October 2025

Elizabeth Catlett, From D.C. to Mexico City Exile

The Inspiring Odyssey

of a Black Radical Artist

By AJ and Ray

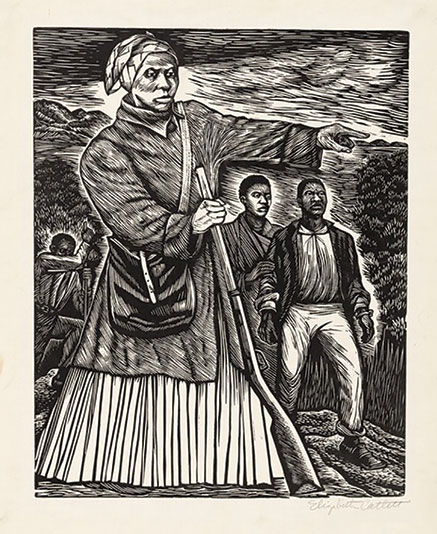

Untitled (Harriet

Tubman), 1953, by Elizabeth Catlett, Taller de Gráfica

Popular.

Untitled (Harriet

Tubman), 1953, by Elizabeth Catlett, Taller de Gráfica

Popular.Early this year, activists from the Revolutionary Internationalist Youth (RIY) and the Internationalist Clubs at the City University of New York visited the Brooklyn Museum to view the exhibition “Elizabeth Catlett: A Black Revolutionary Artist and All That It Implies.” The topics addressed in the art of Elizabeth Catlett (1915-2012) are of great interest to us as young revolutionaries. But despite this, and despite her importance in the history of art and leftist politics, the truth is that until recently most of us had never heard of her.

That changed in summer 2024 when RIY and Internationalist Club members made a museum trip – accurately described as “exhilarating” in the last issue of Revolution – to the “Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism” exhibit at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. In an article about this (with great graphics!) and a short accompanying piece on Elizabeth Catlett, comrades expressed their excitement at seeing one of her paintings there and hearing about her for the first time.1 She seemed like a precursor of things we’re fighting for, like black liberation, women’s emancipation, international solidarity and the ability of rebellious artists and activists like her to express themselves freely in the face of repression and bigotry. We wanted to learn more about her.

So it was with considerable anticipation that we went to see the special, extensive exhibition of Elizabeth Catlett’s work at the Brooklyn Museum, which featured over 200 of her sculptures, engravings, etchings and paintings. It was a great experience. Yes, the exhibit curators downplayed the “red” (communist) background and context of much of her story, but this was not a surprise, having seen how most of the bold redness of Langston Hughes, Aaron Douglas and other Harlem Renaissance greats had been bleached out of last year’s exhibit at the Met. The great thing about the Catlett exhibition was seeing so much of her inspiring and beautiful work, in so many different media and styles, all in one place.

Some of Why It Spoke to Us

A huge fist in gorgeously grained deep-brown wood greeted us in one of the museum’s main halls, not far from another large wooden sculpture of a young black woman raising her fist high – both made by Elizabeth Catlett in Mexico City, in 1968. That was a year of radical upheavals in one country after another, from the Vietnamese National Liberation Front’s Tet Offensive against U.S. imperialism to France going to the brink of workers revolution to huge student antiwar protests from Tokyo to Berkeley and NYC. We learned that Catlett’s work was a point of connection between black freedom struggles in the U.S. and the 1968 mass student strike at UNAM, the National Autonomous University of Mexico, where she taught sculpture and actively supported the student movement (which her sons were also part of).

During visit to the exhibit “Elizabeth Catlett: A Black Revolutionary Artist and All

That It Implies” at the Brooklyn Museum. In background: the artist in her studio. (Revolution photo)

As our Mexican comrades of the Grupo Internacionalista, and thousands of others, chant at Mexico City marches to this day, “¡Dos de octubre no se olvida!”: October 2nd will never be forgotten. On that day in 1968 the Mexican Army bloodily repressed the students’ mass protest movement, murdering hundreds on the eve of the 1968 Summer Olympics held in the Mexican capital. It was on the medal stand at those Olympics that black U.S. athletes John Carlos and Tommie Smith famously raised the clenched-fist salute, which originated in workers struggles, was widely popularized by the Communist movement during the Depression and in the 1960s was widely adopted as a symbol of black militancy in the struggle against racist oppression.

