November 2009

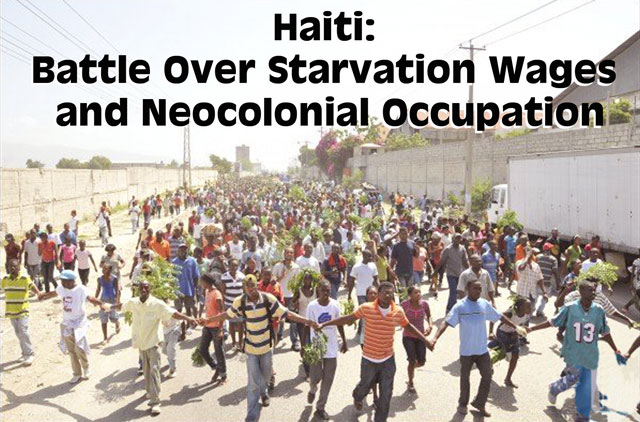

200 gourde ($5) daily minimum wage. Photo: François Louis/Le Nouvelliste

Haiti,

home of the first successful slave revolution in history, has for most

of

its independent history been condemned by the workings of the

capitalist system

to a threadbare existence of grinding poverty. Decades of economic

blockade of

the black Caribbean republic by the United States and the European

colonial

powers in the 19th century were followed by repeated occupations by

U.S. troops

and rule by U.S. puppet dictators in the 20th. Throughout, the

impoverished

country has been prevented from developing indigenous industry. Today

Haitian

agriculture has been ruined by the importation of subsidized rice from

Louisiana in the name of “free trade.” As the island nation reels under

the

“natural” disaster of annual hurricanes, any protest is put down by

“United

Nations” occupation forces acting as mercenaries for U.S. imperialism,

which

has its hands full in Iraq and Afghanistan.

For

years, the only images of Haiti have been of sheer desperation:

garbage-strewn

slums and rickety boats of fleeing refugees. But Haiti does have a

working

class, notably in garment factories in several “free trade zones,” and

in

August these workers fought an important battle against starvation

wages. In

May, both houses of the Haitian parliament voted to raise the legal

minimum

wage to 200 gourdes (roughly $5) a day, from the previous 70 gourdes

($1.75).

Even 200 gourdes is barely one-third of the daily minimum costs for

food,

shelter, clothing, transportation and education for a family of three,

and

below the U.N. definition of poverty ($2 per person per day). But

leading

businessmen declared that paying that miserable sum would drive them

into bankruptcy

and threatened to shut down half the factories in the country.

Demonstration for 200 gourde minimum wage

denounces repression byh MINUSTAH troops, August 2009.

(Photo: anarkismo.net)

Haitian

president René Préval took up the bosses’ lament,

demanding that legislators

repeal their earlier action. As the vote drew near, workers streamed

out of

plants in the industrial parks of the

capital, Port-au-Prince, to march on parliament. In a peaceful

demonstration of

hundreds on August 4, protesters complained: “70 gourdes won’t allow us

to live

decently. We can’t afford to eat on our wages. If we are sick, we can’t

go to

the hospital. We work from 6 a.m. to 7 p.m.” (AlterPresse, 4

August). After a parliamentary committee voted to

slash the 200 gourde minimum to 150, thousands of angry workers took to

the

streets August 5. On August 10, protests turned violent as workers and

students

responded to police tear gas by stoning official vehicles and the car

of the

U.S. chargé d’affairs, who sought refuge in a police station

besieged by

demonstrators. On August 11, after four walkouts in one week, the

bosses

decreed a lockout at the SONAPI industrial park, whose plants employ

14,000

workers.

Finally,

on August 18, the pliant deputies and senators saluted their capitalist

masters

and slashed the legal minimum to 125 gourdes (a little over $3) a day.

It was a

bitter defeat for the workers in the first organized class mobilization

under

the U.N. occupation. In 2008, as the cost of rice and other staples

rose by 50

percent, hunger riots that began in the provinces and spread to the

capital

were put down by the MINUSTAH (United Nations Stabilization Mission in

Haiti)

military and police forces with a toll of several dead. But those were

largely

spontaneous acts of despair by impoverished slum dwellers. In the

recent

marches workers used their strength to shut down production. Though the

outcome

was a setback, it was a battle that could lead to more powerful and

conscious

working-class struggle in the future. The key is revolutionary

leadership.

