March 2006

Fight Arroyo with Workers’ Power!

Riot police chase demonstrators after breaking up attempt to march on “people power” monument

February 24 after President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo declared sate of national emergency.

Photo: Bullit Marquez/AP

Not Another EDSA "People's Power"

Fraud, Fight for Workers Revolution!

Build the

Nucleus of a Philippine Trotskyist Party!

Once

again the Philippine political landscape reverberated from the noise of

police

banging up their shields, reminiscent of the martial law years of the

1970s.

Once more, tanks and armored personnel carriers rolled through the

streets of

Manila and lined up outside army headquarters as crowds gathered,

recalling the

coup d’état that set off the EDSA1 “people power”

mobilization and brought down strongman Ferdinand Marcos three

decades ago. Except this time only a few thousand civilians came out to

join

with military “rebels” instead of hundreds of thousands. So Philippine

president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo managed to wriggle out of it, barely,

for

now. Meanwhile, government repression continues to escalate.

“GMA”

proclaimed a state of emergency on February 24, then lifted it a week

later. In

the meantime, she claimed, the country grew “stronger,” and the threat

of a

coup had diminished. More to the point, her masters in Washington let

the

Philippine president know that her move was not opportune: it undercut

the Bush

regime’s claim to be promoting “democracy”; it could set off a hornet’s

nest of

discontent reaching from the poor into the middle class; it was bad for

business, and, most importantly, it threatened to exacerbate tensions

in the

faction-ridden Philippine military. Her hold on the repressive forces

was shaky

at best, and the 5,000 U.S. troops presently in the Philippines would

not be

able to put down a popular revolt. One Iraq at a time is more than

enough for

the Pentagon these days.

Although

the government’s aim in proclaiming the state of emergency was “sowing

fear”

among its opponents, as “Justice Secretary” Raul Gonzalez frankly

avowed, it

didn’t have the desired intimidating effect. There were protests daily,

from

Manila to Mindanao. Although relatively small at first, testing the

depth of

the crackdown, they could mushroom. Maoist guerrillas in the

countryside

stepped up their actions. Yet the bourgeois opposition, after their

coup

plotting fizzled, limited itself to legalistic gestures. Five months

ago it was

calling on the servile Congress to impeach Arroyo; now it “challenged”

her

emergency decree by appealing to the impotent Supreme Court. And as

always the

reformist labor misleaders hitched their wagons to various civilian and

military factions of the ruling class.

Internationally,

there was a slew of protests against Arroyo’s crackdown. Most called

for

ousting Arroyo with “people power” – i.e., for mass mobilization behind

the

civilian/military bourgeois opposition such as brought down

Marcos (EDSA

1) and Joseph Estrada (EDSA 2), installing another capitalist

politician as

president (Corazon Aquino in 1986, Arroyo in 2001). The

Internationalist Group

participated with a very different program in a February 27 picket of

the

Philippine Consulate in New York called by the Gabriela Network. IG

signs

called to “Drive the U.S. Out of Iraq and Philippines,” “Not Another

‘People

Power’ Fraud, But Workers Revolution!” “No Alliances with Trapos2,

AFP3 and Church – Workers to Power!” and “Smash GMA State of

Emergency with

Workers

Power!”

“GMA

lifts state of emergency...But crackdown continues,” declared the front

page of

the Philippine Daily Inquirer (4 March). The police are

continuing to

carry out arrests without warrants, threatening to ban any

demonstrations

without official permits and are monitoring the media for “sedition.”

Six center-left

Congressmen are still holed up in the House of Representatives, with

cops at

the door to arrest them if they step outside. Others on a pick-up list

of 59

individuals charged with rebellion are still being sought. Rep. Crispin

Beltran

is still being held by the Philippine National Police (PNP), who keep

switching

charges against the leftist former labor leader in order keep “Ka

(comrade)

Bel” in custody. And union leaders are still being gunned down by what

police

and military assassins.

In

short, the Philippines is undergoing “creeping martial law.” As the

government’s isolation deepens, it resorts to increasingly dictatorial

measures

to cling to office. The question is how to fight it. “GMA” is still in

Malakanyang Palace largely because the fractured civilian/military

bourgeois/reformist opposition lacks coherence. But the task is not to

find a

new figurehead to preside over a “reformed” capitalist regime. That

would

preserve power in the hands of the same reactionary forces that have

ruled the republic

since the United States granted the Philippines semi-colonial

independence in

1946. Rather, proletarian revolutionaries must seek to mobilize the

working

class, at the head of the urban poor, the peasantry and oppressed

ethnic/national minorities, in a fight to “Sweep away GMA – Workers

to

power!”

