September 2024

What We Saw

– and Didn't – at Important Met Exhibit

Black and Red Keys to

Harlem Renaissance Story

“From Slavery Through Reconstruction” (1934) by Aaron Douglas, part of his mural cycle, Aspects of Negro Life, commissioned by the Works Progress Administration for the Countee Cullen branch of the New York Public Library. Click on image to enlarge. (Photo: Aaron Douglas, Anna-Marie Kellen / Courtesy The Met)

By Yalina, Roser and Ray

This summer, activists from the Internationalist Clubs at the City University of New York and the Revolutionary Internationalist Youth visited the “Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism” exhibit at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. It was exhilarating to see the incredible art in the exhibit, which showcased around 160 works. But we were disappointed by some of its glaring omissions. The whole group of comrades who went there wound up discussing and debating the inspiring aspects of the exhibit, but also the way the museum’s presentation of it left so much of the “red” – the radical political connections and reverberations of the Harlem Renaissance – out of the picture.

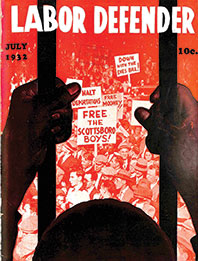

Magazine of CP’s legal defense arm, the

International Labor Defense (founded in 1925 under the

leadership of James P. Cannon), building campaign to free

the nine African American youth condemned to death in

Scottsboro frame-up.”

Magazine of CP’s legal defense arm, the

International Labor Defense (founded in 1925 under the

leadership of James P. Cannon), building campaign to free

the nine African American youth condemned to death in

Scottsboro frame-up.” As we often point out in Revolution, learning about history is vital for revolutionaries – and art can tell us a lot about it. What artists choose to portray, and how, can tell us quite a bit about society and its changes. One good example is the explosion of artistic creativity and innovation in the first years of the Russian Revolution. Another is the upsurge in African American poetry, painting, sculpture, music, dance – and politics – known as the Harlem Renaissance, which made household names of poets and painters such as Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston and Jacob Lawrence. Rooted in resistance to “Jim Crow,” America’s system of violent racial segregation, it drew power and inspiration from the restless and rebellious black population undergoing big changes in the early 20th century.

Roots of Rebellion in Jim Crow America

Up until then the African American population was concentrated in the rural South; the Harlem Renaissance was fueled by the “Great Migration” northward. Depicted in Lawrence’s stunning Migration Series, this was the movement of millions of black people out of the South, seeking escape from desperate poverty, the sharecropping system, Ku Klux Klan terror and pervasive segregation. With World War One, in which the U.S. seized its place as the dominant imperialist power, labor shortages in the North drew large numbers to jobs there. Just between the years 1915 and 1918, an estimated 500,000 African Americans moved north and one of their main destinations was New York. Here, in Harlem, the stories, speech, music and dance of black working people became the “motive forces of the cultural awakening” expressed in the Harlem Renaissance.1

During World War I, 380,000 black men served in the segregated U.S. Army WWI – but the “land of the free” only permitted one in ten any combat role. When they came home from a war promoted as one to supposedly “make the world safe for democracy,” they faced a wave of racist backlash “up North” as well as down South. Many were among the newly urbanized African Americans that were becoming increasingly politicized, and in many cases radicalized, particularly after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia led by the Bolsheviks, who appealed to oppressed and subjugated peoples– including African Americans – to join forces in the worldwide revolutionary struggle.

Viewing portrait of

Langston Hughes (1925), a giant of the Harlem Renaissance,

by German immigrant artist Winold Reiss. (Revolution photo)

Viewing portrait of

Langston Hughes (1925), a giant of the Harlem Renaissance,

by German immigrant artist Winold Reiss. (Revolution photo)Exactly when the Harlem Renaissance began is debated by historians, with some citing a key musical revue in 1921, a poetry anthology edited by James Weldon Johnson the following year or Jean Toomer’s novel Cane (1923). Alain Locke’s crucial anthology The New Negro came out in 1925. So did a special issue of Survey Graphic magazine – displayed at the Met exhibit – titled “Harlem, Mecca of the New Negro,” with portraits by Winold Reiss, poems by Hughes, Countee Cullen and Claude McKay, and many intriguing articles.2 Also shown at the Met exhibition was the literary magazine that Cullen, Hughes, Hurston, Gwendolyn Bennett, Bruce Nugent, Wallace Thurman and others started in 1926, called Fire!! With a cover by Aaron Douglas, only one issue came out, but it had a big impact, and Fire!! is considered a milestone.