Many

workers drew lessons about the country’s rulers. One remarked: “It’s

sad to see

that the president of the republic chooses to defend the interests of

the

bourgeoisie rather than ours.” Some showed an awareness of their own

power,

dismissing the bosses’ threats: “They need us.... If they say their

factories

will close their doors it’s false.” Demonstrators trampled on the flags

of the

different countries whose troops make up the MINUSTAH, saying “These

are the

flags of occupation.” This was also the first time under the occupation

that

workers have been joined by students, who since the beginning of the

year have

occupied the National Teachers College and different faculties

(ethnology, law

and medicine) of Haiti’s State University (UEH). This shows the

potential for a broader

class struggle against the imperialist occupation and sweatshop

exploitation.

Militants

seeking to cohere a revolutionary nucleus to lead the struggle for a

workers

party in Haiti would intervene to deepen the alliance of students and

workers,

together with poor peasants and slum dwellers who have traditionally

provided

the bulk of anti-government protests in the poorest country in the

hemisphere.

Although employed industrial workers are a distinct minority, their

leadership

is vital because of their economic power and class position. In forging

a

revolutionary consciousness, it is vital to combat illusions in

petty-bourgeois

and bourgeois nationalist forces. Préval was elected with the

votes of poor

people who saw him as a stand-in for former president and populist

priest Jean-Bertrand

Aristide and his Lavalas (“avalanche”) political movement. Yet both Aristide and

his former protégé been loyal enforcers for the

Haitian bourgeoisie and the imperialist overlords.

Former U.S. president Bill Clinton, now

U.N. special envoy to Haiti, glad-handing with imperialist investors at

World Bank conference in Port-au-Prince, October 2009. (Photo: Ramón Espinosa/AP)

Former U.S. president Bill Clinton, now

U.N. special envoy to Haiti, glad-handing with imperialist investors at

World Bank conference in Port-au-Prince, October 2009. (Photo: Ramón Espinosa/AP)

Today,

U.S. rulers continue to dominate the politics of Haiti and the

neighboring

Dominican Republic. Many Haitians and Haitian émigrés in

the U.S. and Canada

saw the election of Barack Obama, the first black president of the

United

States, as a promise of a brighter future. Earlier this year, United

Nations

secretary general Ban Ki Moon appointed former U.S. president Bill

Clinton as

special U.N. envoy to Haiti. Clinton, as the new colonial gouverneur,

would oversee efforts to make Haiti safe for foreign

investors. To this end he “gave his stamp of approval” to a World Bank

conference in Port-au-Prince that attracted several hundred investors

who “showed

up to network and discuss possible projects” (New York Times,

5 October), although so far without results. Simultaneously,

former U.S. president Jimmy Carter was in Santo Domingo, trying to coax

Dominican leaders into easing up on Haitian immigrants. Meanwhile,

Washington

continues to lord it over both countries, economically and militarily.

The

struggle for the liberation of the first black republic, whose working

masses

today toil in conditions of near slavery, must be international in

scope. The

fight against the “U.N.” occupation must also be waged in countries

such as

Brazil, Canada and Chile that supply mercenary troops and cops to do

the dirty

work for Yankee imperialism. Dominican workers should come to the

defense of

their Haitian class sisters and brothers, some of whom work for the

same

bosses, in common class struggle. This includes defending the rights of

the

roughly one million residents of Haitian origin in the Dominican

Republic who

are denied citizenship and persecuted by the racist rulers who create

the

climate for lynch mob terror. Above all, workers in the U.S. must

undertake

solidarity action, for the free trade zone factories are owned by or

produce

for major U.S. companies, and it is Washington that ordered the U.N.

occupation.

Neocolonial

Occupation Troops Enforce Starvation Wages

The

battle over Haiti’s minimum wage has been brewing for a long time. In

reality,

even if it were raised to 200 gourdes, it would be less in real terms

than it

was 20 years ago (adjusted for inflation). Everyone

agrees that it is impossible to live on such a wage, including

President

Préval, who asked in a June 17 letter to legislators: “Would 200

gourdes let

you live as one should? I say no, if you take into account the price of

transportation, housing, school, and so on.” The issue became heated

with the

passage of the HOPE (Haitian Hemispheric Opportunity through

Partnership

Encouragement) Act by the U.S. Congress in December 2006 and the HOPE

II Act

two years later. This trade preference provides for duty-free import to

the

United States of apparel assembled in Haiti from cheap Asian yarns,

fabrics and

components. But there is a price advantage only if wages in Haiti’s

factories

stay below Asia’s lowest-wage country, Bangladesh.

