December 2006

War and Anti-Labor Attacks

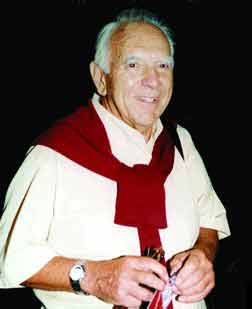

Italian war minister Arturo Parisi (left) and prime minister Romano Prodi (right) send off "peace-

keeping" force to Lebanon to act as border guards for Israel. (Photo: Pier Paolo Cito/AP)

Ever

since the “Unione” – Italy’s governing coalition of assorted

ex-Christian

Democrats, ex-Stalinists and Greens – came into office last April, it

has

relentlessly pursued two goals: slashing labor costs at home to make

Italian

industry “competitive” and militarily occupying foreign countries

according to

the dictates of U.S. imperialism (and its Israeli allies). From the

standpoint

of the Italian working class and the oppressed masses of Africa and the

Middle

East, not a euro cent’s worth of difference separates the former

“center-right”

government of Silvio Berlusconi from the “center-left” government of

current

prime minister Romano Prodi. The Italian capitalists, on the other

hand, are

for the moment banking on Prodi’s popular front – which includes, in

particular, Rifondazione Comunista (PRC, Party of Communist

Refounding), whose

leader, Fausto Bertinotti, now shamelessly presides over the Chamber of

Deputies of Italian imperialism. Sometimes referred to as “far left” in

the

bourgeois press, the PRC’s policies are

utterly

reformist, often to the right of the pro-capitalist policies of the

Italian

Communist Party of the past.

Bertinotti’s

capitalist masters are hoping that he and Prodi will take up where

Berlusconi

left off, dismantling labor protections and conducting imperialist

military

adventures. Prodi knows his assignment: during the election campaign,

in his

nationally televised debate with Berlusconi, Prodi intoned, “We have to

lower

labor costs. We have to give a push to the system.” Now the Prodi

government

has rammed through an austerity budget with multi-billion euro cuts in

health,

local government and education, while resuming the dismantling of the

public

pension system begun in 1995. In addition to raising the age of

retirement,

according to a “memorandum of understanding” between the government,

unions and

industrialists, beginning next year workers’ severance pay (TFR) will

be

funneled into privatized pension funds that will “invest” in the stock

markets

while minimum state pensions are cut to the bone. All this is done with

the

support of the union bureaucracies, which are setting up their own

pension funds

to get in on the speculative feast. And now the government is preparing

the

privatization of the state airline, Alitalia. The PRC, having

supported the first Prodi government (1996-98) which privatized Telecom

Italia,

slashed job protections and set up concentration camps (CPTs) for

undocumented

immigrants, is also backing this attack on workers’ livelihoods.

Banner calling for “generalized strike” in workers demonstration “against the budget of war and job

instability.” Air and ground transport workers walked out as 1.5 million struck. (Photo: Luca Bruno/AP)

But

the assault has not gone without protest. On November 4, 150,000

demonstrated

in Rome to demand an end to precarietà (temporary jobs).

On November 17,

some 1.5 million workers struck against the financial law, with over

300,000

demonstrating in the streets. Among the protesters were many students,

while

the striking workers were mainly from the various syndicalist

rank-and-file

committees (Cobas, SLAI Cobas, CUB) and the left wing of the CGIL

(Italian

General Labor Federation, led by the PRC). Then on December 7, the top

union

bureaucrats visited the largest factory in Italy, Fiat’s Mirafiori

plant in

Torino, for the first time in 37 years, to sell the budget. The workers

weren’t

buying. “Bertinotti betrayed us,” shouted one worker to general

applause. “We

shouldn’t be a rubber stamp for the government” said another to Luigi

Angeletti

of the social-democratic UIL union federation, reminding him that

“these

governments are no friends” of the workers. Raffaele Bonanni, head of

the

formerly Christian Democratic federation, CISL, was booed as were

others of the

bureaucrats. Workers bombarded CGIL leader Giuglielmo Epifani for two

hours with

complaints about the threats to pensions. But in the end, despite the

workers’

boos at Mirafiori, the budget sailed through parliament without a hitch.

Immigrants

and immigrant workers have been a particular target of attack. The

latest case

was a

racist assault on a camp of Rom (“gypsies”) on December 21. The week

before, they had

been evicted from a camp in Milano. They were supposed to be

temporarily lodged in a tent city in nearby Opera, but when buses with

75 Roms

arrived, a racist mob had drenched the tents with gasoline and burned

them.

Half of those thrown out into the December cold were children,

including a number of newborn babies.

The attack was spearheaded by fascists, both skinhead squadristi (attack squads) and

supporters of the

fascist party Aleanza Nazionale, along with the virulent anti-immigrant

racists

of the Lega Nord (Northern League). The assault was also “tolerated, if

not

openly supported, by many citizens who voted for the center-left” (Il

Manifesto, 30 December). Local authorities responded by holding a

“dialogue” with the vigilantes. The camp has since been reestablished

with a

police presence, but the racists are still there menacing it and the

mayor (member of the Left Democrats) says they can only stay until

March. The situation

cries out for a massive workers mobilization to sweep away the fascist

scum and teach them a lesson with proletarian power.