"If We Must Die” and Black Liberation

Before all of these vital developments, however, came 1919, the year many historians point to as the seminal year for the Renaissance. It was then that the movement’s most famous poem came out: McKay’s “If We Must Die” (see box below). Advocating black self-defense against the violent white mobs that attacked many black neighborhoods across the country that summer, the poem had an electrifying effect.

Claude McKay speaking at

the Fourth Congress of the Comintern, Moscow, November 1922.

(Photo: Marxists Internet

Archive)

Claude McKay speaking at

the Fourth Congress of the Comintern, Moscow, November 1922.

(Photo: Marxists Internet

Archive)Claude McKay would, like Langston Hughes, become one of the

black, red – and gay – icons of the Harlem Renaissance whose

work speaks powerfully to us today. He would later travel to

Soviet Russia, headquarters of the Communist International

(Comintern), which was also founded in 1919 in the wake of

the Bolshevik Revolution. There, he would meet with Lenin,

Trotsky, Clara Zetkin and other leaders of the new

international and give a crucial report on the fight for

black liberation at the Comintern’s Fourth Congress in 1922.3

The Met exhibit’s lushly illustrated 332-page catalogue book, The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism, does include valuable material. Despite the academic lingo, an essay on “gay sociability” in Harlem during that period discusses the cosmopolitan connections and broad influence of Alain Locke (who called himself the “midwife” to the movement), Bruce Nugent, Richmond Barthé and other gay Harlem Renaissance protagonists. Another, titled “A Political Pageant: The Harlem Renaissance on Parade,” manages to say nothing at all about leftist radicalism.

Nor is communism mentioned in the rest of the book, with the exception of two short paragraphs in the essay “Harlem and the Dutch Caribbean” mentioning Harlem activists Otto Huiswood, who went to the 1922 Comintern congress with McKay, and Cyril Briggs. Huiswood and Briggs had been part of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) of Marcus Garvey. McKay and Garvey were originally from Jamaica, Briggs was born on the Caribbean island of Nevis and Huiswood was from Dutch Guiana (now Surinam) – an indication of the major role of immigrant activists in political/cultural life.

Garveyism’s promotion of black pride had gained it a mass following in those years. Yet it did not challenge the racist capitalist system nor seek allies in struggle from other oppressed and exploited sectors of society, instead promoting the fantasy of going “back to Africa.” Garvey even met with the top leader of the KKK in 1922 on the basis that the hooded night-riders were also supporters of racial separation. Forming a left opposition to Garveyism, both Briggs and Huiswood (together with Jamaican immigrant W.A. Domingo and others) were founders of the African Blood Brotherhood, which, in its militant advocacy of black self-defense, echoed McKay’s “If We Must Die.”

Lenin and Trotsky’s insistence on the centrality of black liberation to revolutionary struggle was a crucial part of bringing the lessons of the Russian Revolution to U.S. socialists who, heeding the call of the Comintern, sought to break decisively from social-democratic reformism.4 Rejecting separatism and embracing a class-struggle standpoint in the fight for black freedom, Briggs, Huiswood and several of their co-thinkers became some of the crucial early black cadre of the Communist Party in the U.S., which was founded in 1919. The CP became a major force in antiracist struggles during the Great Depression, even after the rise of Stalinism, with its anti-Marxist dogma of “socialism in one country,” blunted and then buried its revolutionary program.

Two Poems of the Harlem Renaissance

| First published in July 1919 in

the left-wing socialist magazine The Liberator, Claude McKay’s “If We Must Die” raised the call for black self-defense against the wave of attacks by white racist mobs after World War One. Langston Hughes’ “White Man,” was first published in the New Masses, a magazine that was closely associated with the Communist Party, in December 1936. (The previous year, as referred to in the poem, Italy had invaded and occupied Ethiopia.) “If We Must Die,”

|

“White Man,”

|

Haunted By the Spectre of Communism

This history too is a part of our radical heritage, intertwined with the story of the Harlem Renaissance. The relation between its volcanic artistic creativity and the revolutionary aspirations of so many of its protagonists, between the fight for black liberation and socialist revolution – between black and red – all this is crucial to understanding its meaning.