Last

December, Steven Benoit, a parliamentary deputy from the middle-class

suburb

Pétion-Ville and former member of President Préval’s

Lespwa (Hope) party, took

up the issue of the 200 gourde minimum wage. After much travail he

managed to

push the law through the Senate and Chamber of Deputies, with unanimous

or

near-unanimous votes in both houses of the legislature. When business

leaders

loudly objected that they would go bankrupt, Benoit asked to see their

tax

returns. Lo and behold, the companies had filed phony reports claiming

to be

losing money five years in a row even as they were investing to expand

production. How many jobs had been created with the present low minimum

wage,

he asked, to no avail. TV spots opposing the higher wage suddenly

appeared from

unknown and well-financed “associations of the unemployed.” A

“Dominican

industrialist” declared on television he couldn’t afford to pay Haitian

workers

$5 a day even as the Dominican government passed a law for a $9 daily

minimum

wage.

With

the hypocrisy of the capitalists and the Préval government

exposed, the issue

of the minimum wage galvanized opposition in all sectors of Haitian

society.

Since early 2009, students in several faculties of Haiti’s State

University

have been mobilized to protest the neglect of public higher education

under the “neo-liberal” policies implemented by the government and the

policies

of university authorities, as well as supporting the demand for a

minimum wage

of 200 gourdes. After the occupation of the offices of the school of

education

in late February/early March, students at the faculties of ethnology,

law and human

sciences joined the struggle. Most recently, students in the school of

medicine

and pharmacology have repeatedly occupied their faculty, and been

expelled by

mobilizations of various elite police units – CIMO, SWAT and BIM – with

dozens

of arrests. A coalition of peasant groups, 4 G Kontre, and peasants in

the

Artibonite region also supported the demand for 200 gourdes.

On May 1, workers in Batay Ouvriye (Workers Struggle), public sector workers (CTSP), peasants in the Tèt Kole Ti Peyizan (small peasants association), and women’s groups demonstrating for the minimal demand of a 200 gourde minimum wage were repressed by the CIMO riot police. As protests heated up, the “blue helmet” U.N. “peacekeepers” have come to the rescue of the Préval government as it enforces starvation wages. On June 18, during a funeral march for Father Gérard Jean Juste, a popular priest of the Tit Leglize (“little church”) liberation theology movement, Brazilian MINUSTAH troops opened fire on the crowd of Lavalas supporters, killing a young man from the Delmas slum, Kenel Pascal. The spokeswoman for the U.N. mission in Haiti justified repression against the march by denouncing UEH student protesters as casseurs (window smashers) who must not be allowed to “attack private property” (AlterPresse, 18 June). In mid-July, U.N. troops used tear gas against a student demonstration.

Mass arrests by Brazilian MINUSTAH troops, Village de Dieu, Port-au-Prince, February 2008. Military

police use same “counterinsurgency” tactics in poor areas of Rio de Janeiro. Brazilian Trotskyists

demand: drive Brazilian troops out of Haiti and out of the favelas! (Photo: Jean Ristil/HaitiAction.net)

Then

on August 5, MINUSTAH troops killed another young man, Ricardo Morette,

and

wounded a dozen as the “blue helmets” took down barricades of

demonstrators

protesting the lack of electricity in the town of Lascahobas. Until

recently

these mercenary troops for U.S. imperialism had concentrated on

“pacifying” the

400,000 residents of the slums of the capital, Port-au-Prince. This led

to a

series of massacres in Cité Soleil, Bel Air and other

impoverished areas in

2005 and 2006. As our comrades of the Liga Quarta-Internacionalista do

Brasil

(LQB) have pointed out, Brazilian troops are using the same

“counter-insurgency”

tactics in Haiti that are employed by military police against residents

of the favelas (slums) of Rio de Janeiro. This

is confirmed by Brazilian journalist Pedro Dantas who reported, “Army

sources confirmed

that techniques employed in the occupation of the Morro da

Providência favela are the ones Brazilian

soldiers

use in the United Nations peacekeeping mission in Haiti” (O

Estado de S. Paulo, 15 December 2007).