But the reformist misleaders haven’t lifted a finger to defend the Rom.

On

the military plane as well, the Italian popular front has gone out of

its way

to maintain continuity with Berlusconi. After nine months in office, it

finally

withdrew the Italian contingent from Iraq, while reconfirming its

commitment

to, and even increasing the budget for, Italian troops in the NATO

occupation

of Afghanistan. On top of this, the Unione is now providing border

guards for

Israel. On August 29, Prodi stood pompously on the deck of the navy’s

flagship,

the light aircraft carrier Giuseppe Garibaldi, and blessed his

troops

departing for Lebanon. The Garibaldi (what a misuse of that

great

revolutionary’s name!) steamed from Brindisi at the head of a flotilla

carrying

2,500 soldiers in addition to naval personnel. They make up the largest

component of the multinational “peacekeeping” force summoned by

Washington and

Tel Aviv in the wake of the U.S.-backed Israeli invasion of Lebanon.

While the

Zionist militarists laid waste to much of the country, using U.S.-made

cluster

bombs against the civilian population, the Hezbollah militia fought the

Israeli

army to a standstill in southern Lebanon.

Having

failed to do so by military means, Bush and the Israeli rulers turned

to the

United Nations to seek to disarm Hezbollah through diplomacy and an

occupation

army of the European imperialists. While the right-wing opposition

makes a show

of criticizing this military adventure, even the “communist” Bertinotti

declares himself “happy” that Italy “has returned as a force for peace

in the Mediterranean

area” (AGI, 26 August)! Recently, foreign minister Massimo D’Alema of

the Left

Democrats (DS) visited the troops in Lebanon warning of possible

attacks on

this phony “peace force” by Al Qaeda. Meanwhile, Israel crows that the

Italians

are doing its bidding (“Italy: World Won’t Tolerate Syrian Arms

Shipments to

Hezbollah,” Haaretz, 1 September). In January, Italian general

Gerometta

will assume command of the entire 15,000-strong UNIFIL force. For now,

the

“Italian Joint Task Force” is concentrating on building good relations

with the

predominantly Shiite Muslim local population. But that will change as

soon as

they try to enforce UN Security Council resolution 1701 calling for

disarming

Hezbollah.

Parliament

must vote to renew authorization for the Afghan expeditionary force

this month,

putting left-wingers in the PRC in a quandary. Last summer most of them

voted

“yes” to the Afghan war while claiming to oppose it. Not so long ago,

in 2003,

millions demonstrated in Italy against the U.S. invasion of Iraq, but

today

only a few thousand participate in protests demanding Italian troops

get out of

Afghanistan and Lebanon. The bulk of the Italian left may make tepid

criticisms

of Prodi’s foreign policy and oppose the “cowboy” antics of George Bush

and the

U.S. imperialists in the Near East. But rather than fighting for

socialist

revolution, most of the “antiwar” forces yearn for a “peace-loving” Italian

imperialism. Revolutionary internationalists call instead to drive all

the

imperialists out of the Near East, and for proletarian mobilization to

defeat

imperialist war.

From

Mussolini to Berlusconi

Media mogul Silvio Berlusconi when he was

prime minister. Il cavaliere openly

sports his bonapartist

ambitions, bragging that he is “greater than Bonaparte.” (Photo:

Gregorio Borgia/AP)

Berlusconi’s

regime was the continuator of the right wing of the Christian Democracy

(DC),

the dominant bourgeois party of postwar Italy, created with CIA and

Vatican

money and populated with ex-fascists and mafiosi. The mission

of the DC

was to salvage Italian capitalism from the wreckage of Mussolini’s

fascism, at

a time when the discredited and disorganized bourgeoisie faced an

increasingly

militant proletariat, a significant section of which had kept its arms

from the

partisan struggle against the Nazis. Under the leadership of Palmiro

Togliatti

and the Italian Communist Party (PCI), loyal to Stalin’s alliance with

“democratic” imperialism, the DC was allowed to reconstitute the

capitalist

order. An excruciatingly accurate depiction of this scene closes

Bernardo

Bertolucci’s film, 1900, when at a workers tribunal at the end

of World

War II the boss is told, “il boss non esiste più” – the

boss is no more

– until the official PCI representatives arrive, disarm the people and

permit

the boss to proclaim, “si, il boss ancora esiste” (yes, the boss

still

exists).

For

the next thirty years, through the working-class explosions in the

1960s and

’70s, the PCI tops (and their supporters in the CGIL unions) functioned

as

loyal “labor lieutenants of capital.” This culminated in the PCI’s

“historic

compromise” of the mid-’70s, when the PCI deputies gave essential

parliamentary

support to DC government of Giulio Andreotti (and fingered factory

workers as

Red Brigade members to the police). Try as they might, however, the

Stalinist

misleaders could not save Andreotti and his mafia- and fascist-ridden

party,

which finally broke apart in the early 1990s under the weight of a

series of

corruption scandals that had begun a decade earlier. The PCI/CGIL tops

tried to

prove their reliability to the capitalists by sacrificing the scala

mobile

(the cost-of-living escalator that adjusted wages for inflation), in a

July

1992 accord with the employers and government, and gutting other

workers’

conquests won in the autunno caldo (hot autumn) of 1969. But

instead of

putting a popular front in power, this demoralized the workers and

brought in

the first Berlusconi government of 1994-96.