Not far from the huge fist sculpture at the Brooklyn Museum exhibit were several dramatic lithographs and linocuts (prints made from a block of linoleum) that Catlett made in Mexico in 1969-72, focusing on repression and resistance in the United States. Among these were a particularly striking one on police terror and “ghetto riots” in cities across the U.S., titled Watts/Detroit/Washington/Harlem/Newark, and Torture of Mothers, in which the head of a black woman holds the image of a murdered black boy. Looking at these images today, we cannot help connecting them to the fact that despite even the massive protests of 2020, racist police terror continues unabated in capitalist America.

While Catlett’s own politics were largely shaped by the Communist Party milieu that developed in the 1930s and ’40s, works included in the exhibit show her vivid sympathy for Malcolm X, the Black Panthers and others who were key to the New Left radicalism of the ’60s. Portrayed as well in her exhibited works were major figures in black history going back to the poet Phyllis Wheatley (1753-84), among them Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, Paul Robeson and many others. One of our favorites was the anonymous union organizer shown in the linocut My Role Has Been Important in the Struggle to Organize the Unorganized from Catlett’s 1946-47 series The Negro Woman (later titled The Black Woman).2

A large statue in polychromed cedar, from 1971, shows a black woman with her wrists manacled behind her back. Titled Political Prisoner, it evokes Angela Davis, while a brightly colored 1972 print titled Angela Libre celebrated Davis being freed from jail early that year. It turns out that Elizabeth Catlett was prominent in Mexico’s “Free Angela” committee and vocally connected her imprisonment in the U.S. to that of hundreds of survivors of the October 1968 massacre in Mexico. The more deeply we got into the museum exhibit, the more we understood about how Catlett incorporated motifs and techniques ranging from African sculpture to pre-Columbian terra cotta coils to the mural paintings of José Clemente Orozco; and how consciously she connected the history and struggles of exploited and oppressed people in the U.S. with those in Mexico. Some of the artwork also addressed solidarity with the Cuban Revolution and the fight against U.S. imperialism in Central America. Despite the U.S. and Mexican governments’ attempts to silence her, the courageous artist/activist never backed down.

An Artist’s Education in Jim Crow America

There Are

Bars Between Me and the Rest of the Land, 1946, from

the series The Negro Woman (later renamed The

Black Woman).

There Are

Bars Between Me and the Rest of the Land, 1946, from

the series The Negro Woman (later renamed The

Black Woman). How was it that Elizabeth Catlett, whose roots were in the U.S. South, was by 1968 a long-standing part of Mexico’s vibrant and politicized artistic political life? It was in Washington, D.C., where Jim Crow reigned, that she was born in 1915 – and where today in 2025, black Washingtonians face a racist occupation by the National Guard. Her odyssey personifies aspects of the “transnational” left (a term particularly used with reference to leftist artists and activists who moved between the U.S. and Mexico)3 that are little known today. Born in Freedmen’s Hospital to two D.C. public school teachers, she went to a high school named after influential black poet Paul Laurence Dunbar. Seeking to pursue her interest in art, in 1932 she applied to the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University), but it denied her entry. Why? Because Catlett, the granddaughter of slaves, was black.

This experience of racist discrimination was part of what led her into a life of political activism. Accepted into Howard, one of the foremost “HBCUs” (historically black colleges and universities), she studied under faculty members who had been part of the Harlem Renaissance and were teaching art history as well as painting, printmaking and other subjects. During this period she started researching African art, found out about some Mexican artists’ connections with the Harlem Renaissance, and grew increasingly interested in Mexican muralism and printmaking.

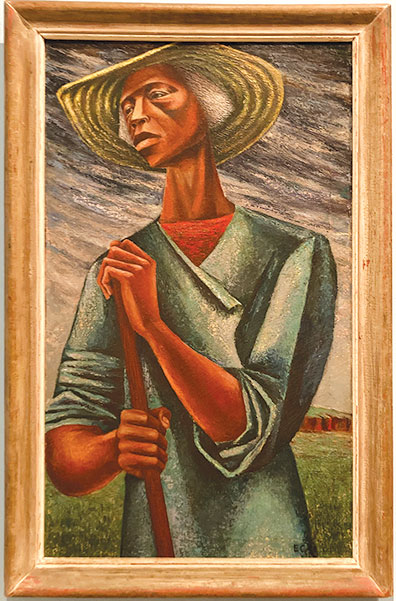

Sharecropper,

1946.