Three

Days in February

On

Friday, February 24, Arroyo issued Presidential Proclamation No. 1017,

decreeing a state of emergency throughout the country. Her General

Order No. 5

implemented this by outlawing “actions ... obstructing governance,

including

hindering the growth of the economy and sabotaging the people’s

confidence in

government, and their faith in the future of this country.” Arroyo

authorized

military and police to make arrests without warrants, ban

demonstrations and

gatherings, take over newspapers and broadcast media, and generally

“prevent or

suppress ... any act of insurrection or rebellion, and to enforce

obedience to

all ... decrees, orders and regulations promulgated by me personally or

upon my

direction.”

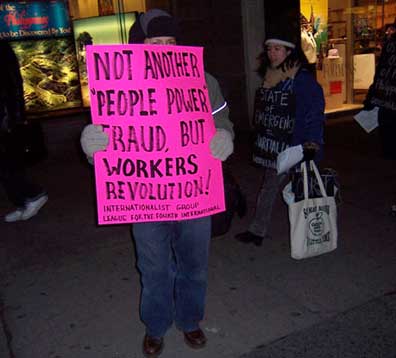

Internationalist

Group/League for the Fourth International at February 27 New York City

protest against Philippines state of emergency. (Internationalist photo)

Internationalist

Group/League for the Fourth International at February 27 New York City

protest against Philippines state of emergency. (Internationalist photo)

Ironically,

this blueprint for personal dictatorship was proclaimed on the 20th

anniversary

of the downfall of Marcos, who had established martial law 14 years

earlier.

The date was no accident. Arroyo claimed that a coup d’état was

being prepared

by an unholy alliance of communists and military officers, to be

carried out

during February 24 demonstrations marking the 1986 “people’s power”

revolt.

Coup plot or not, a big turnout at these demonstrations would certainly

have

shaken the GMA government, which has long lacked “the people’s

confidence,” for

sure since proof surfaced last year that the gang in Malakanyang (the

presidential palace) brazenly stole the 2004 election4.

Arroyo’s

PP 1017 was easily confused with Marcos’ infamous Proclamation 1081

that

established martial law in 1972. Indeed, in briefing the press, AFP

chief of

staff general Generoso Senga twice referred to Arroyo’s decree as

“1081.” With

the authority of General Order 5, police occupied the offices of the Daily

Tribune, a paper that had championed “Oust Gloria” protests,

seizing the

Saturday edition. At least nine newspapers were shut down, radio and

television

broadcasting stations occupied and opposition figures ordered to be

arrested,

as was a University of the Philippines (UP) professor and newspaper

columnist.

The

February 24 demonstrations proceeded anyway, turning into protests

against the

government crackdown. After school classes were canceled and rally

permits

revoked, Arroyo declared the State of National Emergency at 1 p.m., The

first

demonstration to be attacked was that of Laban ng Masa (Masses’ Fight),

with

about 5,000 to 7,000 participants. After the three main leaders of the

social-democratic Akbayan (Citizens’ Action Party) were seized, the

march was

broken up by police batons and water cannon; 62 were arrested,

including a

six-year-old and eleven other minors, charged with inciting to

sedition! An

announcer on radio station DZMM asked, “How can a 6-year-old kid incite

sedition when he is still sucking milk from a bottle?”

By

late afternoon, some 10,000 to 12,000 demonstrators in the larger

“national

democratic” (ND) bloc, associated with the Stalinists, massed in the

Makati

business district, but were blocked by police from linking up with the

“civil society”

groups led by ex-president Corazon Aquino. That third march (of the

bourgeois

opposition) was allowed to proceed to lay a wreath the shrine for the

former

president’s husband, Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino, murdered by Marcos’ agents

in

1983. By 6 p.m., the police proceeded to brutally disperse the ND bloc.

On

Saturday, a list was issued of 59 individuals charged with “rebellion.”

First

to be seized was Crispin Beltran, a member of Congress and spokesman

for the

Anakpawis (Toiling Masses) party list. At a loss for any other pretext,

“Ka

(comrade) Bel” was arrested on a warrant from the Marcos regime (on

charges of

inciting rebellion) in 1985 (!) when Beltran was an official of the

Kilusang

Mayo Uno (KMU – May 1st Movement) union group. Several other leftist

legislators, including Satur Ocampo of the Bayan Muna (People First)

and Lisa

Maza of the Gabriela women’s party lists escaped arrest and were put

under

detention in the House of Representatives. Retired Philippine

Constabulary

chief Gen. Ramon Montano was seized on a golf course.