The

“center-right” Berlusconi I government fell amid internal squabbling

and

working-class discontent. New elections led to a “center-left”

government under

former Christian Democrat Romano Prodi, who lasted a bare two years (1996-98), to be replaced by another

popular-front cabinet led by former Stalinist D’Alema of the DS, whose

government escalated attacks on the workers. This, in turn, led to the

electoral victory in 2001 of the Berlusconi II government, which

remained in

power for the full five-year period. In national elections last April

10-11,

the alternate leadership of the Italian ruling class, the Unione

coalition, won

by a razor-thin margin and installed the Prodi II government. The

narrow

outcome – barely 25,000 votes separated the two blocs in the Chamber of

Deputies, out of a total of about 38 million cast – was largely due to

the

Unione’s insistently anti-working class program, which promised to make

life

worse for workers than under Berlusconi. But the cyclical alternation

of right

and “left,” between Berlusconi and Prodi, masks the underlying drive by

the

entire bourgeoisie to dismantle the remains of the postwar “social

state” and

boost Italian “competitiveness” by undoing labor gains.

Working-class

opposition to the right-wing regime had been massive since Berlusconi

took

office in 2001 with an agenda of privatizations, attacks on union

protections,

pensions and civil liberties (disguised as a U.S.-style campaign

against

“terrorism”), as well as a racist offensive against immigrants.

Berlusconi

dispatched 1,300 troops to Afghanistan and 3,000 to Iraq in support of

U.S.

imperialism and its wars, to the outrage of the whole of the Italian

working

class, most students and a large part of the petty bourgeoisie. As a

result,

Italy became a huge stage for demonstrations of protest and resistance.

A

series of combative industrial and service worker strikes culminated in

a 10

million-strong general strike in October 2003, and the two largest

demonstrations in postwar Italian history, both of which took place in

Rome. In

2002, 2 million demonstrated against the government’s economic

policies, and

the following year 3 million marched against Italy’s participation in

the U.S.

imperialist onslaught in Afghanistan and Iraq.

In

the face of such widespread opposition, the Italian bourgeoisie failed

to bring

the workers to heel. For five years it backed Berlusconi’s coalition,

which in

the main consists of four parties. Forza Italia (a soccer

slogan,

meaning “Go Italy”), the largest of the four, received 24 percent of

the vote

in 2006; it was created with Berlusconi money and Vatican support to

rally

demoralized elements of the defunct mafia-ridden Christian Democracy.

The Alleanza

Nazionale (National Alliance), the second party in Berlusconi’s

coalition

(receiving over 12 percent of the 2006 vote) is the new name of the

Italian

fascists. It was changed from Mussolini’s “Movimento Soziale Italiano”

in 1995,

as part of the fascists’ efforts to sanitize their image (including

kicking out

the dictator’s granddaughter and dressing up their leader, Gianfranco

Fini,

Berlusconi’s foreign minister, in a business suit instead of a black

shirt).

The third component is the UDC/DC, remnants of the old

Christian

Democratic Party (7 percent), and the fourth is the racist

anti-immigrant Lega Nord

(Northern

League, 4.5 percent), led by

Umberto

Bossi, a bribe-taker given to screaming vulgarities and threats of

violence

against other politicians.

Despite

the new names, the center-right “Pole of Liberty” coalition thus brings

together all the usual suspects of post-war Italian capitalism: the

super-rich,

Vatican operatives, corrupt politicians, big-time criminals, fascists

and

racist thugs. But it is an uneasy alliance. The founding principles of

Lega

Nord, for example, were hatred of Italian national unity and love for

“Padania,” a mythical Nordic-style land to be formed by the secession

of

northern Italy from the Mezzogiorno (the poor southern regions of

Italy). Bossi

brought down the coalition once before, in 1994, ending Berlusconi’s

first,

short-lived reign. Greed for money and power, and hatred of the working

class,

however, brought Bossi back in the fold, and he became Minister of

Reforms in

the second cabinet.

For

five years the strategy consisted of crude frontal assaults against the

hard-won gains of the Italian working class, which, damaging as they

were,

ultimately proved insufficient to break worker militancy. Berlusconi’s

last-ditch effort was an attempt to grab more power through forcing

changes in

the 1948 Italian constitution. When he lost in parliament, he called a

national

referendum. Bossi loudly proclaimed that he would move to Switzerland

if it

didn’t pass. Its decisive failure in late June (61 percent voted “no”)

was in

part due to heavy resistance in the South, where sensitivity to any

scheme

involving Bossi runs high. In response to the defeat of the referendum,

Marco

Formentini, Lega Nord representative in the Europarliament, sneered, “Italia

fa schifo, gli Italiani fanno schifo” (Italy stinks, the Italians

stink).

