June 2023

Esteban Volkov Fought to Uphold Trotsky’s Revolutionary Legacy

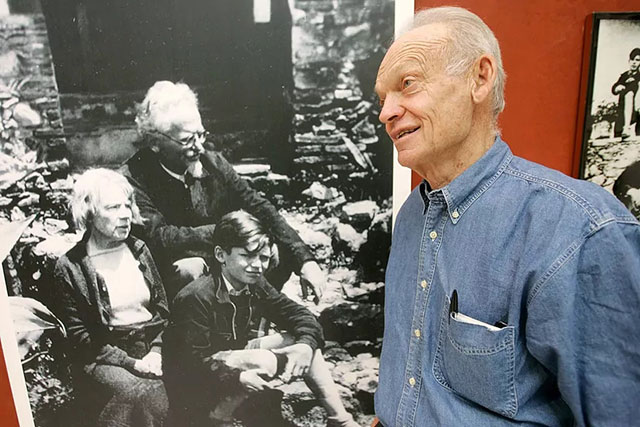

Esteban Volkov, grandson of Leon Trotsky, in front of photo of him as a youth together with Trotsky and Natalia Sedova on display at the Museo Casa de León Trotsky in Coyoacán, Mexico City. (Photo: Reuters)

The following obituary of Leon Trotsky’s grandson Esteban Volkov was published by the Washington Post on 22 June 2023. It is rare that a major bourgeois newspaper gives a reasonably accurate account of a prominent figure who dedicated his life to keeping the flame of revolution burning.1 Of course, this account barely touches on Trotsky’s role together with Lenin in leading the 1917 October Revolution, and leaves unmentioned his founding and leading of the Red Army in the ensuing Russian Civil War, as well as his struggle to build the Fourth International. Nevertheless, the author did a conscientious job in researching and portraying Esteban’s life and achievement, notably in turning Trotsky’s home in Coyoacán into a vibrant museum portraying the Bolshevik leader’s fight to carry forward the internationalist program of Red October. The founders of the League for the Fourth International worked with Esteban in supporting his efforts to preserve and maintain the Trotsky home (including the funeral monument) and its transformation into a museum, and counted him as a friend and revolutionary comrade.

Following this obituary, we reprint a speech by Esteban Volkov at Trotsky’s grave in August 2009 on the 69th anniversary of his assassination.

Esteban

Volkov, Trotsky’s Grandson

and Keeper of His Flame, Dies at 97

He preserved the memory of his grandfather through a museum he started in a suburb of Mexico City — in the home where his grandfather was assassinated

By Phil Davison

Esteban Volkov, who witnessed the dying breaths of his grandfather, Leon Trotsky – the exiled Russian revolutionary leader whose assassination in Mexico in 1940 had been ordered by archrival Joseph Stalin – and who devoted his final decades to preserving Trotsky’s legacy, died June 16 in Tepoztlán, Mexico.

He was 97 and had lived in the Mexico City suburb of Coyoacán since coming under the guardianship of Trotsky at age 13. His daughter Nora Volkow, who uses a different spelling of the family name, confirmed the death but did not provide a specific cause. She said her father became blind earlier this year and entered a nursing home in Tepoztlán, a town south of the capital.

Esteban with his grandparents on

a rare outing, to Taxco, Guerrero in 1939.

Esteban with his grandparents on

a rare outing, to Taxco, Guerrero in 1939. Mr. Volkov was a retired chemical engineer when, in 1990, he opened a museum in the house on Calle Viena where he had lived with his grandfather. The timing of the museum coincided with the end of the Cold War and a year before the collapse of the Soviet state that Trotsky, along with Vladimir Lenin, had helped create.

The purpose of the exhibition space was to bring renewed attention to the man whom Stalin had sent into exile amid a power struggle to lead the Soviet Union after Lenin’s death in 1924. Stalin painted Trotsky as a subversive and tried to erase him from Soviet history.

“We don’t ask for political rehabilitation because he doesn’t need political rehabilitation,” Mr. Volkov told the Los Angeles Times of his grandfather, who was granted asylum by Mexico’s left-wing president and moved there in 1937. “We want historical truth. … Truth is a basic element of progress. We cannot go anywhere without the truth.”