Also

on the government’s arrest list was former president Joseph (“Erap”)

Estrada,

accused of financing the “coup plot,” who barricaded himself inside a

hospital

room; Senator Gregorio (“Gringo”) Honasan, the former colonel and

commando

leader reputedly involved in every coup and attempted coup in the past

two

decades, who has not been located so far; Jose Maria Sison, the

founding

chairman of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), now in exile

in the

Netherlands where writes as a political advisor to the National

Democratic

Front (NDF); Gregorio (“Ka Roger”) Rosal, leader of the New People’s

Army

(NPA); plus other leftists, some in exile or already in jail.

Arroyo

denounced the political opposition of conspiring with “authoritarians

of the

extreme Left represented by the NDF-CPP-NPA and the extreme Right,

represented

by military adventurists” who are “now in a tactical alliance” and “a

concerted

and systematic conspiracy” to “bring down the duly constituted

government elected

in May 2004” (Philippine Daily Inquirer, 25 February). This

claim

elicited general hilarity. The Philippines has been convulsed by months

of

demonstrations following the leak of tape recordings showing that those

elections were stolen by GMA working together with top generals. And it

was

well-known that discontent was rife in the military over rampant

corruption and

the way top officers had proffered their services to Arroyo. The

government

claimed to have uncovered an “Operation Hackle” in mid-February.

On

Sunday, February 26 came the showdown with the military, which turned

into a

comic opera scene. First, Col. Ariel Querubin marched his 1st Marine

Brigade

into Marine headquarters to protest the sacking of the corp’s

commandant. He

was accompanied by lawyers and civilian supporters of the RAM and Laban

ng

Masa. Tanks, V-150 armored personnel carriers and Simba light armored

tanks

lined up outside. Querubin called on people to mass outside the base to

“protect the Marines.” But this never materialized, as police

surrounded the

whole of Fort Bonifacio (HQ of the Philippine Army and Marines). Who

did show

up were various trapos, former president Aquino and Imee

Marcos,

daughter of the dictator, but they were denied entry as well. By 11

p.m.

Querubin announced, to the consternation of his civilian backers, that

it was

all over and the Marines would follow orders of the chain of command.

Philippine president

Gloria Macapagal Arroyo chats with Brig. Gen. Danilo Lim, head of Scout

Rangers special forces regiment on January 31. Three weeks later Lim

was arrested for rebellion. (Photo:

AFP)

Philippine president

Gloria Macapagal Arroyo chats with Brig. Gen. Danilo Lim, head of Scout

Rangers special forces regiment on January 31. Three weeks later Lim

was arrested for rebellion. (Photo:

AFP)

There

is no doubt that various clans in the faction-ridden officer corps were

talking

about booting out Arroyo, among them veterans of previous coup

attempts. This

included the Revolutionary Patriotic Alliance (RAM, led

by

Honasan, who harks back to the group that overthrew Marcos in 1986);

the Young

Officers Union (YOU, which in 1989 tried to overthrow the

Aquino

government), including Brig. Gen. Danilo Lim, head of the elite Scout

Rangers

regiment, and Marine Col. Querubin; the Soldiers of the Filipino

People (Marcos

loyalists led by Gen. Zumel), who in 1995 together with the RAM and YOU

was

amnestied by the government of President (former AFP chief of staff)

Fidel

Ramos; and the Magdalo group of young officers who in

July 2003

staged a mutiny against Macapagal Arroyo by holding an “armed press

conference”

in the Oakwood luxury hotel5.

It

is also clear that the military plotters were in contact with business

leaders

and bourgeois politicians. Time Asia (24 February)

reported on a

meeting in the home of Jose Cojuangco, brother of ex-president Corazon

Cojuangoco Aquino and a leading capitalist. In a “you are there”

account, the magazine

noted that “plans were being hatched for what one of the ringleaders

called a

‘withdrawal of support’ from President Arroyo” by military chiefs. One

of the

businessmen phoned “a person he identified as an American official in

Washington, assuring him that the post-coup regime would still be

friendly to

the U.S.” Later, they spoke with General Lim, and “over the speaker

phone, Lim

confirmed that it was ‘all systems go’ for the planned movement against

Arroyo.” At the EDSA memorial, “they would be met by a contingent of

Catholic

bishops,” and a Marine general would read a statement disavowing

Arroyo.