The workers will remember these names and reckon with them

appropriately, as

the partisans did with many at the close of World War II. But the

1943-45

workers uprising against Mussolini and the retreating German

imperialists was

sold out and proletarian revolution blocked by the Stalinist PCI and

social

democrats through a popular front with right-wing Catholic politicians.

Berlusconi’s

Bonapartist aspirations and megalomania (Il cavaliere has

described

himself as “greater than Bonaparte” and the “Jesus Christ of

politics”), as

well as his brazen use of political power to advance his private

commercial

interests, may have put off some bourgeois backers, but the decisive

factor for

them was his failure to gain the deep cuts in labor costs they

demanded. As

Maurizio Beretta, chief of Confindustria, Italy’s powerful syndicate of

capitalists, portentiously remarked, “the problem of pensions is a

rather

delicate one” (AGI, 11 September). So in the face of tenacious

working-class

resistance to Berlusconi, the capitalists seek to serve their purposes

with the

less blunt instrument of the Unione. And who better to understand the

bourgeoisie’s concerns than Prodi, himself Confindustria’s chief during

the

1980s and again in 1993-94?

From

Berlusconi I to Prodi II: Imperialist War and Anti-Worker Attacks

L’Unione

is a classic “popular front” that binds the workers to their class

enemy by

means of an alliance between sections of the ruling class and the mass

organizations of the working class (parties and unions). Its program is

capitalist austerity “at home” and imperialist militarism abroad.

Berlusconi’s

fascist-ridden wing of the bourgeoisie has been temporarily sidelined

by this

election, but his replacements are eager for the chance to discipline

the

workers.

The

largest bourgeois component of the Unione is the Margherita (Daisy),

the

reconstituted liberal wing of the old Christian Democratic Party (a/k/a

the

Aldo Moro wing). Margherita is closely allied with the Left Democrats

(DS), one of the two largest splinters from the defunct Italian

Communist

Party.

The “Ulivo” (Olive Tree) lash-up of ex-Christian Democrats and

ex-Stalinists

resembles the “historic compromise” – the desperate attempts in the

late 1970s

by the PCI under Enrico Berlinguer to formally subordinate itself to

Giulio

Andreotti’s Christian Democrats. This came to an abrupt end in 1978

with the

kidnapping and murder of Moro, the main Christian Democratic proponent

of an

alliance with the PCI). The ex-Stalinists of the DS, however, have

moved much

further down the road of class collaboration, and today the Ulivo bloc

constitutes the bourgeois core of Prodi’s government, with over 30

percent of

the popular vote and 220 seats (out of 630) in the Chamber of

Deputies. Prodi

appointed old-line Stalinist bureaucrat Giorgio Napolitano as President

of the

Republic.

Rifondazione Comunista

leader Fausto Bertinotti (left) and Democratic Left leader Massimo

D'Alema during April 2002 general strike against plan by right-wing

Berlusconi government to make it easier to fire workers. Now Bertinotti

and D'Alema are part of popular-front government that is pushing to

"flexibilize" job security. (Photo:

Giorgio Borgia/AP)

Rifondazione Comunista

leader Fausto Bertinotti (left) and Democratic Left leader Massimo

D'Alema during April 2002 general strike against plan by right-wing

Berlusconi government to make it easier to fire workers. Now Bertinotti

and D'Alema are part of popular-front government that is pushing to

"flexibilize" job security. (Photo:

Giorgio Borgia/AP)

Because

of its open hostility to the working class, however, the Ulivo could

not hope

to form a government by itself. Many workers remembered how in 1998-99

when

D’Alema was prime minister his government pushed through anti-strike

laws and

tried, unsuccessfully, to gut the pension system. The Ulivo’s plan to

continue

and even quicken the pace of the Berlusconi-initiated attacks on

pensions and

welfare spending requires that it have more credible allies to the left

– those

with closer ties to the working class and Italy’s large and

heterogeneous

milieu of contestazione (active opposition). Among these allies

are the Greens (who got 2.3

percent of the vote in April); Rosa

nel Pugno

(Rose in

the Fist, 2.6 percent), the new name of the old Radical Party, now

fused with a

splinter from Bettino Craxi’s corrupt Socialist Party; and the more

traditional

Stalinists of the Party of Italian

Communists (PdCI, 2.3 percent). But

the linchpin

of the popular front is the Partito

di Rifondazione Comunista led by

former

CGIL militant Fausto Bertinotti, who is now Prodi’s Speaker of the

Chamber of

Deputies.

The

PRC received 2.2 million votes (5.8 percent) in the Chamber and 41

deputies,

and 2.5 million in the Senate (7.4 percent) and 27 senators.

Rifondazione’s

vote totals are up by well over half a million over 2001, and represent

the

hopes of the most class-conscious Italian workers. Unfortunately, these

hopes

are misplaced. The PRC leadership, no less than that of any of its

Unione bloc

partners, is deeply committed to preserving the rule of the Italian

capitalists. To prove this to all the world, Prodi with Bertinotti’s

support,

called for a series of early votes to renew the Italian commitment to

the

imperialist war in Afghanistan. Bertinotti was able to deliver every

time. In

the decisive vote in July, the tally in the Chamber of Deputies was 549

in

favor, 4 against. The Unione and the Berlusconi opposition were in

complete

agreement – but for four dissenters. These were from “Sinistra

Critica,” which

poses as a left opposition within the PRC, constituted of largely of

supporters

of the United Secretariat of the Fourth International (USec), followers

of the

late Ernest Mandel, and the International Socialist Tendency,

supporters of the

line of the late Tony Cliff, who considered the Soviet Union “state

capitalist.”