Sharecropper,

1946.It was also at Howard that a fellow student introduced her to socialist ideas. In December 1934, she joined other Howard students in a protest against lynching in which demonstrators wore nooses around their necks. Over subsequent years she became close to a broad range of the era’s most famous African American artists, writers and activists who were aligned with the Communist Party (CP), from singer and actor Paul Robeson, muralist Jacob Laurence and writer Lorraine Hansberry to innumerable others. In Depression-era U.S. society, Communists had taken the lead in key struggles against racist repression such as the case of the nine “Scottsboro Boys” targeted by lynch-law “justice” in Alabama. In important ways (despite the bureaucratic degeneration of the Soviet workers state under Stalin), this reflected the ongoing impact of the Russian Revolution of 1917.4

In 1936 Catlett moved to Durham, North Carolina, where she taught art at a high school, supervised art programs at several elementary schools and participated in protests demanding higher pay for teachers. After two years in Durham, she pursued graduate studies in art at the University of Iowa, where she studied with the “regionalist” artist Grant Wood, best known for his 1930 painting American Gothic. Wood, who encouraged his students to make art about “something you know the most about,” became a mentor to Catlett. Graduating in June 1940, Catlett became the first person in the U.S. to get a Master of Fine Arts degree. Over the next two years, she briefly chaired the art department at Dillard University in New Orleans – where even taking black students to a Picasso exhibit (at a museum in a segregated city park) meant “breaking the color bar” – and lived briefly in Chicago. There, she connected with artists and writers who were part of the “Black Chicago Renaissance,” including Gwendolyn Brooks, Frank Neil and CP member Charles White, whom she married in December 1941.

The following year, Catlett and White moved to Harlem and then Greenwich Village. In New York, they rubbed shoulders with everyone from Langston Hughes and Duke Ellington to Paul Robeson and W.E.B. Du Bois, and, in Catlett’s case, studying sculpture with Russian-born artist Ossip Zadkine, who was particularly influenced by African art. Over the next years Catlett’s connections in the CP milieu deepened, as she worked at Camp Wo-Chi-Ca (the Workers Children’s Camp), taught ceramics at the party’s Jefferson School and became staff artist for the publication of the CP-led National Negro Congress. Most importantly, she began working at the George Washington Carver School on 125th Street in Harlem.5

Established in 1943 under the leadership of poet and graphic artist Gwendolyn Bennett, the Carver School was an adult education center that taught a broad range of subjects including writing, art, black history, U.S. history, labor studies and “practical economics.” and other subjects. At the school, many of whose students were black women, Catlett did publicity and fundraising work and taught courses on sculpture, pottery, block printing and dressmaking. She later described the student body as consisting largely of “lower working-class people” including maids, garment trades workers, elevator operators and others. Decades later, Catlett recalled the Carver School being targeted by “a big red-baiting article” in the New York Herald Tribune branding the Carver School as “a Red Front school.”6 In 1947, as the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) revved up its anticommunist hearings, Democratic president Harry Truman issued an executive order directing the Department of Justice to assemble a list of “subversive” organizations. The Carver School was included on the list and soon shut down.

In Mexican Exile, An Artistic/Political Convergence

However, Elizabeth Catlett’s experiences w ith the working-class students at the Carver School had a major, long-lasting effect on her work. One of the ways this was reflected at the Brooklyn Museum exhibit was in its display of 16 linocuts from her The Black Woman series from 1946-47. These powerful images focus not only on Harriet Tubman and other historical figures who led black people to emancipation, but also on the arduous labor of women workers “In the Fields,” “In Other Folks’ Homes” and elsewhere, together with scenes of repression and segregation. This links up with many of the works Catlett would soon be creating in Mexico, including some like Campesinos Mexicanos (1947), in which tools, the design of farm laborers’ straw hats and other motifs draw parallels to sharecroppers’ toil in the U.S. South.

In these and other works at the exhibition, the history of slavery and the seizure of indigenous land looms as the background to ruthless exploitation in the present day, bringing to mind the famous passage on “primitive [i.e., original] accumulation” in Karl Marx’s Capital:

“The discovery of gold and silver in America, the extirpation, enslavement and entombment in mines of the aboriginal population, the beginning of the conquest and looting of the East Indies, the turning of Africa into a warren for the commercial hunting of black skins, signalized the rosy dawn of the era of capitalist production.”

