January 2007

Protest in Mexico City against bloody cop attack on Oaxaca teachers, June 14.

(Photo: Eduardo Verdugo/AP)

Forge a Revolutionary Workers Party!

As 2007 dawns, Mexico is

still reeling from ten months of sharp class conflict. A new government

has

taken office vowing to employ “the full weight of the state” against

those who

defy it. Felipe Calderón, the reactionary president imposed by

the Federal

Elections Tribunal over massive protests, wants above all to assure

Wall Street

and Washington that he will “preserve economic stability.” The

appetites of the

head of the right-wing National Action Party (PAN) for a “strong state”

are

evident, but he comes into office as the weakest government of any in

recent

history. Not only did protesters shut down the capital’s main square

and main

thoroughfare for six weeks last summer protesting electoral fraud,

workers,

peasants and teachers repeatedly defeated police and troops in a series

of

pitched battles over the last year. Although a six-month mass strike in

the

southern state of Oaxaca ended with an eruption of cop violence and

hundreds of

arrests, the tens of thousands of strikers are unbowed. The dramatic

clashes of

2006 have sown the seeds of revolution, as the strikes of 1906-07

signaled the

coming of the Mexican Revolution of 1910. But the key element for a

victorious

outcome is absent: a revolutionary vanguard with the program and

determination

to sweep away the inhuman exploitation and mass poverty of capitalism

and set

out on the road of international socialist revolution.

The response of Mexico’s

rulers to last year’s unrest has been rampant militarization. Twice in

recent

months, the government of outgoing president Vicente Fox surrounded

Congress

with a ring of metal barricades and thousands of troops and riot police

and

kept the area sealed off for days. Calderón was sworn in as head

of state by a

military officer at a private midnight ceremony in the presidential

residence,

Los Pinos. He slipped into Congress the next day by a back door for an

official

appearance that lasted less than five minutes, then ducked out again.

The new ruler

started off the new year by donning a military cap and jacket as

commander in

chief of the armed forces to review Mexican Army units in

Michoacán, where they

are allegedly fighting drug traffickers. He simultaneously launched a

“Plan

Tijuana,” supposedly directed at the drug kingpins who dominate the

city under

Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) mayor Jorge Hank Rhon. But the

plan

mainly consisted of searching vehicles and carrying out military

patrols in

neighborhoods considered to be “conflict” zones looking for stolen

autos,

contraband and networks for funneling undocumented immigrants across

the border

to the United States. In other words, it was really about getting the

population used to police-state controls.

Mexican

Federal Police patrol Colonial Libertad in Tijuana, accustoming the

population to police-state controls. (Photo: Don Bartletti/Los

Angeles Times)

Mexican

Federal Police patrol Colonial Libertad in Tijuana, accustoming the

population to police-state controls. (Photo: Don Bartletti/Los

Angeles Times)

Calderón is also

militarizing his administration. Among the officials participating in

his

Michoacán military review were the new minister of the interior

(Gobernación),

Francisco Ramírez Acuña, who gained notoriety as governor

of Jalisco by his

heavy-handed jailing of anti-globalization protesters; the new attorney

general, Eduardo Medina Mora, formerly head of the Federal Preventive

Police

(PFP); and Michoacán governor Lázaro Cárdenas

Batel, who last April sent state

police to join the PFP in assaulting striking steel workers in the city

named

after his grandfather, President Lázaro Cárdenas

Ríos. Now the administration

plans to fuse the PFP and Federal Investigative Agency to create a

“super-police” under the general commanding the combined

police/military force

in Oaxaca, Ardelio Vargas. The purpose of this operation is to provide

security

and “stability” for capital. Calderón explained to the

convention of the

Mexican Stock Market last October, “As head of the federal executive I

am

committed to creating an environment favoring investment and

employment…,

promoting competitiveness,” etc. After the media show of going after narcos

and coyotes is over, his beefed up police apparatus

will get

down improving

the business “environment” by repressing workers and other opponents.

In his speech to the stock

marketeers, Calderón vowed to maintain Mexico’s “leading

position in attracting

investment.” Police “reform” is high on the agenda of foreign investors

and

pundits, who may be annoyed by the pervasive corruption and ties to

drug gangs,

but were livid at the spectacle of federal police retreating before

youths

armed with slingshots and “Molotov cocktails” in Oaxaca last November

2.

Keeping Wall Street money men happy is uppermost in the minds of

Mexico’s

rulers in recent years, as imperialist bankers have bought up 80

percent of the

country’s financial institutions. What they are really after is

grabbing

Mexico’s enormous oil (nationalized by President Cárdenas in

1938) and

hydroelectric resources. This would require an amendment to Mexico’s

constitution

and likely provoke a battle royal with workers unions and nationalist

politicians. Speaking out of one side of his mouth, Calderón

tells

international high finance that he will accommodate them (a U.S. Energy

Information Agency report says the new president will “allow private

companies

to participate in new energy projects”) while for domestic consumption

he vows

he won’t privatize oil or electricity. The double talk covers a

contradiction

which cannot be maintained much longer.

The imperialists are

getting impatient with the pace of economic “reform” in Mexico and are

demanding drastic action. Last fall, the British Economist (18

November

2006) published a special survey on Mexico under the title, “Time to

Wake Up.”