In

the Senate, however, the margin between center-left and center-right is

a mere

two votes (158 to 156), so the bourgeois popular front needs all 27 PRC

senators on every vote – no dissents, no absentions, no absences. If

the Prodi

regime loses a single key vote – such as the proposal to continue the

war in

Afghanistan – it could fall, opening the possibility for Berlusconi

& Co.

to return to power. So the Unione has posed every key vote in

parliament as a

motion of confidence in the government. Bertinotti and Franco Giordano

(the new

PRC secretary) use this device to cajole and threaten their left-wing

critics,

who have obliged them every time. In advance of the Senate vote on the

Afghan

“mission” last July eight senators – from Sinistra Critica, the PRC

majority,

the Greens, and the PdCI – issued a proclamation: “Non alla guerra,

senza se e

senza ma!” (“No to the War, Without Ifs or Buts!” – the main slogan of

the

antiwar movement). This pacifist slogan masks the need to fight the imperialist

war with class war by mobilizing the power of the

proletariat to defeat

“their own” bourgeoisie. As it turned out, however, all eight

self-styled “left

oppositionists” ended up obeying the discipline of the popular front

and voting for the war on Afghanistan.

While

Mandelites and Cliffites formally claim to be Marxists and, to one or

another

degree, cite Leon Trotsky, in reality they seek to drag Trotsky’s name

and the

revolutionary Marxism it stands for through the mud of class

collaboration.

From Brasília to Rome, these groups join repressive capitalist

regimes,

including (where they can) as cabinet ministers, while calling

themselves

revolutionaries. From the beginning of the 20th century, this kind of

“ministerial socialism” was derided by genuine Marxists. These

reformist anti-Trotskyists

are following in the footsteps of Stalinism and Social Democracy.

Throughout

his life Trotsky resolutely opposed the popular front, whether in power

or out,

as a tool of a weakened capitalist class that seeks to enlist the

working class

– through the agency of reformist workers parties – in engineering its

own

defeat. In China in the 1920s, in France and Spain in the 1930s, he

warned that

the popular front prepares the way for disaster for the working class.

Only in

Russia was catastrophe averted – because the Bolshevik Party led by

Lenin and

Trotsky overthrew the popular-front Provisional Government led by

Kerensky and

established a revolutionary workers and peasants government.

Livio

Maitan and the Bitter Fruits of Italian Pabloism

After

Trotsky was assassinated by a Stalinist hireling in August 1940, and

particularly in the aftermath of the Second World War, in which many

leading

Trotskyist militants were murdered by the fascists and the Stalinists,

the

Fourth International leadership fell to less experienced comrades. They

began

to ignore the fundamental lessons of the Bolshevik Revolution.

Ultimately, a liquidationist

program was advanced by Michel Pablo and Ernest Mandel, who under the

impact of

the anti-Soviet Cold War theorized that the Stalinists could be

pressured into

“roughly outlining” a revolutionary policy. Pablo’s conclusion was a

policy of

“deep entrism,” ordering sections of the Fourth International to

dissolve their

own small organizations into the mass Stalinist Communist Parties.

Subsequently, the Pabloites and Mandelites would tail after the

Algerian FLN,

Castro/Guevaraist guerrillaism in Latin America, Red Guards in Mao’s

China –

whatever was the fad in petty-bourgeois radical milieus; in the 1980s,

they

joined NATO social democrats like François Mitterrand in an

anti-Soviet hue and

cry over Afghanistan and Poland.

Livio Maitan

Livio Maitan

What

the Pablo/Mandelites did not do was build independent

Leninist-Trotskyist parties to fight for international socialist

revolution. Pabloism led to the organizational

destruction of

Trotsky’s Fourth International, which the League for the Fourth

International

is dedicated to forging anew. In Italy, where the prewar Trotskyists

had been

decimated by murderous fascist and Stalinist violence, Livio Maitan

(1923-2004)

became a Pabloite leader of international importance, especially after

Pablo

took his liquidationist program to its logical conclusion and joined

the

post-independence bourgeois-nationalist government of Algeria.

In Latin America in the

1960s,

Maitan was instrumental in forcing the parties parties of the United

Secretariat to abandon any pretense of Marxist proletarian orientation

in favor of a disastrous

strategy

of peasant-based guerrilla warfare. The effect was to wreck nuclei of

would-be

Trotskyists across the continent, especially in Argentina, Bolivia and

Peru.