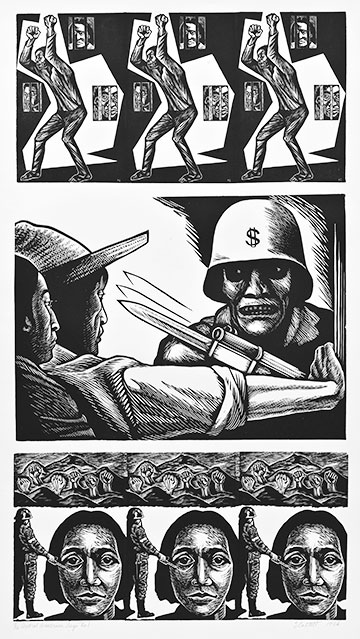

Linocut Central

America

Says No! (1986), denouncing murderous repression

unleashed by U.S. imperialism against revolutionary

upheavals that broke out in the region in the late 1970s and

1980s. Click on image to enlarge.

Linocut Central

America

Says No! (1986), denouncing murderous repression

unleashed by U.S. imperialism against revolutionary

upheavals that broke out in the region in the late 1970s and

1980s. Click on image to enlarge.

Catlett frequently highlighted this shared scar of primitive accumulation and the following history of subjugation and exploitation under capitalism experienced by both black American and Mexican workers. Similar themes were explored by another “transnational” artist closely connected to the CP, Hungarian-born Hugo Gellert, who in 1934 published a great series of prints called Karl Marx’ “Capital” in Lithographs. (See illustration.)

With the Cold War increasingly strangling artistic, intellectual and political life in the U.S., with African Americans like Robeson, Du Bois and innumerable others among those smeared and targeted, many sought relief from U.S. racism and rightist reaction by moving abroad. Quite a few major cultural figures, such as James Baldwin, Richard Wright, Chester Himes and Bud Powell, moved to Paris. During the same period, many black and white activists, artists, writers and film makers from the U.S. Communist milieu moved to Mexico. After receiving a foundation grant to study in Mexico, Elizabeth Catlett moved there in mid-1946. Over time, she came to refer to African Americans and the people of Mexico as her “two peoples,” highlighting shared legacies and connections and seeking to draw them closer together.

Catlett reached an artistic/political confluence or convergence when she became connected with the artists of the Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP – People’s Graphic Arts Workshop), a group of radical print makers, many of whom were Communists. (Among its members was Francisco Mora, whom Catlett married in 1947 after divorcing Charles White.) As Catlett herself put it, “We were concerned not only with problems in Mexico; the problems of whatever oppressed people, colonial or semicolonial, were of concern to us.”7 The TGP specialized in inexpensive or free linocut prints focused on labor and peasant (campesino) struggles, Mexican revolutionary history, solidarity with anti-imperialist movements, particularly in Latin America. Many of these prints still have a powerful attraction today, while others, especially on “antiwar” themes, seem frankly tame, reflecting the fact that Mexican CP followed the Soviet bureaucracy’s Quixotic quest for “peaceful coexistence” with U.S. imperialism.

Unfortunately, U.S. imperialism’s Cold War offensive, which by the 1950s was bringing death and destruction to workers and peasants from Korea to Iran, southern Africa to Central America, hit Mexico as well. Anti-communist U.S. “labor leaders” worked with the CIA and the Mexican government to purge leftist unionists in Mexico. Surveillance of Catlett and other expatriate U.S. leftists by the FBI intensified, likely spurred in part by the TGP’s 1953-54 print series Against Discrimination in the U.S., which included portraits of Robeson, Du Bois, Douglass, anti-lynching and black self-defense advocate Ida B. Wells, pioneering black trade unionist Isaac Myers (titled Unity of All Workers) and others. Catlett’s husband contributed a portrait titled Mississippi Ballot, of former slave Blanche Bruce, who during Radical Reconstruction became a U.S. senator.