But

it was not to be. General Lim was arrested a few hours later.

“Creeping

Martial Law”

This

was the second time in recent months that Gloria Macapagal Arroyo

managed to

escape shipwreck in a political storm. But despite her statement in

proclaiming

the state of emergency – “As commander-in-chief, I control the

situation” –

that is far from the case. What is true is that her regime has become

increasingly

bonapartist6,

with a

steady drumbeat of dictatorial actions. Immediately after issuing

Presidential

Proclamation 1021 lifting PP1017, the government said that the

left-wing

legislators would be seized if they set foot outside the Philippine

Congress

and the individuals for whom arrest orders had been issued were still

being

sought. On March 8, an International Women’s Day march of some 10,000

demonstrators was brutally dispersed by the police, who clobbered

marchers with

their batons and arrested Akbayan Rep. Risa Hontiveros-Baraquel and

Alliance of

Progressive Labor (APL) secretary-general Josua Mata.

The

state of emergency was only a continuation of the escalating repression

of

recent months. As of December 2005, the human rights organization

Karapatan

reported that roughly 3,500 people had been victimized by the

government during

the previous eleven months. This includes bombings, indiscriminate fire

on

demonstrators, and salvagings (summary executions). Following the

assassination

of Nestlé union president Diosdado “Ka Fort” Fortuna in September7,

Ricardo Ramos, the president of the Central Azucarera de Tarlac Labor

Union

(CATLU) at Hacienda Luisita was murdered in October. Hacienda Luisita,

owned by

the Cojuangcos, was the site of a massacre of up to 14 people in

November 20048

during a bitter strike that lasted an entire year. And on March 17,

Tirso Cruz,

a member of board of directors of the United Luisita Workers’ Union

(ULWU) was

shot and killed by gunmen on a motorcycle.

In

addition, there are the army massacres of peasants suspected of being

sympathizers of the Maoist NPA, such as the killing of ten unarmed

civilians at

Palo, Leyte in November. From February to August, at least 56 people

were

killed or missing in Samar while it was under the boot of Gen. Jovito

Palparan

(now in Tarlac). In Mindanao, where there is a continuing war for

secession and

independence of the Moro people, there have also been hundreds of

reported

attacks by the military on the civilian population affecting tens of

thousands

of people. Church workers and journalists

have been targeted in this wave of repression.

According to

the May 2005 report, Marked for Death, by the Committee to

Protect

Journalists, “the Philippines is the most murderous country of all,”

with far

more media workers killed than even in Iraq. While the anti-communist

CPJ

reports 22 Filipino journalists murdered since 1980, Philippine human

rights

groups report 39 killed since Arroyo took office in 2001, with 12

assassinated

last year alone.

Since

the defeat in Congress of the drive to impeach President Macapagal

Arroyo last

September9,

the government has multiplied its repressive measures. Among these are

the

“Calibrated Preemptive Response” (CPR) policy codified in Executive

Order 464,

allowing the police to ban all kinds of rallies and protests that

“continue to

subvert the economy and peace and order of the country,” as GMA

spokesman

Ignacio Bunye put it. Where previously demonstrations were given a few

minutes

to disperse, under CPR the police immediately start indiscriminately

attacking.

The most prominent of these attacks was last October 15 when water

cannon were

sent to disperse several hundred marchers headed by a former vice

president and

three Roman Catholic bishops. EO 464 also prohibits any government,

military or

police official from attending Congressional inquiries without

authorization

from the president herself.

When

Malakanyang refused to let cabinet officials testify in budget

hearings,

Congress retaliated by passing a one-peso budget for those departments

whose

secretaries did not show up. The administration’s response was to

embrace

proposals for “Charter Change” (“Cha-Cha”). When put forward by former

president Fidel Ramos amid calls for Arroyo’s resignation last July,

this plan

for a parliamentary system was claimed to be more democratic than a

presidential system, by making the head of government responsible to

Congress.

Instead, GMA wants to use it to discipline Congress. To drive the point

home,

Arroyo set up a Consultative Commission (“Con Com”) which concocted a

plan to

cancel the 2007 legislative and local elections (“No-El”), to prevent

an

opposition sweep. This would have let the president stay on until 2010

when she

could run for parliament and become prime minister, thus perpetuating

her grip

on power.