In

Italy, in the 1950s and ’60s, Maitan encouraged supporters of the

Pabloist International and later United Secretariat to bury themselves

deeply in the PCI. As a result,

when

the great explosion of radical youth and working-class struggle took

place in

1968-69, there was no Trotskyist party in Italy that could fight to

lead this

upsurge. Thousands of young militant workers, disgusted with the

instrumental

role the PCI played in propping up the capitalist order, and seeing no

revolutionary alternative because of the liquidationist policies of

Maitan and

the USec, impressionistically styled

themselves as

Maoists, syndicalists or even anarchists – tendencies to which Maitan

then

adapted as well. In his later years Maitan became a close advisor to

Bertinotti, whose introduction to Maitan’s 2002 autobiography, La

Strada

Percorsa (The Road Traveled) is an effusive tribute to the author.

In 1991,

Maitan and his “Bandiera Rossa” organization helped found Bertinotti’s

Rifondazione Comunista – the very party on which the current capitalist

order

in Italy relies.

Sinistra Critica: “Si a la Guerra!”

Today

the popular front’s hold on power in Italy is none too secure, owing to

the

narrow vote margins. In the Senate, Sinistra Critica senator Franco

Turigliatto, a supporter of the USec and longtime aide to Maitan,

justified his

“yes to war” vote in a long-winded speech with the Orwellian title:

“Against

the Italian Intervention in Afghanistan.” Turigliatto admitted that 60

to 70

percent of Italians want Italian troops out of Afghanistan, but he

carried out

his duty for the capitalist ruling class. The publication of

the USec,

had the gall to write of this ploy by the “radical left”: “even though

its

representatives in the Senate voted for the motion of confidence... and

the

financing of the war in Afghanistan, they showed that even a small

minority can

stand up to the government’s policy” (International Viewpoint,

October

2006). They “stood up” by sitting in their parliamentary seats and

voting for

war credits, as the German Social Democrats did on that fateful 4

August 1914!

No Karl Liebknechts here! This is the kind of cynical subterfuge and

outright

lying which fake Marxists trade in, and their betrayal must be

ruthlessly

exposed.

In

the Chamber, where the four “no” votes against Italian participation in

the

occupation of Afghanistan were registered, the Unione has enough of a

majority

so that the votes were not needed. Deputy Salvatore Cannavò of

Sinistra Critica

could take the liberty voting “no.” But this was grandstanding as

Cannavò

remarked that “the ‘objector’ senators have chosen to agree, in an act

of extreme

sacrifice, to vote for the motion of confidence in the government” (Liberazione,

27 July). What a sacrifice! (One deputy in the PRC majority, Paolo

Cacciari,

showed more guts, resigning his seat in protest over the parliamentary

charade

on the Afghanistan vote.) But as the government keeps calling one vote

of

confidence after another, the PRC “left” can’t duck. On the budget,

with its

cutbacks and attack on pensions, Cannavò ended up abstaining on

the law and

then leaving the Chamber during the vote on the motion of confidence

rather

than opposing this anti-working-class law outright. For this timid

dissent, the

PRC tops have threatened to put him on trial, while removing Sinistra

Critica

supporters from all official posts. In the Senate, SCer Turigliatto

voted for

the capitalist cutback budget just as he earlier voted for

imperialist

war.

Break

with the Centrist Tails of the Popular Front . . .

As

Lenin remarked to the March 1917 Bolshevik Party conference, “I hear

that in

Russia there is a trend toward unification . . . with the defensists –

that is

a betrayal of socialism. I think it is better to stand alone like

Liebknecht –

one against a hundred and ten.” Lenin was addressing the party from

exile in

Finland; Trotsky was then in a concentration camp in Canada. The party

was

being misled by Stalin and Kamenev, who were seeking accommodation with

the

Kerensky-led popular front, which stood for “defense of the fatherland”

by

continuing the slaughter of the first imperialist world war. By “stand

alone

like Liebknecht,” Lenin referred to the German Social

Democratic

deputy, Karl Liebknecht, who in December 1914 stood alone in the

Reichstag

against

the whole of the Social Democratic Party and refused to vote war

credits for

the war of the Kaiser and the industrialists like Krupp. Today,

millions of

Italian workers would be willing to stand up to the capitalists, yet

they are

bound to the bourgeoisie via the popular front imposed on them

primarily by the

PRC and sellout union bureaucrats.

Protester's sign in

November 17 strike/protest against popular-front budget law denounces

prime minister Prodi. (Photo:

Luca Bruno/AP)

Protester's sign in

November 17 strike/protest against popular-front budget law denounces

prime minister Prodi. (Photo:

Luca Bruno/AP)

With

the Unione in power, the left parties have generally shifted to the

right.

Following the April election, the

ex-Stalinists of the DS vowed to complete their transmogrification into

mainstream bourgeois politicians by joining with the ex-Christian

Democrats of

the Margherita to form a Democratic Party. The Rifondazione Comunista

tops are

communists in name only. Bertinotti is preparing to ditch the reference

to

communism by launching a magazine, Alternative per il socialismo,

which

he says represents a fundamental “svolta,” or turning point,

akin to the

PCI’s turn to “Eurocommunism” in the late ’70s (Corriere della Sera,

20

December). Sinistra Critica is if anything worse yet, because it tries

to sully

the name of Trotsky with its betrayals. While the Mandelites and

Cliffites of

SC try to hang on to positions of influence in the PRC, others with

equally

rotten reformist politics like the FalceMartello (Hammer and Sickle)

group,

part of the tendency founded by the late Ted Grant, strike a slightly

more

militant pose having no parliamentary seats to lose. But while FM

publishes a

pamphlet against attacks on immigrants in the city of Sassulo, it still

votes

for the PRC which is part of the city council that launched the racist

attacks.