The Leon Trotsky House Museum is now run by the Mexican state and has more than 50,000 visitors annually.

Trotsky warned his grandson to stay out of politics for his own safety, and he obeyed. The museum is not meant to serve as a temple to his grandfather’s politics but to elaborate on the political journey of a man who had been born Lev Davidovich Bronstein and came from a wealthy Jewish family.

Mr. Volkov was born Vsevolod Volkov Platonovich Bronstein on March 7, 1926, in Yalta on the Crimea peninsula that had been part of the Russian empire and remained so under the Soviets. After Ukraine gained its independence from the shattered Soviet Union in 1991, Crimea became part of Ukraine and still is, although it has been occupied by invading Russian forces since 2014.2

Mr. Volkov’s mother, Zinaida, was one of Trotsky’s two daughters. Mr. Volkov’s father, Platon Volkov, was a Trotsky supporter who was later arrested and disappeared into Stalin’s prisons, reputedly murdered by the regime.

Zinaida was allowed to leave the Soviet Union with her son, then 5 years old, to visit her father, who had been exiled to an island in the Sea of Marmara near Istanbul. For reasons that only became clear to Mr. Volkov decades later, his slightly older half-sister, Aleksandra, was left behind — not to be seen again by him for 57 years.

In 1932, fearing for the safety of his daughter and grandson, Trotsky told them to go to Berlin. Within a few weeks, Zinaida fell ill with tuberculosis. Grief-stricken and suffering from depression, she killed herself, according to her son, by leaving her head close to an unlit gas oven in their apartment.

Friends sent the child to a school in the Austrian capital, Vienna, run by self-styled “disciples” of psychiatrist Sigmund Freud, before his uncle Lev Sedov took him to Paris in 1934. Four years later, Sedov was found dead in a Paris hospital while being treated for appendicitis, with many historians concurring he had been poisoned by Stalinist agents.

Mr. Volkov later reckoned that, in all, 30 of his relatives were killed or disappeared by Stalin’s regime or, like his mother, took their own lives. He was soon sent to Mexico to join his grandfather, who called him Esteban in the Spanish-speaking country.

Although he was a world away from Europe, Mr. Volkov was not entirely safe. In May 1940, he was shot in the foot during an attempt to kill Trotsky in his home. Gunmen, reportedly led by Mexican muralist and Stalinist sympathizer David Alfaro Siqueiros, broke through the security team and riddled Trotsky’s bedroom with bullets from automatic weapons.

Trotsky’s wife pushed her husband into a corner, and they both survived. But the gunmen then fired into the neighboring bedroom, where young Mr. Volkov had been sleeping. “I was very, very lucky,” he recalled in a 2012 interview with the Spanish newspaper El País. “A gunman shot six times into my mattress, but I’d jumped under the bed. I remember the terrible noise and the smell of gunpowder.”

Some of the bullet holes

in the walls of the house from the failed assassination

attempt in May 1940 when the Stalinist painter David Alfaro

Siqueiros led a hit squad with a large calibre machine gun.

Three months later a lone assassin on Stalin’s orders

succeeded in murdering the co-leader together with Lenin of

the 1917 October Revolution. In the 1970s Stalinists in the

National Institute of Anthropology sought to cover up the

holes. (Photo: México

Desconocido)

Some of the bullet holes

in the walls of the house from the failed assassination

attempt in May 1940 when the Stalinist painter David Alfaro

Siqueiros led a hit squad with a large calibre machine gun.

Three months later a lone assassin on Stalin’s orders

succeeded in murdering the co-leader together with Lenin of

the 1917 October Revolution. In the 1970s Stalinists in the

National Institute of Anthropology sought to cover up the

holes. (Photo: México

Desconocido)Just months later, on Aug. 20, Mr. Volkov had returned home from school when he saw Trotsky bleeding to death but still standing defiantly in the arms of his bodyguards and his wife, Natalia Sedova.

“Keep the boy away. He shouldn’t see this!” he recalled his grandfather shouting.