Unbowed and Unsilenced

In 1958, the Mexican government viciously targeted dissident teachers and militant railroad workers, sending CP-aligned union leaders to prison on charges of “social dissolution.” (Still imprisoned a decade later, the fight for their freedom was one of the touchstones of the 1968 Mexican student movement.) At the same time, the Mexican authorities, with encouragement from the U.S. embassy, rounded up a number of leftists who had moved to Mexico from the United States, together with refugees from the Franco dictatorship in Spain, the Batista dictatorship in Cuba, the military junta installed in Guatemala by the U.S.-organized 1954 coup there, and others. Elizabeth Catlett was violently seized at her home and thrown in jail, later stating that she was freed only through the personal intervention of Mexico’s Secretary of Education, who was an admirer and collector of her artwork.

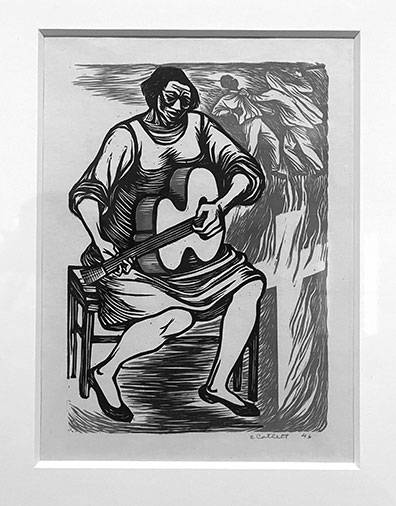

“I Have

Given the World My Songs,” 1947,

“I Have

Given the World My Songs,” 1947,from the series The Negro Woman.

Seeking to avoid further threats of deportation, Catlett decided to apply for citizenship in Mexico, which granted it to her in 1962. With the United States under John F. Kennedy seeking to root out “communist subversion” throughout the Americas in the wake of the Cuban Revolution, the United States government labeled Catlett an “undesirable alien” and she was banned from returning to the U.S. Yet amidst the growth of black freedom movements in the 1960s and early ’70s, her work was increasingly known and popular among African American activists and art aficionados. Repeatedly invited to conferences as well as exhibitions of her work, she was repeatedly denied a visa.

In 1969, scheduled to give the keynote address to a major conference on black art at Illinois’ Northwestern University, she had to give the speech by phone from Mexico because the U.S. embassy would not allow her in. It was only in 1971, a decade after her last trip to the U.S., that she finally got a visa to travel there, to attend the opening of her solo exhibition Elizabeth Catlett: Prints and Sculpture at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Yet it was not until 2002 that the U.S. reinstated her citizenship. In 2010, at the age of 94, she presented her sculpture of singer Mahalia Jackson in New Orleans. Two years later, in April 2012, Elizabeth Catlett died at her studio/home in Cuernavaca.8

To get a sense of what she must have been like as a person, here is how, in the speech she gave by phone from Mexico in 1969, she addressed the issue of why the U.S. government had denied her a visa to visit the country of her birth:

“Unfortunately for me, I was refused on the grounds that, as a foreigner, there was a possibility that I would interfere in social or political problems, and thus I constituted a threat to the well-being of the United States. To the degree and in the proportion that the United States constitutes a threat to black people, to that degree and more, do I hope to have earned that honor. For I have been, and am currently, and always hope to be a Black Revolutionary Artist and all that it implies!”

So we found a kindred spirit in our visit to the Brooklyn Museum exhibition, at a time when all our hard-won rights are under attack. For her inspiring art and her defiant courage in the face of racist reaction, we embrace the memory of Elizabeth Catlett. ■

- 1. “Black and Red Keys to Harlem Renaissance Story” and “Elizabeth Catlett (1915-2012),” Revolution No. 21, September 2024.

- 2. This is reproduced in the abovementioned short article on Catlett in Revolution No. 21.

- 3. See Rebecca M. Schreiber, Cold War Exiles in Mexico (2008), which includes several sections on Catlett.

- 4. See James P. Cannon, “The Russian Revolution and the American Negro Movement” (1959), published as a pamphlet by the Internationalist Group.

- 5. Rashieda Witter, “Chronology,” in Dalila Scruggs (editor), Elizabeth Catlett: A Black Revolutionary Artist and All That It Implies (2025).

- 6. Patricia Hills, interview with Elizabeth Catlett, 3 June 1995, Boston University (OpenBu). The Herald Tribune article in question seems to be “Communists and the Negro Problem,” 23 December 1943, which quotes NAACP president Walter White attacking the school; further coverage followed in the New York Times and other papers.

- 7. Melanie Anne Herzog, Elizabeth Catlett: An American Artist in Mexico (2005).

- 8. Witter, “Chronology.”