Some

Brazilian leftist groups have politely urged the Brazilian government

to

withdraw from Haiti, while expressing “full understanding” for the

troops faced

with the “difficulties” of their mission and dismissing Haitians

resisting the

MINUSTAH as “organized gangs linked to drug trafficking” (Causa

Operária, 22 October 2004). In contrast, the LQB and its

trade-union supporters in the Comitê de Luta Classista denounced

Brazilian

president Lula as Washington’s “sheriff” in Latin America and called on

Brazilian workers to “aid the Haitian working people in expelling the

invading

Brazilian troops.” A motion introduced by the CLC with this call was

passed by

the Rio teachers union, SEPE, and by the national teachers union, CNTE

(see

“Drive Brazilian Troops Out of Haiti!” The

Internationalist No. 20, January-February 2005). Five years after

the U.N.

forces began patrolling Haiti, now that Haitian workers and students as

well as

slum dwellers have confronted the MINUSTAH forces over the minimum

wage, it is

high time for a class mobilization to

throw out these mercenary enforcers of

starvation wages.

Lynching

and Persecution of Haitians in the Dominican Republic

While

Haitians are rounded up and shot down by imperialist henchmen “at

home,” next

door in the Dominican Republic right-wing forces have been whipping up

racist

hysteria the roughly one million residents of Haitian origin, the bulk

of whom

have been living and working there for most or all of their lives. In

2005, there

was a wave of pogroms (ethnic massacres) and the mass expulsion of tens

of

thousands of Haitians and dark-skinned Dominicans (see “Stop

Persecution of

Haitian Workers in the Dominican Republic!” The

Internationalist No. 23, April-May 2006). Since that time, the

Internationalist Group has regularly participated in monthly pickets of

the

Dominican consulate in New York City called by Grassroots Haiti. The IG

also

helped initiate an emergency demonstration in August 2008 by Dominican,

Haitian

and U.S. activists demanding an end to the deportations and racist

violence

against Haitians and opposition to the Dominican nationality law which

denies

citizenship to children of Haitian origin born in the D.R. (see The Internationalist No. 28, March-April

2009).

Now

the anti-Haitian hysteria and racial/ethnic attacks are escalating

again. The

GARR (Groupe d’Appui aux Rapatriés et Refugiés – Refugee

Support Group) has

reported a series of murders and expulsions since the start of the

year: in

January, three Haitians killed by Dominican police and several Haitians

killed

by machetes near the border; in February, 3,000 Haitian immigrants

forced out

of their homes in Santiago province and more than a hundred forced to

flee for

their lives in Higüey, as well as three more Haitians killed by

the Dominican

police; in March, a Haitian pastor and a Haitian professor at the UASD

(Autonomous University of Santo Domingo) murdered; in April, 40

Haitians

brutalized by police on a bus as they were being deported. And on May

2, Carlos

Nérilus, was decapitated with an axe in broad daylight on a

street in Santo

Domingo while a crowd applauded. Local leaders then announced they were

going

to drive all Haitians out of the neighborhood. This horrendous

execution led to

demonstrations in Haiti, and even the prime minister, Michelle

Pierre-Louis

issued a mild plea, but Haitian president Préval refused to

protest, saying it

was up to the Dominican authorities.

The

spectre of a repetition of the 1937 massacre of tens of thousands of

Haitians

in the Dominican Republic is ever-present. That slaughter by the

dictator

Rafael Trujillo was carried out with the complicity of the Haitian

government,

which profited from supplying thousands of workers for back-breaking

labor

during the zafra (harvest) on

Dominican sugar plantations, and of the United States, which set up

this system

of virtual slave labor during the 1920s when it militarily occupied

both

countries on the Caribbean island of Quisqueya (Hispaniola). Today, as

well,

Dominican sugar production depends on Haitian laborers, some imported

with the

aid of officials and governments on both sides of the border, and many

who have

lived year-round in the miserable bateyes

(slums) on the edge of the plantations. Construction projects in Santo

Domingo

also depend heavily on Haitian labor. Yet the rulers assiduously stoke

racial/ethnic hatreds even as Haitian elites spend their vacations in

the

Dominican Republic, send their children to university in Santo Domingo

and

invest their profits in the D.R.

And

despite the international publicity to the grisly decapitation of

Carlos

Nérilus, the lynchings continue. The most recent case was the

murder of three

Haitians who were shot to death, dismembered and their bodies burned in

ovens

used to produce charcoal near the Dominican border town of

Jimaní. The victims

were part of a logging operation supplying wood to this illegal trade.

While

environmentalists blame deforestation on desperately poor Haitian

peasants, in

fact it is the result of an industry run by Dominican-Haitian cartels

as

extensive as the drug trafficking mafia in this region, according to an

investigative report in the Santo Domingo daily Listín

Diario (25 October). And whether the crime was committed by

Dominican park rangers who profit from the trade, by the murderous

military

border patrol CESFRONT, or by farmers who have organized manhunts to

track down

Haitians, the ruling classes of both countries reap the superprofits

from this

deadly enterprise.