The

“No-El” scheme elicited shrieks of protest from the trapos,

fearing for

their sinecures, and was shelved, at least temporarily. Arroyo’s next

ploy was

the state of emergency, which her administration had been working on

since last

September at least. As she was forced to retreat on that as well, the

government is making a push to ram through an “anti-terrorism” bill

that was

bogged down in committee. This would define “terrorism” as “the

premeditated,

threatened [or] actual use of violence, force, or by any other means of

destruction perpetrated against person/s, property/ies...with the

intention of

creating or sowing a state of danger, panic, fear, or chaos to the

general

public, group of persons or particular person....” This elastic

definition

could outlaw everything from a rally to a strike, or even calling for

or

talking about a strike. The government brought in a United Nations

delegation

to bolster its call for an “anti-terror” law.

Popular

Front Dead End

This

brief survey of the government’s latest moves demonstrates what the

League for

the Fourth International has been saying for some time: that Arroyo,

who has

campaigned under the slogan for a “strong republic,” is relentlessly

pushing to

shore up her shaky rule with bonapartist measures. For Marxists,

pointing to

the danger of a police state, military dictatorship or other form of a

bourgeois “strong state” underscores the need for workers revolution.

Trotskyists stress that the tendency to restrict and do away with even

the most

basic bourgeois “democratic” rights is inherent in capitalism in this

period of

imperialist decay, going hand in hand with the full-scale assault on

workers’

gains. We point out that the overthrow of the original bonapartist

regime, the

French Second Empire of Louis Napoleón, led to the Paris

Commune, the first

workers government in history10.

For

reformist socialists, however, pointing to the bonapartist character of

a

regime is used as an excuse for advocating a coalition with

“democratic” sectors

of the bourgeoisie. Typically, such a government is termed “fascist,”

although

it lacks the mass base of enraged petty bourgeois that characterized

the

European fascist movements, resting instead on the military and police

apparatus. And the revisionists’ response is to call for a “popular

front” to

combat it on the political terrain of bourgeois democracy,

rather than

fighting for workers revolution. As in Sukarno’s Indonesia in 1965 or

Allende’s

Chile in the early ’70s, popular-frontism is paid for in workers’

blood, paving

the way for fascist and bonapartist reaction by acting as a roadblock

to

proletarian revolution.

In

the Philippines today, the policy of virtually the entire left in the

“Oust

Gloria” movement is to make common cause with the bourgeois

civilian/military

opposition. In the immediate aftermath of Arroyo’s proclamation of a

state of

emergency, NDF “chief political consultant” Jose Maria Sison issued a

February

25 statement declaring, “To oust the Arroyo regime, it suffices for the

legal patriotic,

progressive and other anti-Arroyo forces and their allies among the

active and

retired military and police forces to do their best in mustering their

own

respective following and in drawing the broad masses of the people to

gigantic

mass actions.” Sison added that “among the opposition parties, the

legal forces

of the national democratic movement and the ranks of retired and active

anti-Arroyo military and police officers in the broad united front

there is a

growing common desire to form a transition council” to negotiate peace

with the

NDF.

The

Communist Party of the Philippines put out a special issue of its

publication, Ang

Bayan (27 February), headlined “Resist Gloria Arroyo's new fascist

dictatorship,” and calling for NPA units to “coordinate with the

anti-Arroyo

and other friendly units within the AFP and PNP.” In another issue of Ang

Bayan (12 March), Sison suggests formation of a “Roundtable Council

of

Advisors” to include “former presidents” and other leading figures, and

a

“Unified Command” to include “major groups of retired and active

military and

police officers.” This is in line with the CPP’s Stalinist policy of

“two-stage

revolution,” the first stage being (bourgeois) “democratic” and later

(never)

for socialism. Sison claims the “united front” between Mao Zedong’s

Chinese

Communist Party (CCP) and Chiang Kai-shek’s Guomindang against the

Japanese as

a precedent for allying with “anti-Arroyo military and police

officers.” But

Mao’s call for a “united front” was a dead letter, as Chiang always

concentrated his fire against the Communists.

While

the CPP/NDF/NPA and their “national democratic” camp looked to “major

groups”

of military officers and “former presidents” (Ramos?), various

social-democratic left and not-so-left groups sought a

civilian-dominated

“transition council” to replace Arroyo. According to Bulatlat

(19

March), this included the “Solidarity Movement” headed by former

“defense”

secretary Renato de Villa along with Bayan Muna (People First), Bayan

(New

Patriotic Alliance) and other popular-frontist groups; as well as Laban

ng Masa

(People’s Fight) headed by former University of the Philippines

president

Francisco Nemenzo. The Arroyo government has dreamt up an elaborate

“right-left” coup plot in order to justify arresting a broad array of

opponents. But the “evidence” it presents points only to initial

contacts of

civilian oppositionists, dissident military officers and leftist

leaders. What

it comes down to is they did what Arroyo herself did during EDSA 2,

which put

her in the presidential chair.

