League for the Fourth International, send e-mail to: internationalistgroup@msn.com