The assailant, Spanish-born Stalinist Ramón Mercader, had found his way into the home under a pretense of being an admirer, then attacked Trotsky with a mountaineering ice-axe he had hidden in his coat.

Mr. Volkov saw his grandfather’s bloodied body taken away on a stretcher. Trotsky, who with Lenin had helped overthrow the Russian Empire during the 1917 Bolshevik revolution, died of his wounds the following day at age 60.

Mercader was convicted and spent almost 20 years in a Mexican jail before moving to the Soviet Union, where he received a hero’s welcome. A friend of Cuban leader Fidel Castro, he died of lung cancer in Havana in 1978.

After the assassination, Trotsky’s second wife, Natalia, looked after Mr. Volkov throughout his teenage years. At the National Autonomous University of Mexico, he received a degree in chemical engineering. He got a job as a chemical engineer at the Mexican pharmaceutical company Syntex and, through his work in the synthesis of steroid hormones, was involved in the development of the contraceptive pill.

He was married to Palmira Fernandez from 1953 until her death in 1997. In addition to Nora, who is director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse in Bethesda, Md., survivors include three other daughters, Veronica, Patricia and Natalia; five grandchildren; and two grandchildren.

Mr. Volkov spent much of his life knowing little of the fate of his half sister, Aleksandra, until he received a call in the late-1980s from a French historian, Pierre Broué, telling him she was alive in Moscow but dying of cancer. Amid Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s policy of glasnost, or openness, Mr. Volkov was granted permission in 1988 to visit with Aleksandra.

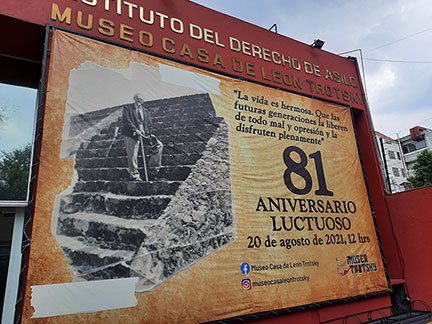

The Museo Casa de León Trosky on the occasion

of the 81st anniversary of his assassination in 2021. (Photo: Laura Camargo Fernández /

Twitter)

The Museo Casa de León Trosky on the occasion

of the 81st anniversary of his assassination in 2021. (Photo: Laura Camargo Fernández /

Twitter)“Aleksandra was always distressed that it was I who our mother took with her,” Mr. Volkov told the publication Workers Vanguard at the time. “It was [Pierre] Broué, who was first to find out why. Stalin had specified in the exit papers that she could only take her youngest child.” (Aleksandra also spent years in a labor camp in Kazakhstan, then a Soviet republic, as part of a roundup of people related to “enemies of the people.” She was freed after Stalin’s death in 1953.)

Mr. Volkov described his reunion with Aleksandra as bittersweet. They could barely communicate because he had forgotten his Russian, and she spoke no Spanish, English or French. Nevertheless, he said at a news conference, “it was a little like people from a shipwreck who meet safe and sound on the beach.”

Mr. Volkov also used the visit to press the Soviet state to clear the name of his vilified grandfather, whose very mention was taboo for decades. (He was never officially rehabilitated.)

Nora Volkow remembered her father as “an extraordinary man who infected me with his passion for science, justice and the truth, and who inspired me with his resilience. He liked nature, mountains, the ocean and loved music, with Shostakovich and Stravinsky his favorites. He never stopped walking and even died while walking, outside his nursing home.” ■

- 1. On Leon Trotsky’s assassination, the New York Times (22 August 1940) headlined its article “Trotsky Dies of His Wounds; Asks Revolution Go Forward,” but then added a subhead repeating the Stalinist lies spouted by his murderer: “Assassin Says He Broke With Victim After Exile Asked Him to Carry Out Acts of Sabotage in Russia.” Recognizing the threat to capitalist rule that Lenin’s comrade-in-arms represented, this was a continuation of the Times’ coverage during the infamous Moscow Frame-Up Trials of 1936-38. At the time, this semi-official voice of U.S. imperialism, through its Moscow correspondent Walter Duranty, regurgitated the Stalinist slanders against Bolshevik leaders including Nikolai Bukharin, Lev Kamenev, Grigorii Zinoviev, Yuri Pyatakov, Karl Radek and Trotsky, all of them killed on Stalin’s orders.

