September 2024

Then and Now: Democrats’ War Abroad, Police Brutality at Home

The 1968 DNC Protests

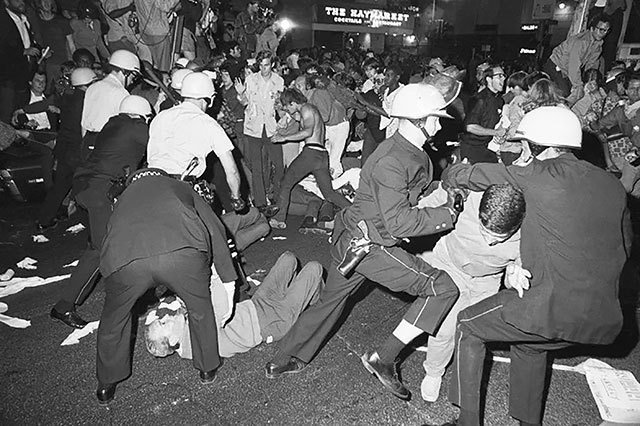

Police attack protesters outside Conrad Hilton hotel during 1968 Democratic

National Convention in Chicago. (Photo: Bettman Archive)

By Sade

As the Democratic National Convention assembled this August, its organizers put final touches on the red-white-and-blue spectacle promoting “joy” for a new Commander-in-Chief of U.S. imperialism. They hoped the stage show’s hoopla and slick graphics would blot horrific images of the U.S./Israel war on Gaza out of viewers’ minds, together with those of last spring’s violent police repression against pro-Palestinian campus protests. Yet the fact that the quadrennial imperialist shindig was being held in the city of Chicago inevitably harkened back to the infamous DNC of 1968. It too was held in Chicago, amidst nationwide protests against the mass murder being carried out by another Democratic administration: U.S. imperialism’s dirty colonial war on the workers and peasants of Vietnam.

In August of 1968, it seemed as if U.S. society was coming apart at the seams. With the military draft in full swing, the number of U.S. troops in Vietnam had reached over 535,000. In April of that year, Martin Luther King was assassinated. In June, Robert Kennedy. At Columbia University, police had violently removed student strikers protesting against the war and racism. Americans watched on TV as the U.S. dropped napalm bombs and burned villages in Vietnam in the name of “freedom” and “democracy,” while massive antiwar protests and “riots” against racist police terror occurred in one city after another. Internationally, the general strike of 10 million French workers in May ’68 dramatically showed the potential for socialist revolution.

Having assumed the presidency after the assassination of JFK in 1963, Democrat Lyndon B. Johnson claimed U.S. warships had been attacked off the coast of Vietnam, as a pretext to escalate the war. Despite the massive flow of U.S. weaponry and troops, the heroic fighters of the National Liberation Front (“Viet Cong”) were winning, as the NLF’s January 1968 Tet Offensive demonstrated to the world. Johnson, in the gutters of public opinion, decided not to run for reelection. Revolutionary Trotskyists called for the imperialists’ defeat and victory to the Vietnamese revolution. But (similar to most groups organizing protests at this year’s DNC), reformists saw the 1968 convention as “an opportunity to put on a lobbying effort aimed at the delegates.”1

That effort reflected the growth of “bourgeois defeatism” among some capitalist politicians who had come to consider the war on Vietnam unwinnable. A number now postured as “peace” candidates. Leading up to the 1968 DNC, the Democratic Party was divided: Hubert Humphrey, who as LBJ’s vice president was directly co-responsible for the war (sound familiar?), was favored for the presidential nomination by those who wanted to “stay the course” in Vietnam. Opposed to Humphrey were supporters of “doves” (bourgeois defeatists) like Senator Eugene McCarthy, who sought an exit route from the war in order to better safeguard long-term imperialist interests.2 A whole layer of ’60s activists responded to the call to “Get Clean for Gene” and do Democratic Party donkey work for his campaign.