Visiting the exhibit, it felt like the famous “spectre of communism” was haunting the Met but kept eerily invisible and unmentioned by its curators. The work of Aaron Douglas was showcased there in large breathtaking paintings like Aspiration, Judgment Day, Let My People Go and Aspects of Negro Life: From Slavery to Reconstruction, as well as portraits like Scottsboro Boys. The exhibit included a glorious oil painting by Elizabeth Catlett and Winold Reiss’ portraits of Hughes, W.E.B. Du Bois, Paul Robeson and other towering figures. Yet the exhibit noted nothing about their relation to leftist radicalism, and amidst thousands of words posted on the walls, the word communist wasn’t present at all – even in the section titled “The Artist as Activist.”

To get a sense of how much red got bleached out of the picture, consider the people mentioned in the previous paragraph: Aaron Douglas, whose work is filled with allusions to radical themes, joined the Communist Party in the early ’30s. Elizabeth Catlett lived for many years in Mexico (see box below) but was prevented from moving back to the U.S. – because of her closeness to the CP. Winold Reiss, the German immigrant often described as Douglas’ mentor, was a radical anti-racist clearly influenced by the Communist movement. Langston Hughes, the Renaissance’s foremost literary figure, wrote innumerable poems proudly advocating Communist views, such as “Ballads of Lenin,” “Goodbye Christ,” “Good Morning Revolution” and “White Man” (see box titled "Two Poems of the Harlem Renaissance," above).5 W.E.B. Du Bois, NAACP founder, author of Black Reconstruction, The Souls of Black Folk and other historic works, joined the CP at the age of 93. Paul Robeson, the incomparable singer, actor, director, athlete and activist – Renaissance man of the Harlem Renaissance – was a key figure of 20th-century radicalism, closely associated with the CP throughout his life.

Langston Hughes speaking in Paris,

January 1938, after spending four months in Spain during the

civil war.

Langston Hughes speaking in Paris,

January 1938, after spending four months in Spain during the

civil war. (Photo: Archives at Queens Library)

That there wasn’t a whisper of this at the Met frankly made us kind of mad – especially since anti-communists tried to silence almost all of them and so many others because of their politics. When the witch hunts escalated after WWII, virtually any opposition to the racist status quo was stigmatized as “red.” It’s a badge of honor that almost all the leftist trailblazers of the Harlem Renaissance wound up being targeted by the notorious HUAC (House Un-American Activities Committee). The fact – rarely referred to today – is that HUAC and other red-baiting outfits destroyed the careers, and sometimes the lives, of innumerable black artists, writers, actors, musicians and scholars.6

Former Fire!! co-editor Gwendolyn Bennett – a poet who studied art with Aaron Douglas and also worked as a teacher with Elizabeth Catlett – was one of them. “Investigated” for 18 years by the FBI, in the ’40s she was targeted by HUAC, leading to her suspension as director of the Harlem Community Arts Center and, in 1947, the closing down of Harlem’s George Carver Community School, an adult education center she helped establish. Most of Bennett’s artwork was destroyed in a fire; her contributions were largely forgotten. The exhibit’s own “forgetting” reminds that to unearth our history does have “subversive” implications.

In its own way, the issue of communism and anti-communism is also posed by Miss Zora Neale Hurston (1926), another portrait by Aaron Douglas shown at the exhibit. Today, Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God is a staple of literature courses. In 1937, when the novel came out, a famous controversy erupted between Hurston and Richard Wright, then one of the foremost CP-aligned literary figures. In his review of the book in New Masses (5 October 1937), Wright accused it of pandering to white readers with “chauvinistic tastes.” Hurston hit back with an attack on Wright’s Uncle Tom’s Children (1938), saying his book featured “lavish killing … perhaps enough to satisfy all male black readers,” while presenting “the picture of the South that the communists have been passing around.” Wright, she added, advocated “the solution of the PARTY – state responsibility for everything and individual responsibility for nothing” (capitalization in original). During McCarthyism, Hurston went on to escalate her red-baiting of “commies,” in the magazine of the American Legion.

Fighting the Racist “Justice” System

In 1932, Langston Hughes, along with twenty-two other African American artists and activists, visited the Soviet Union to assist in the creation of a Soviet film, Black and White, intended to depict and expose American racism.7 The film was never made but Hughes toured the Soviet Union and wrote about what he saw in his pamphlet A Negro Looks at Soviet Central Asia (1934). In the U.S. during that same period, the CP took up the case of nine black youths known as the “Scottsboro Boys.” Framed up on false charges of raping two white women on a freight train in Alabama, they faced both lynching threats and “legal lynching” through the racist death penalty.