Following

the (predictable) defeat of impeachment in the House of Representatives

in

September, the response of the nat-dems was to call for a “people’s

court” to

try Arroyo. This sarsuela (a folk dance of love and hate) – initiated

by Bayan

Muna, Bayan and the KMU – was empty political theater. The purpose of

the “Citizens’

Congress for Truth and Accountability” was “submitting the evidences to

the

people that have not been heard during the impeachment trial,” as

former vice

president Guingona put it (Philippine Daily Inquirer, 26

October) – in

other words, a pretend impeachment. After a couple of hearings, the

play-acting

impeachment predictably fell apart as well.

For

their part, the Partido ng Manggagawa (PM – Workers Party) and allied

groups

(BMP, Sanlakas, Akbayan, Laban ng Masa) organized a “working people’s

summit”

in mid-October, which called for strike action against the regime. The

summit

set a national day of protest “to call for President Arroyo’s removal

and to

express their opposition to the expanded value-added tax law” (Manila

Times,

10 November 2005). The EVAT plan, raising the sales tax from 10 percent

to 12

percent, was adopted at the urging of the International Monetary Fund.

But

while using a more “workerist” or laborite language than the Stalinists

and

national democrats, this bloc is also angling for a popular front. The

aim of

their welgang bayan (people’s strike) is to install a

“transitional

revolutionary government” with sections of the bourgeoisie.

PM

legislator Rene Magtubo says that a “TRG” should foster “the basic

interest of

the working people: just trade, a just debt [!], a democratization of

the

resources,” etc. But in an article in the PM’s paper Obrero

(July 2005),

Sonny Melencio admitted that such a transitional government would

include

“representatives of the bourgeois opposition.” During February 24

protests

against the state of emergency, Melencio, speaking for Laban ng Masa,

declared

that, “We call for a ‘Transitional Revolutionary Government’ which may

just put

people in power who don’t want to go any further, but that is the next

step.”

Moreover, Laban ng Masa leader Nemenzo was reportedly in touch with the

high-ranking AFP officers who planned to “withdraw support” from

Arroyo, and

even organized a “backup” crowd at the UP campus to join with the

Marines (Newsbreak,

14 March).

The

PM/BMP/Sanlakas/Akbayan/Laban milieu was influenced by the late Filemon

“Popoy”

Lagman, shot to death in 2001, who broke from CPP in 1994 after

rejecting the

peasant-based “people’s war” thesis of the Sisonites, which accorded

the urban

working class at most an auxiliary role. But Lagman did not break with

the

Stalinist dogma of a “two-stage revolution.” The Lagmanites’ calls for

workers

action are invariably linked to calls for parliamentary “struggle” and

for

popular-front alliances with the bourgeois opposition. They tack on

demands

against the EVAT to demonstrations for a transitional “revolutionary”

government including businessmen, big landowners, trapos and

generals.

In reality, they are calling for another capitalist government to

provide the illusion

of pro-worker policies while stepping up anti-worker repression and

“reforms,”

as both the Aquino and Arroyo governments have done.

For

Permanent Revolution! Build a Trotskyist Nucleus in the Philippines!

Trotskyists,

in contrast, insist that to fight the escalating repression unleashed

by the

Arroyo government it is necessary to mobilize the working class,

impoverished

peasantry and urban poor on a class basis, to fight for socialist

revolution.

February

24 being the 20th anniversary of the 1986 EDSA “people power” revolt

against

the Marcos dictatorship, there were a host of articles in the press

recalling

that signal event of the last half century of Philippine history. Much

of the

discussion turned on how the left, and the Communist Party in

particular, after

dominating the anti-Marcos struggle for years, was pushed aside at the

crucial

moment by the bourgeois opposition that coalesced around Cory Aquino.

Answering

charges that the CPP was “caught flatfooted” because of its Maoist

strategy

which dismissed the perspective of an urban insurrection, Sison

responded

defensively, saying that a “convergence of various forces” were

responsible for

bringing down Marcos (Philippine Daily Inquirer, 24 February).

But the

fact is that, after boycotting the “snap election,” the CPP

flip-flopped and

supported the military officers movement led by Gen. Fidel Ramos and

Defense

Minister Ponce Enrile.