These fans of Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez are as deeply imbedded in

Bertinotti’s

PRC as their Mexican comrades are in the bourgeois PRD of

Andrés Manuel

López Obrador.

As

the “responsibilities” of governing a capitalist state intensify

Rifondazione’s

internal contradictions, various centrist currents have been thrown

into

turmoil. Marco Ferrando, the principal leader of the Progetto Comunista

tendency, was slated to be a Senate candidate for the PRC in the 2006

elections. However, the entire bourgeois media and politicians of right

and

“left” threw a fit over an interview with Ferrando in Corriere

della Sera

(13 February) published under the headline, “‘Shoot at Our Soldiers? A

Right of

the Iraqis.’ Ferrando: Nassiriya Was a Case of Armed Resistance.” What

Ferrando

actually said was that armed struggle against the colonial military

occupation

was just, and that Berlusconi had sent troops to Nassiriya (where they

were

attacked by guerrillas in November 2003, leaving 19 Italian soldiers

and police

dead) because of Italian capitalists’ interest in Iraqi oil. As

politicians

from the DS to the fascist AN howled, the PRC’s Bertinotti abruptly

dumped

Ferrando. Nevertheless, Ferrando called to vote for the PRC in the

April

elections and thus helped install the popular front in office. In

mid-May, on

the eve of Rifondazione’s vote for the Unione government, Progetto

Comunista

broke from the PRC to set up the Movimento Costitutivo del Partito

Comunista

dei Lavoratori (MCPCL – Movement to Constitute a Communist Workers

Party).

Meanwhile,

another part of the Progetto Comunista current objected to Ferrando’s

candidacy

on the grounds that it was arranged behind the backs of the

rank-and-file, and

that he had agreed to vote for a Prodi government. But this grouping,

now

called Progetto Comunista – Rifondare l’Opposizione dei Lavoratori

(PC-Rol –

Communist Project – Refound the Workers Opposition), in typically

opportunist

fashion proposed to the PRC tops that its spokesman, Francesco Ricci,

replace

Ferrando on the ballot. Behind the centrists’ endless maneuvering, the

fact is

that the Proposta/Progetto Comunista current never represented a

revolutionary

opposition, but rather a centrist barnacle on the reformist PRC.

Ferrando

supported Bertinotti in the leadership of Rifondazione Comunista when

it backed

the first (1996-98) Prodi government, which invaded Albania. Ferrando

was fully

prepared to vote for Prodi II, if only Bertinotti had let him . .

. Such are

the

wages of opportunism.

The

various pseudo-Trotskyist groupings in and around Rifondazione

originate in

Pabloism (Sinistra Critica, Progetto Comunista) or other currents

characterized

by ingrained tailism (Cliffites) and deep entrism in reformist mass

parties

(the Grantites were buried in the British Labour Party for half a

century).

They have never fought to build an independent Leninist-Trotskyist

vanguard

party of the proletariat, which was the centerpiece of the founding

program of

Trotsky’s Fourth International. Their maneuverings with Bertinotti and

the PRC

while the latter sustain Prodi I and join the Prodi II governments are

business

as usual for these inveterate opportunists. This is precisely what

Trotsky was

referring to when he condemned centrists who seek to “peddle their

wares in the

shadow of the People's Front.” As Trotsky went on to stress in his July

1936 letter

about the maneuvers of the Spanish POUM: “In

reality,

the People's Front is the main question of proletarian class

strategy

for this epoch. It also offers the best criterion for the difference

between

Bolshevism and Menshevism.”

.

. . to Build a Leninist-Trotskyist Workers Party in Italy

The

left-centrist Lega Trotskista d’Italia (LTd’I – Trotskyist League of

Italy),

part of the International Communist League (ICL) led by the Spartacist

League/U.S., voices a number of correct criticisms of the

pseudo-Trotskyist

milieu that for the last decade and a half has sought to make the

social-democratic Rifondazione Comunista more appetizing to would-be

communist

militants, thereby chaining them to the bourgeois popular front. But

following

the ICL’s own svolta (turnabout) in the mid-1990s, in the

latter-day

Spartacist discourse, these criticisms are accompanied by an obligatory

disquisition on how, due to the collapse of the Soviet Union, the

workers’

consciousness has undergone a qualitative regression:

“But

in contrast to the past, the workers don’t see, even in a partial or

deformed

manner, their struggles as part of the struggle for a socialist

transformation

of the world. In many cases, even the idea that this society is based

on the

class struggle between workers and capitalists is distant.”