Imperialist War Abroad, Repression “At Home”

Imperialist war on

Vietnam. In January 1968, the National Liberation Front

(“Viet

Imperialist war on

Vietnam. In January 1968, the National Liberation Front

(“VietCong”) launched the Têt offensive. As U.S. forces counterattacked, a major was

quoted saying it was “necessary to destroy the town to save it.” Israeli spokesmen

cite U.S. tactics in Vietnam to justify leveling Gaza. (Photo from Ken Burns’ documentary The Vietnam War)

Planning to protest outside the 1968 DNC were thousands from a range of groups, from liberal and reformist outfits to Abbie Hoffman’s “Yippies” (who nominated an actual pig for president) to currents like Students for a Democratic Society that had moved to the left under the impact of the war. Chicago’s mayor (from 1955 to 1976) was Richard J. Daley, a notoriously corrupt and racist mainstay of the national Democratic Party machine determined to “keep order” in the city. This meant deploying 12,000 police officers backed up by 6,000 National Guardsmen and 7,000 army troops. Daley had previously deployed the forces of state violence on a massive scale in April. When black neighborhoods exploded in outrage after King’s assassination, the mayor called in the Guard and federal troops, while specifically instructing police to “shoot to kill” arsonists and “shoot to maim or cripple” looters.

From the first night of the Democratic convention, police violence was rampant, with the cops bloodying protesters and reporters in Lincoln Park and making a particular point of smashing news photographers’ cameras. TV news showed convention security officers roughing up Dan Rather, who was then a reporter for CBS news, while on the streets and in Lincoln Park the cops went into a frenzy of brutality. (Documenting the cops’ “unrestrained and indiscriminate violence,” an official report later spoke of a “police riot” – though in fact the Chicago PD’s violence was ordered by Mayor Daley.)

In a detailed account, a journalist eyewitness reported:

“City hospitals were telling demonstrators not to bring their wounded to the regular hospital emergency rooms because cops were waiting at the door to jam the wounded into paddy wagons. The cops stormed into improvised hospitals … and jerked transfusion needles out of arms and, broken bones or no broken bones, crammed the wounded into vans.”

– John Schultz, No One Was Killed: The Democratic National Convention, August 1968 (1969)

Wednesday, August 28, the third night of the convention, was a bloodbath: Daley delivered on his promise to use force to prevent any protesters from gathering near the convention center. Thousands gathered on Michigan Avenue, near the Conrad Hilton hotel where many delegates were staying. Soon after, cops in riot gear, together with National Guardsmen, began their assault on the protesters. For 17 minutes straight, as filmed by news media, they mercilessly brutalized demonstrators, striking them to the ground with clubs, beating them with batons, then dragging them by their limbs to police vans. They used tear gas and Mace and spared neither reporters nor medics. As reported by The New York Times (29 August 1968):

“Even elderly bystanders were caught in the police onslaught. At one point, the police turned on several dozen persons standing quietly behind police barriers in front of the Conrad Hilton Hotel watching the demonstrators across the street.

“For no reason that could be immediately determined, the blue-helmeted policemen charged the barriers, crushing the spectators against the windows of the Haymarket Inn, a restaurant in the hotel. Finally the window gave way, sending screaming middle-aged women and children backward through the broken shards of glass.

“The police then ran into the restaurant and beat some of the victims who had fallen through the windows and arrested them.”

“Law and order” was their watchword. Scenes of the attacks interrupted TV coverage of convention proceedings and were broadcast across the world. The televised police violence against antiwar protesters on Chicago’s streets was another example of how imperialist war abroad means escalated repression “at home.” Less publicized was the fact that four months previously, at least nine people were killed, hundreds were injured and over 2,000 arrested when police savagely attacked residents of Chicago’s black West Side community after the assassination of MLK.

Repression on the home

front. During the August 1968 Democratic National

Convention, the National Guard was mobilized to keep antiwar

and civil rights protesters away from the meeting. Today,

Republican Donald Trump and Democrat Kamala Harris try to

outdo each other with “law and order” rhetoric.

Repression on the home

front. During the August 1968 Democratic National

Convention, the National Guard was mobilized to keep antiwar

and civil rights protesters away from the meeting. Today,

Republican Donald Trump and Democrat Kamala Harris try to

outdo each other with “law and order” rhetoric. (Photo: Life Magazine)

As cops were brutalizing protesters on the streets, liberal Connecticut senator Abraham Ribicoff took to the convention stage to nominate George McGovern, one of the Democratic “doves,” for president. (McGovern would subsequently become the Democratic candidate in 1972.) In a famous face-off, Ribicoff denounced the “Gestapo tactics” of the Chicago police and a gesticulating Daley yelled curses at him from the convention floor. Ultimately Johnson’s man Humphrey would receive the nomination, only to lose in the November elections to Republican Richard Nixon, who claimed to speak for a “silent majority” turned off by protests and challenges to the status quo.