This

was one of the favorite paintings Internationalist Club

comrades saw during our visit to the Met exhibit: The

Janitor Who Paints (circa 1937, repainted after 1940)

by Palmer Hayden. In a 1969 interview, Hayden explained that

the artist he had depicted was an older African American man,

Cloyd Benkin, who supported himself as a janitor. Click on

image to enlarge. (Revolution photo)

This

was one of the favorite paintings Internationalist Club

comrades saw during our visit to the Met exhibit: The

Janitor Who Paints (circa 1937, repainted after 1940)

by Palmer Hayden. In a 1969 interview, Hayden explained that

the artist he had depicted was an older African American man,

Cloyd Benkin, who supported himself as a janitor. Click on

image to enlarge. (Revolution photo)Mass support for the Scottsboro 9 was organized by the CP’s legal defense arm, the International Labor Defense. (Under the leadership of James P. Cannon – who subsequently founded the U.S. Trotskyist movement – the ILD had organized the Sacco and Vanzetti campaign in defense of immigrant anarchists executed on frame-up charges in 1927.) Through the ILD’s tireless, racially integrated activism, the Scottsboro 9 became a cause célèbre in the U.S. and internationally. Among the many Harlem Renaissance figures who contributed their talents to the cause was Langston Hughes, who in 1932 came out with a volume titled Scottsboro Limited, containing a play in verse and four of his poems. The first reads: “That Justice is a blind goddess / Is a thing to which we black are wise / Her bandage hides two festering sores / That once perhaps were eyes.”

The defense campaign helped save the lives of the Scottsboro defendants – though the racist authorities kept them in prison for many years. Many black activists, workers and intellectuals joined the party through the campaign. Aaron Douglas’ pastel on paper drawing “Scottsboro Boys” (1935), a striking portrait of defendants Clarence Norris and Haywood Patterson, is included in the Met’s Harlem Renaissance exhibit (though again, no mention is made of communists’ involvement).

Cultural expressions like art and literature, which help us experience and understand the world, have also been important ways in which revolutionaries have communicated and immortalized social conditions, attitudes, political ideas as well as leaders and activists in the struggle for liberation.

Lastly, in light of the red and black history of the Harlem Renaissance, what might its radical founders have made of the claims being sold to us today? For example, that faced with a government of war abroad and police terror at home, we should “pray for peace” and vote “VP Top Cop” for “Prosecutor-In-Chief,” that is, for president?

Here, too, we will turn to Langston Hughes. His 1949 poem “Who But the Lord?” goes like this:

“I looked and I sawOr as we’ve been saying: only revolution can bring justice. ■

That man they call the Law.

He was coming

Down the street at me!

I had visions in my head

Of being laid out cold and dead,

Or else murdered

By the third degree.

“I said, O, Lord, if you can,

Save me from that man!

Don’t let him make a pulp out of me!

But that Lord he was not quick.

The Law raised up his stick

And beat the living hell

Out of me!

“Now, I do not understand

Why God don’t protect a man

From police brutality.

Being poor and black,

I’ve no weapon to strike back

So who but the Lord

Can protect me?

“We’ll see.”

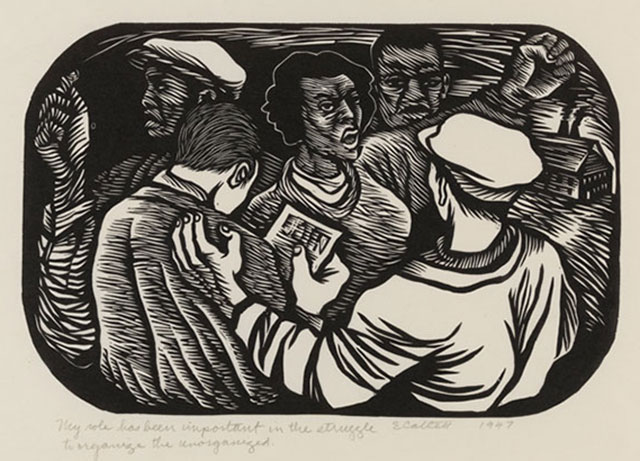

Elizabeth Catlett (1915-2012)

(Photo: © Mora-Catlett Family)

By Alyssa

In the Met’s “Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism” exhibit, graphic artist and sculptor Elizabeth Catlett was represented by an oil painting from the early 1940s, “Head of a Woman.” All her life, Catlett was a radical artist, committed to black liberation and the cause of the laboring classes in the U.S., Mexico (where she lived for many years) and around the world. Reprinted here is a linocut by her that the Hunter Internationalist Club incorporated into our flier for the great International Women’s Day forum featured in the last issue of Revolution (No. 20, September 2023).