Despite

its pick-up-the-gun rhetoric and decades of guerrilla warfare, the

CPP’s

strategy from the outset has been guided by the Stalinist program of

popular-frontism – that is, of class collaboration with sectors of the

capitalist class. They have sought not just to win individuals from the

Philippine military (such as then Lt. Col. Victor Corpus, who after a

stint with

the NPA returned to the AFP to become a leading military intelligence

official)

but to ally with “major groups” in the bourgeois officer corps. The

CPP’s

guerrillaist politics amount to “armed reformism,” based on the

petty-bourgeois

peasantry rather than the proletariat and intended to pressure the

ruling

class. From “Ninoy” and Corazon Aquino to Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, the

Sisonites have repeatedly sought political alliances with the bourgeois

“opposition,” which is why they are constantly playing second fiddle to

some

new ruling-class politician. In the aftermath of the recent “state of

emergency,” Sison writes, in a March 15 statement:

“In

the absence of a civilian political opposition strong enough to replace

the

Arroyo regime with a new civilian government, the conditions become

more than

ever fertile for the growth of the people’s armed revolutionary

movement and

likewise for a military coup by military and police officers who

calculate that

they need to remove the stinking Arroyo regime to save the ruling

system from

the armed revolution.”

Yet Sison’s “armed

revolutionary movement” is not aiming

at a revolutionary overthrow of Philippine capitalism; rather it seeks

to

negotiate a role for the CPP within that system.

And

this the CPP’s outlook not only in the Philippines. Thus an article in Ang

Bayan (21 December 2005) on “A united front against the Nepalese

monarchy”

praises the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) for dropping its

“sectarian”

policy toward the bourgeois opposition:

“Previously,

the CPN(M) was too ‘Left’ in relating to the parliamentary parties. The

CPN(M)

one-sidedly regarded them as opportunists and refused to maintain

relations

with them. On the eve of the continuing march of the CPN(M) to victory,

the

party realized that that was an incorrect policy. It has rectified this

sectarianism.”

So according to Sison &

Co., the Nepalese Maoists

were ultra-left sectarians for failing to make a political alliance

with the

bourgeois parliamentary parties, an “error” that has been “rectified.”

In fact,

in both Nepal and the Philippines, the Maoists’ armed struggle has for

years

been aimed at allying with capitalist sectors. The CPN(M) was earlier

in a bloc

with the bourgeois opposition until the latter pushed it out, while the

CPP

supported the ascension of Aquino and Arroyo. Now they are preparing to

repeat

this betrayal.

The

question of how to combat bonapartist regimes in semi-colonial

countries like

the Philippines and Nepal is not a new issue. The so-called “Third

World”

abounds in tin-pot dictators. This has been so ever since the

colonialist

powers granted political independence to their former colonies while

keeping

them economically subjugated and politically dominated by imperialism.

In

fighting against these dictatorships, the Stalinists typically align

themselves

politically with those who portray themselves as democrats. But because

the

tendency toward bonapartist rule in the semi-colonies is inherent in

the

imperialist system, from China in the 1920s to Chile in the 1970s, the

bourgeois

“democrats” repeatedly turn out to be butchers, turning on their left

“allies”

or else opening the way to a bloodbath against the workers and

peasants. Thus

the Stalinist program of “stages,” borrowed from the Menshevik social

democrats, turns into a recipe for bloody defeat.

Leon

Trotsky, co-leader together with V.I. Lenin of the 1917 Bolshevik

Revolution in

tsarist Russia, emphasized the inability of the weak bourgeoisies of

the

economically backward capitalist countries to carry out even the basic

tasks of

the democratic revolution, notably democracy, agrarian revolution and

national

liberation. This was why Trotsky insisted, in his theses on permanent

revolution, on the need for the proletariat, supported by

the

peasantry and led by a communist party, to take power in order to

achieve

democratic demands and proceed to undertake socialist tasks,

expropriating the

bourgeoisie and extending the revolution internationally. This was the

program

of the Russian October Revolution, which is diametrically opposed to

Stalin’s

twin policies of building “socialism in one country” and “revolution in

stages”

elsewhere, which translated into the formation of “popular fronts” with

out-of-power bourgeois forces. As this produced one disaster after

another in

the 1930s, from Germany to Spain and France, Stalin earned the bitter

sobriquet

of being the “great organizer of defeats.”