Aftermath

The upheavals of 1968 had a big impact on many young people

as the Vietnam War and opposition to racist repression

continued to polarize U.S. society. The decade had already

seen the growth of the civil rights movement, rebellions

against police terror from Harlem to Watts, the Cuban

Revolution’s defiance of liberal icon Kennedy’s attempts to

crush it, and a seemingly endless U.S. onslaught against

Vietnam. Whole layers of youth who had once admired figures

like JFK now despised and rejected the Democratic Party.

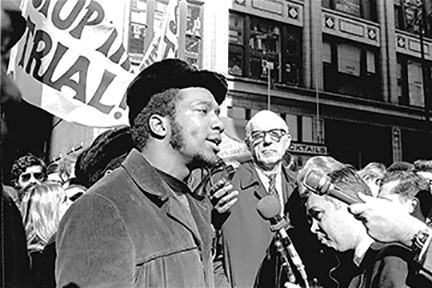

In March 1969, eight activists who had been leading figures in the DNC protests were indicted by a grand jury on charges of “conspiracy” and crossing state lines with intent to incite riots. Like the police brutality during the convention itself, this lurid frame-up trial had an impact on the consciousness of millions. Few could forget the image of defendant Bobby Seale, a co-founder of the Black Panther Party (BPP), gagged, bound and chained in the courtroom on the orders of the judge, who sentenced him to four years in jail for “contempt of court.”

In December 1969, an agent that the Chicago Police Department had placed in the BPP laid the basis for the raid on the party’s local headquarters in which Fred Hampton, one of the Panthers’ foremost young leaders, was murdered together with party activist Mark Clark. The assassination was part of COINTELPRO, the FBI “counterintelligence program” in which dozens of Panthers were murdered or imprisoned on frame-up charges. One who is still in prison to this day is radical black journalist Mumia Abu-Jamal. Fighting for Mumia’s freedom is an important part of the struggle against racist repression today. (See “Toward Black Liberation” in this issue of Revolution.)

Fred Hampton, leader of the Black Panther Party in Chicago,

at a rally outside the federal courthouse in October 1969

protesting against the trial of the Chicago Seven, who were

accused of conspiracy to riot during

Fred Hampton, leader of the Black Panther Party in Chicago,

at a rally outside the federal courthouse in October 1969

protesting against the trial of the Chicago Seven, who were

accused of conspiracy to riot duringthe 1968 Democratic National Convention. A little over a month later, on 4 December 1969 he was murdered in an FBI-instigated raid by the Chicago Police, in which Panther Mark Clark was also slain. (Photo: Associated Press)

In 1972, George McGovern won the Democratic presidential nomination (but lost to Nixon). The McGovern campaign accelerated the process seen in 1968’s McCarthy campaign, channeling many young activists into the Democratic Party of the A-bomb in Hiroshima and napalm in Vietnam. Soon, the end of the draft would take the air out of the antiwar movement, while more than a few volunteers in McGovern’s campaign made it a steppingstone toward a career in bourgeois politics. (Among them were Bill and Hillary Clinton, who worked together on the McGovern campaign; he would become Commander-in-Chief and she Secretary of State of U.S. imperialism.) Though shaken by the upheavals of the Sixties, U.S. politics continued under the stranglehold of the capitalist parties. The historic task of breaking that stranglehold and forging a revolutionary workers party remains on the agenda.

The U.S. war that brought the billy clubs of Chicago cops down on the heads of young protesters in 1968 caused the death of over 3 million people in Vietnam. “Peace” did not come through the machinations of Democratic imperialist politics. The victorious revolutionary struggle of the Vietnamese masses defeated the U.S. imperialists and in 1975 swept away the puppet “South Vietnam” regime they had installed.

And the Democrats? Fifty-six years after their 1968 convention nominated yet another war criminal, they – and their rivals/partners in imperialist rule, the Republicans – continue their genocidal crimes.

Both these aspects of ’68’s aftermath remind us that only revolution can bring justice. ■

- 1. PBS Retro Report “1968 Democratic National Convention” (2020) interview with Tom Hayden, who eventually became a Democratic politician but in 1968 was a New Left organizer of DNC protests. (Another echo of the ’68 convention protests is the “Cease Fire Now” demand you can see in some photos of placards carried then.)

- 2. For more on these topics, see “U.S. Imperialism’s War Crimes and Mass Murder in Vietnam” and “Vietnam: A Historic Defeat for U.S. Imperialism,” Revolution Nos. 10 (October 2013) and 15 (September 2018).