Like Paul Robeson and other Harlem Renaissance personalities, Elizabeth Catlett was the grandchild of slaves. Born in Washington, D.C., she was admitted to the Carnegie Institute of Technology but refused entry when the administration found out she was black. After getting her bachelor’s degree at Howard University, she earned an MFA at the University of Iowa and then moved to Chicago. There, she intersected a dynamic African American arts scene in which many artists supported the Communist Party. Subsequently moving to New York City, she became a friend of Langston Hughes, W.E.B. Du Bois, Paul Robeson and Jacob Lawrence.

All the while, Catlett created paintings, engravings, sculptures in stone and wood, almost all of them advancing social themes – in particular the struggles of African American women, famously portraying Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth and Phyllis Wheatley. As noted in the article (see above), Catlett was among those targeted by the FBI and House Un-American Activities Committee, as a result of which she lost her important positions as an educator in NYC. In 1949 she moved to Mexico, where she met leading painters, including Miguel Covarrubias, who had illustrated Langston Hughes’ first book of verse, The Weary Blues (1926). Catlett joined the widely influential art collective to which Covarrubias belonged, the Taller Gráfica Popular (People’s Graphic Workshop), and also worked and apprenticed with muralist Diego Rivera. “We were concerned not only with problems in Mexico; the problems of whatever oppressed people, colonial or semicolonial, were of concern to us,” Catlett later recalled (Melanie Herzog, Elizabeth Catlett, An American Artist in Mexico [2005]).

Like her Taller colleagues, many of whom were Communists, Catlett joined in the struggles of the Mexican workers and was even arrested for participating in the historic railway workers strike of 1958. Teaching sculpture at Mexico’s National University (UNAM), the great African American artist became a Mexican citizen in 1962. With the U.S. embassy in Mexico classifying her an “undesirable alien,” she found herself barred from re-entry to the land of her birth. When fellow artists in Mexico awarded a prize to her linoleum block print “Malcolm X Speaks for Us,” she observed: “I am inspired by black people and Mexican people, my two peoples” (“My Art Speaks for Both My Peoples,” Ebony, January 1970). Elizabeth Catlett lived on, working and teaching almost to her death in 2012, at the age of 96. For young revolutionaries, her artwork speaks to us and her radical life is an inspiration.

Editors’ note: Work on this article was underway when we learned the exciting news that Brooklyn Museum will be presenting an exhibit titled “Elizabeth Catlett: A Black Revolutionary Artist and All That It Implies” 13 September 2024 – 19 January 2025. CUNY Internationalist Clubs supporters and friends are invited to go see it with us (write cunyinternationalists@gmail.com)!

- 1. Eric Arnesen, Black Protest and the Great Migration (2003); Cheryl Wall, The Harlem Renaissance (2016).

- 2. The wide-ranging issue included James Weldon Johnson’s “The Making of Harlem”; “Black Workers and the City” by Charles S. Johnson; “The Tropics in New York” by W.A. Domingo”; “The Double Task: The Struggle of Negro Women for Sex and Race Emancipation” by Elise Johnson McDougald; Arthur Schomburg on the growing interest in black history; items by then-leaders of the NAACP W.E.B. Du Bois and Walter White, and others.

- 3. See The Communist International and Black Liberation, Internationalist pamphlet, 2005.

- 4. See James P. Cannon’s “The Russian Revolution and the American Negro Movement” (1959), available as an Internationalist pamphlet.

- 5. Less known is his poem “October 16: The Raid” (1931), which begins: “Perhaps you will remember John Brown, who took his gun, took twenty-one companions, white and black…” and evokes the “immortal raiders” whose 1859 attack on the Harpers Ferry armory foreshadowed the Civil War. Among the raiders who died there was African American leatherworker Lewis Sheridan Leary. Leary’s widow Mary married Ohio abolitionist Charles Langston – their daughter Caroline was the mother of Langston Hughes.

- 6. “In the McCarthy Era, to Be Black Was to Be Red,” JSTOR Daily, 13 November 2019. This is the subject of the powerful documentary “Scandalize My Name: Stories from the Blacklist” (1998).

- 7. “When the Harlem Renaissance Went to Communist Moscow,” New York Times, 21 August 2017.