In

his last essay, which lay incomplete on his desk when he was murdered

by a

Stalinist agent, Trotsky noted:

“[T]he

governments of those backward countries which consider inescapable or

more

profitable for themselves to march shoulder to shoulder with foreign

capital,

destroy the labor organizations and institute a more or less

totalitarian

regime. Thus, the feebleness of the national bourgeoisie..., the

pressure of

foreign capitalism and the relatively rapid growth of the proletariat,

cut the

ground from under any kind of stable democratic regime. The governments

of

backward, i.e., colonial and semi-colonial countries, by and large

assume a Bonapartist

or semi-Bonapartist character; and differ from one another in this,

that some

try to orient in a democratic direction, seeking support among workers

and

peasants, while others install a form close to military-police

dictatorship.”

–Leon

Trotsky, “Trade Unions in the Epoch of Imperialist Decay” (August 1940)

The government of Gloria

Macapagal Arroyo undoubtedly

belongs to variant of semi-bonapartist regimes heading toward naked

military-police rule. What, then, should be the policy of the

proletariat toward

such regimes? It must be the program of permanent revolution,

of the

struggle for workers revolution which alone can spark a thorough-going

agrarian

revolution against the large capitalist landowners who oppress

the

peasantry; which alone can break the yoke of imperialism and achieve

national

liberation; which alone can break the cycle of imperialist-imposed

petty

tyrants who enslave the impoverished masses.

The

Stalinists and social democrats refer to Arroyo as an imperialist

puppet, and

so she is. But what does that mean in practice? That another,

independent,

nationalist bourgeois leader could be installed in her place? Who among

the

endlessly squabbling capitalist politicians and eternally coup-plotting

military officers could stand up to the imperialist puppet masters and

its

thousands of troops in the Philippines? None of them, clearly. Another

bourgeois leader in Malakanyang Palace would inevitably be one more

puppet of

Washington and Wall Street until the imperialist stranglehold is

broken, which

requires proletarian revolution from the semi-colonies to the bastions

of world

capitalism. Trotsky wrote in his “Manifesto of the Fourth International

on the

Imperialist War and The Proletarian World Revolution” (May 1940):

“[T]the

Fourth International knows in advance and openly warns the backward

nations

that their belated national states can no longer count upon an

independent

democratic development. Surrounded by decaying capitalism and enmeshed

in the

imperialist contradictions, the independence of a backward state

inevitably

will be semi fictitious, and its political regime, under the influence

of

internal class contradictions and external pressure, will unavoidably

fall into

dictatorship against the people.... The struggle for the national

independence

of the colonies is, from the standpoint of the revolutionary

proletariat, only

a transitional stage on the road toward drawing the backward countries

into the

international socialist revolution.”

In

the Philippines today, the relentless march toward a bonapartist

“strong state”

regime can only be stopped by a revolutionary mobilization of the

working

class, backed up by the impoverished peasantry and millions of urban

poor. Such

a display of power would attract the support of sections of the

wavering middle

classes who fear chaos and a new Marcos-like regime or military junta.

Playing

political games with the bourgeois opposition and conspiring officers,

as the

reformist left has done in the “oust Gloria” and impeachment campaign,

can only

undercut that struggle. It may even open the door for U.S. imperialism

to

engineer a “change of control” in its Philippine subsidiary, as

Washington did

by replacing Marcos with Aquino.

The

power of the proletariat should be mobilized in the streets and in

strike action

against every attack on democratic rights and every blow against the

livelihoods of the masses. A campaign based on the working class should

be

waged to drive the U.S. troops and agents out of the Philippines. An

international campaign should be waged to free Crispin Beltran and

other

prisoners of the Arroyo regime. Above all, the nucleus of a Trotskyist

party

must be built, exposing the bourgeois politics of the several competing

mini-popular fronts and politically challenging the hegemony of the

Stalinist

and social-democratic reformist politics on the left.

The

League for the Fourth International declares that if the Filipino

working

people are to sweep away the bottomless corruption and brutal

repression of

bourgeois rule and put an end to the mass misery produced by capitalist

exploitation, they require a revolutionary-internationalist,

Leninist-Trotskyist workers party to lead that fight, not only in the

Philippines but throughout Southeast Asia and in the centers of world

imperialism. n

1 Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA) is the ring highway encircling central Manila, on which Fort Bonifacio, the HQ of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) is located and where crowds gathered in response to appeals by Catholic Cardinal Sin and in support of military mutineers who brought down Marcos in 1986.

To contact the Internationalist Group and the League for the Fourth International, send e-mail to: internationalistgroup@msn.com