- 2. Crimea was historically part of Russia from 1783 until 1954 when Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev attached it to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. In 2014, following the imperialist-sponsored coup d’état in Kiev led by Ukrainian ultra-nationalists and fascists, the people of Crimea (more than three-quarters of whom listed Russian as their native language) voted overwhelmingly in a referendum to join the Russian Federation. The Kiev coup regime and its Western godfathers label this exercise of self-determination “Russian occupation” and vow to undo it by force of arms, ignoring the will of the Crimean population. The Washington Post, as one of the leading drumbeaters for war on Russia, naturally presents this distorted version.

August 2009

The Triumph of the Fourth International: The Duty and Task That Is Still to be Fulfilled

Speech by Esteban Volkov (Sieva)

on the 69th anniversary of the Assassination of Leon Trotsky

We publish below the words of Esteban Volkov (Sieva), the grandson of Leon Trotsky, on the anniversary of the death of the co-leader, together with Vladimir Lenin, of the October Revolution of 1917. His speech was given in front of the funeral monument designed by the Mexican muralist Juan O’Gorman in the garden of the Museo Casa de León Trotsky in Coyoacán, Mexico. This was where the great Russian and internationalist revolutionary lived the last years of his exile, before being assassinated by a Stalinist agent in August 1940. Among those who attended the ceremony were a dozen comrades of the League for the Fourth International. A spokeswoman for the Grupo Internacionalista, the Mexican section of the LFI, gave some brief remarks and at the end The Internationale was sung in Spanish, English, French and Russian.

Esteban

Volkov reading his speech commemorating the 69th anniversary

of the assassination of his grandfather, Leon Trotsky, in

front of the memorial stele by renowned Mexican artist Juan

O'Gorman at the museum in Coyoacán, Mexico City, August

2009. (Photo: El

Internacionalista)

Esteban

Volkov reading his speech commemorating the 69th anniversary

of the assassination of his grandfather, Leon Trotsky, in

front of the memorial stele by renowned Mexican artist Juan

O'Gorman at the museum in Coyoacán, Mexico City, August

2009. (Photo: El

Internacionalista)On August 20th, it will be 69 years since the day when on a hot summer afternoon, returning from school after a long walk to our house at Viena 19, in Coyoacán, I was able to see alive, for the last time, my grandfather, Lev Davidovitch, better known as Leon Trotsky.

It still seems to me as if it was yesterday, when on that afternoon, through a half-opened door of the library, I saw my grandfather, mortally wounded, lying on the kitchen floor with his head bloodied, and at his side his inseparable companion Natalia, who was applying ice to the head wound, attempting to stop the hemorrhaging. Also at his side, if I remember correctly, were the American comrades, Charlie Cornell and Joe Hansen.

Upon hearing my steps in the room next door, motioning in that direction, he said, “Keep Sieva away, he must not see this.” Shortly before, he had also admonished the comrades upon hearing the groans and cries of Stalin’s agent coming from his office where he was being beaten by one of the comrades: “Don’t kill him, he must talk,” were his words.

By the time he was in the hospital, in his last conscious moment, before going into surgery, he gave his last message to Joe Hansen: “I am sure of the triumph of the Fourth International. Forward!”

Stalin, the bloody tyrant of the Kremlin, supreme leader of the counterrevolution, had finally managed to assassinate one of the most noteworthy revolutionaries which humanity has produced, who together with Lenin played a decisive role in the preparation, execution and triumph of the first socialist revolution on the planet.

The assassination of Trotsky was the culmination of the extermination of Lenin’s comrades in struggle, and of the great majority of the generation which made possible the victory of October. These were the methods that Stalin used to maintain his usurping and illegitimate bureaucratic regime.