–“2006

Elections: No Alternative for the Workers,” Spartaco, March 2006

For

our part, the League for the Fourth International has noted that the

historic

defeat of the proletariat represented by the demise of the

bureaucratically

degenerated/deformed Soviet and East European workers states has had a

real but

uneven effect on the workers’ consciousness. And it has not altered or

rendered

outdated (as the ICL contends) the central thesis of Trotsky’s Fourth

International, that the historical crisis of mankind is reduced to the

crisis

of proletarian revolutionary leadership. In fact, the impact of the

counterrevolutionary destruction of the USSR has been greatest on the

workers’ leaderships and leftist groups claiming to be

revolutionary. Nowhere is

this more

evident than in Italy, particularly over the war. During 2002-03, there

were

not only huge pacifist marches, the working class also sought to fight

against

the war. In February 2003, railroad workers and antiwar activists

blocked rail

lines in northern Italy seeking to prevent the transport of U.S. tanks,

artillery and munitions to the Persian Gulf; when the U.S. launched the

invasion, thousands of Italian workers walked out. Since the beginning

of the

war drive, we in the LFI have fought for workers strike action against

the

imperialist war.

The

ICL on the other hand, especially in the U.S., dismissed our calls for

the

defeat of U.S. imperialism and for workers to “hot cargo” (refuse to

handle)

military goods and for strikes against the war as “rrrevolutionary

phrasemongering.” In Italy, where it was impossible to ignore the

workers’

antiwar actions, the LTd’I briefly raised the call “For Workers Strikes

Against

the War” – but only after (not before) the dramatic battle of

the rails

(Spartaco, June 2003). It has not repeated this since, even

though

Italian workers overwhelmingly continued to oppose the war. Nor has it

raised

the call for concrete workers actions against the war over the

continued

presence of Italian troops in Afghanistan, or the sending of Italian

forces to

Lebanon. (At most it talks vaguely of continuing “class struggle at

home” in

the context of imperialist war, which could mean almost anything.) The

ICL

justifies its refusal by arguing that strikes against the war would be

tantamount to calling for revolution, and since “the workers don’t see

… their

struggles as part of the struggle for a socialist transformation of the

world,”

not even in a partial or deformed way, such calls are empty. Except

Italian

workers actually do it.

The

ICL is not alone in claiming that Trotsky’s argument that “the

historical

crisis of mankind is reduced to the crisis of the revolutionary

leadership” has

become “insufficient” (see “In Defense of the Transitional Program,” The

Internationalist No. 5, April-May 1998). The Mandelites, Cliffites

and

others use the thesis of a retrogression in workers’ consciousness in

order to

justify their capitulations to the reformist misleaders, and to abandon

any

reference to Trotskyism; the latter-day Spartacists use the same

argument to

justify abstention from the class struggle. At bottom this revisionism

is based

on anti-Leninist conceptions of the relationship of the party to the

class. The

Mandelites and Cliffites (the latter most explicitly) reject Lenin’s

thesis, in What Is To Be Done? that revolutionary consciousness

is

brought to the

working class from outside the framework of the daily struggles with

the

bosses, which by themselves at most generate trade-union consciousness.

The ICL

puts forward an idealist conception. As we wrote: “They see the role of

the party as

that of

missionaries rather than the advance guard of the proletariat, which

develops

the mentality of the workers through its sharp programmatic

intervention in the

class struggle” (“In Defense of the Transitional Program”).

In

2001-03, Italy was racked by militant youth, worker and antiwar

struggles on a

massive scale: July 2001, Genova uprising against the G8

imperialist

rulers’ conclave; April 2002, 13 million-strong general strike;

February

2003, 3 million march against Iraq war, workers block “trains of

death”; October

2003, 10 million-strong general strike against attacks on

pensions; March

2004, 1 million march against war. Today, Italy is still involved

in

imperialist war and the attacks on workers’ livelihoods continue, but

protests

are far smaller. What changed? A new regression in workers’

consciousness? No,

what happened is that the PRC, which during 2001-05 had opted to

support

“social struggles,” decided at its 2005 conference to sign on with the

Unione

popular front. Its reformist and centrist hangers-on were dragged along

in its

wake. Today as in the past, Italy probably has more self-proclaimed

revolutionaries and syndicalist trade-unionists per square kilometer

than anywhere

else on the planet, yet Italian capitalism remains intact. What’s

key is the fight

for revolutionary leadership.

This

requires ruthless exposure of the betrayals not only of the PRC and

union

misleaders, but also by smaller reformist and centrist currents that

tail after

them. It is necessary to intervene in struggles of workers and the

oppressed

with a transitional program going beyond the limits of capitalism: for

a

sliding scale of wages and hours, to combat mass unemployment and

inflation;

for full citizenship for all immigrants, for dissolving the CPT

detention camps

and for workers mobilization against anti-immigrant attacks; for

workers

defense guards against fascist provocations and workers strikes against

imperialist war. The Berlusconi gang will not be defeated at the ballot

box by

a wretched popular front which carries out the same anti-worker

policies,

practically to the letter. The capitalist class has never given up

power

voluntarily, no matter how many so-called communist deputies get

elected.

Proletarian power will not come from bourgeois parliaments, but our own

working-class organizations – unions, factory committees, defense

guards and

ultimately workers councils. The starting point is to gather the most

militant

and conscious workers in building the nucleus of a

Bolshevik-internationalist

party, as part of the struggle to reforge an authentically Trotskyist

Fourth

International. n

To contact the Internationalist Group and the League for the Fourth International, send e-mail to: internationalistgroup@msn.com