While

many of the killings have been carried out by lynch mobs of poor and

often

dark-skinned Dominicans, the racist capitalists exploit Dominican

workers as

well. Grupo M runs several garment factories with low-wage Haitian

workers in

the CODEVI free trade zone at Ouanaminthe just across the river from

the

Dominican town of Dajabón. The border there is now guarded by

the MINUSTAH,

which built a metal gate to regulate traffic. The same factory owner

has

plants in the Dominican Republic which supply the textiles and do

finishing

work on clothing produced in Haiti for chains including Old Navy, Ralph

Lauren,

Donna Karan, VF Corporation, Banana Republic, American Eagle and

Wal-Mart. Other

major corporations are the American jeans maker Levi-Strauss, with

1,600 workers

in two plants in the CODEVI industrial park, and Hanes underwear, which

produces its entire line of T-shirts there. Meanwhile, the products of

these

plants are exported to the U.S. under the CAFTA (Central

American-Dominican

Free Trade Agreement), while other Haitian plants using textiles

imported from

Asia are covered by the HOPE Act.

But

even though Dominican and Haitian workers are exploited by some of the

same

bosses, and despite the fact that they are both oppressed by Yankee

imperialism

(which sends U.S. soldiers to train the CESFRONT border troops and

hires

MINUSTAH mercenaries to patrol the Haitian side of the border), and

although

Dominican labor and left groups stage nationwide strikes and work

stoppages

annually if not more often, united action by Dominican and Haitian

workers against

their common exploiters and oppressors is almost non-existent. Why?

Worker at factory of Dominican Grupo M

producing Levi jeans in CODEVI free trade zone in Ouanaminthe, November

2007. (Photo: No Sweat)

Worker at factory of Dominican Grupo M

producing Levi jeans in CODEVI free trade zone in Ouanaminthe, November

2007. (Photo: No Sweat)

One

reason is the dominance of bourgeois and petty-bourgeois nationalist

politics, as opposed to proletarian internationalism,

among leftists on both sides of the border. This is a legacy of

Stalinism,

which replaced the Leninist program of international socialist

revolution with

nationalist “popular fronts” seeking (capitalist) “democracy.” Another

key

factor is the huge difference in living standards. According to a

Congressional

Research Service report on “The Haitian Economy and the HOPE Act”

(October

2008), wage levels in Haitian factories “average as little as one-third

of

those in the Dominican Republic,” while the gross domestic product per

capita

of the D.R. is ten times that of Haiti – roughly the difference between

the

United States and Mexico. Income and wage differences of that magnitude

are

difficult to overcome on the basis of simple trade-unionism, focusing

on the

struggle over the price of labor power.

Unity

of Haitian and Dominican workers will not be brought about through

reformist labor

struggles within the framework of capitalism, but only on the basis of

a

broader class struggle against the

imperialist system. The whole history of Haiti over the last century

underscores

Leon Trotsky’s perspective of permanent revolution: in the imperialist

epoch,

even the democratic tasks of the

bourgeois revolutions cannot be achieved short of the taking of power

by the

working class, supported by the peasantry, which proceeds to

expropriate the

capitalists and extend the revolution internationally. In a country

with a

numerically weak proletariat such as Haiti, throwing off the

imperialist yoke can

only come about as part of a struggle spanning borders from the island

of

Quisqueya to Brazil to the United States. And that requires above all

building revolutionary workers parties as part of

struggle to reforge the Trotskyist Fourth International as the world

party of

socialist revolution.

With

a million Dominican and Haitian immigrants

concentrated in New York City, this center of world finance capital

will be the

crucible for cohering the nucleus of such parties based on proletarian

internationalism. Just as youth from India, Pakistan and Bangladesh

have

founded common organizations here in the face of the deadly nationalism

that

has wracked their homelands, working people from the divided Caribbean

island can

make common cause in the face of the imperialist would-be masters of

the

universe who would enslave them all. As a start, the Internationalist

Group and

League for the Fourth International seek to unite Haitian and Dominican

immigrants in fighting to expel the

MINUSTAH occupation troops and police from Haiti and kick

U.S. military “advisors” out of the Dominican Republic, and to

demand full citizenship rights for

Haitians in the D.R. and for all immigrants in the U.S. ■

To contact the Internationalist Group and the League for the Fourth International, send e-mail to: internationalistgroup@msn.com