Scarcely three months earlier, in the early morning of May 24, we had suffered a first, failed attempt on the life of Leon Trotsky in the big house in Coyoacán. On that occasion the painter Alfaro Siqueiros together with 20 or so Stalinist fanatics had stormed the house at Viena 19, preventing the comrade guards from leaving their quarters, raking it with intense fire while pouring machine-gun fire into the bedroom of my grandparents from three different directions, using Thompson sub-machine guns. Quick thinking by Natalia, who immediately pushed grandfather out of the bed and kept him in a corner of the dark bedroom, was what saved both of their lives. At the time I slept in the neighboring bedroom, and was grazed by a bullet on the big toe of my right foot.

Firebombs thrown into my bedroom, in order to burn the cabinets and destroy archives were the unmistakable calling card of Stalin, since only he could have been interested in their destruction.

It is difficult to describe on this occasion, how filled with joy and euphoria grandfather was at having emerged alive from this first failed attempt at assassination. Only the discovery of the absence of the guard on duty, Sheldon Hart, cast a shadow over the atmosphere.

But Lev Davidovitch knew that the break would be short and that his days were numbered. Every day when he got up he said, “Natasha, they have given us one more day of life.”

The question was, where would the next attempt come from? So much so that when he suffered the fatal attack, covered with blood, his glasses broken, standing in the door frame, when Natalia rushed up to him, he only exclaimed: “Jackson!” and pointed to the assassin who was pinned down by the guards, as if to say, “That’s where what we were expecting came from”!

My reuniting with grandfather was in Mexico, in August 1939, a year before his assassination. I was 13 years old at the time, and arrived from France with the Rosmers, old friends of my grandparents.

My memories of Lev Davidovitch during this last chapter, this last year of his existence, are very sharp and clear. It is difficult for me to describe with words, to impart the image of the living being, of the revolutionary with the magnitude and the brilliance of Leon Trotsky.

He was a human being of exceptional intelligence, and of total, absolute commitment to the struggle for socialism. His whole personality was shaped by the framework of this struggle. He was generous, supportive, patiently explaining and politically educating the comrades, with a great sense of humor, creating a jovial and warm atmosphere around him.

He was a tireless worker, not wasting a minute of his existence, radiating vitality and optimism. He had great admiration for human labor, where he did not permit privileges or distinctions. The word fear did not exist in his vocabulary.

What most impressed me about his person was his absolute certainty, his immovable confidence in the coming of socialism in the future of humanity.

A certainty that he acquired through his experiences of life, of having participated as a key personage and privileged observer in one of the most notable and astounding events in the history of humanity, the Russian Bolshevik Revolution, which in its beginning laid the basis for genuine socialism, and which later due to the adverse historical circumstances of the time degenerated under the blows of a counterrevolution. At least it demonstrated once and for all that socialism is a tangible and achievable reality.

Those of us who do not accept that there is eternal life, do believe that in the immortality of ideas.

Leon Trotsky had such an active and prolific mind in analyzing, elaborating theses and political slogans, that he transcribed and bequeathed to us an immense and inexhaustible arsenal of Marxist ideology and theory, the fruit of more than 40 years of revolutionary struggle, such that I venture to say that Leon Trotsky is still with us. His immense Marxist legacy enables us to analyze and understand all the past and present historical happenings, and to plan the future.

In the face of the increasingly voracious and brutal capitalist regime of today, in speaking of the socialist revolution, the words of Leon Trotsky come to mind: “Never was there a greater task on earth. The Party demands everything of us, totally and completely. In exchange, it gives us the immense satisfaction of participating in building a better future and carrying on our backs a particle of humanity’s greatest dream, and that our life will not have been lived in vain.”

Leon Trotsky’s last message to Joe Hansen was: “I am sure of the triumph of the Fourth International. Forward!”

This has not yet been accomplished. This is the duty and it is also the task to be carried out by the comrades who fight with the example and the ideas of the great revolutionary Leon Trotsky.

Let us remember his words:

“My faith in the socialist future of mankind is not less ardent, indeed it is firmer today, than it was in the days of my youth.

“Natasha has just come up to the window from the courtyard and opened it wider so that the air may enter more freely into my room. I can see the bright green strip of grass beneath the wall, and the clear blue sky above the wall, and sunlight everywhere. Life is beautiful. Let the future generations cleanse it of all evil, oppression and violence, and enjoy it to the full.”

Thank you.

Esteban Volkov

21 August 2009