It called on Calderón to be “far bolder than his predecessor in

tackling the

many vestiges of the old order that are still holding the country

back.” These

“vestiges” include going after “monopoly power . . . from the teachers’

union

to Pemex, the state oil monopoly.” But like Fox before him, the

technocratic

president tied to the ultra-rightist Catholic secret society El Yunque

hesitates to tear down Mexico’s corporatist structure all at once, for

fear

that the country could come apart. Other provocative demands by the

international bankers include extending the sales tax (IVA) to medicine

– which

Fox tried but failed to push through Congress – and ending subsidies of

basic

food products, like tortillas. In November, the government raised the

price of

subsidized milk by 28 percent, while in December it increased the

minimum wage

by less than 2 pesos (20 cents) a day, not enough to buy one egg and

one

aspirin. Now the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

is

telling Mexico’s government to privatize the ejidos, land

belonging to

peasant and Indian communities. Such calls are designed to provoke a

revolt.

The main thing holding it

off so far has been the porous border to the U.S., which acted as a

kind of

safety valve: instead of protesting, the dispossessed headed north. Now

the

border is being closed, and pressure is building toward a social

explosion. The

North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) has devastated Mexican

agriculture.

Millions of poor peasants have been forced off their land because their

corn

cannot compete on the market with the (highly subsidized) U.S. grains.

As

trainloads of corn from Iowa headed south on the (now U.S.-owned)

railroads to

Mexico, Mexican peasants headed north to Iowa to find work in packing

plants.

Now the situation in the countryside is about to become even more

dramatic, as

tariffs on imported corn are due to fall from 27 percent to 16 percent

this

month, and to 0 by January 2008. For a time the maquiladora

free-trade

zone plants managed to absorb many young workers producing electronic

goods,

auto parts and clothing for the giant U.S. market. But in the last

several

years hundreds of thousands of maquiladora workers have lost

their jobs

as fly-by-night entrepreneurs shut down plants to head for even

lower-wage

havens, particularly China. So while racist reactionaries in the United

States

froth about Mexican workers “stealing American jobs,” their

counterparts south

of the border rail against the Chinese deformed workers state for

“stealing

Mexican jobs.”

For more than six decades,

the one-party regime of the PRI was able to maintain “economic

stability” with

a capitalist economy in which key sectors (energy, heavy industry,

transport,

finance) were in the hands of the state. They fostered the growth of a

domestic

capitalist class with cheap energy prices and cheap credit, while

keeping a lid

on labor protest with corporatist “unions” which acted as labor cops

for the

bosses. Leaders were integrated into the PRI-government apparatus,

workers in

key industries were thrown some crumbs in the form of job security and

social

benefits, while wages were kept low and dissidents brutally repressed.

Over the

last two and a half decades, PRI presidents De la Madrid, Salinas and

Zedillo

and then Fox of the PAN have been dismantling this semi-bonapartist

regime bit

by bit. Salinas sold off more than 1,200 state-owned companies to his

cronies,

making instant billionaires of some and turning Carlos Slim (owner of

the

privatized Teléfonos de México) into the third-richest

man in the world. As the

super-rich wallow in dollars, the already miserable incomes of Mexican

are

falling while social security is gutted. Mexico is hurtling toward a

crisis.

The only question is the outcome.

“Popular Democracy” or

Workers Revolution

The “president elect” imposed by the

Federal Elections Tribunal, Felipe Calderón, wears a military

cap while reviewing the troops together with his secretary of war,

Guillermo Galván. (Photo: Guillermo Arias/AP)

The “president elect” imposed by the

Federal Elections Tribunal, Felipe Calderón, wears a military

cap while reviewing the troops together with his secretary of war,

Guillermo Galván. (Photo: Guillermo Arias/AP)

Beginning with the deaths

of 65 coal miners in the state of Coahuila last February, Mexico has

been

convulsed by almost uninterrupted labor unrest. When Fox’s labor

minister tried

to remove the head of the corporatist miners “union,” Napoleón

Gómez Urrutia,

as punishment for slipping the leash and talking of “industrial

homocide” at

the Pasta de Conchos mine, more than 300,000 mine and metal workers

walked out

in protest. Gómez Urrutia called it off after a few days, but

steel workers at

the Sicartsa-Las Truchas plant in Lázaro Cárdenas

(Michoacán) and copper miners

at Cananea and Nacozari (Sonora) stayed out on strike for months. The

miners

lost and were forced back to work with hundreds fired, but the steel

strikers

won, with an 8 percent wage increase, full pay for strike days, a

US$700 bonus

and increased benefits. This victory was a dramatic demonstration of

the

workers’ power, having occupied the plant and defended it by driving

off an

assault by federal, state and local police along with marines on April

20, at a

cost of 2 strikers killed. But the impact of the strike victory

remained

limited as the struggle was confined to strictly trade-union bounds.

The cop-military attack on

the Sicartsa plant was followed two weeks later by a brutal police

assault on

peasants and townspeople in San Salvador Atenco, in Mexico state near

the

Federal District. It began with the arrest of some flower sellers by

police of

the town of Texcoco, whose PRD mayor wanted to ban street vendors in

order to

make way for a Wal-Mart store. There, too, the police were driven out,

only to

return with thousands of federal and

state police who brutally beat and arrested hundreds. Several dozen

women

protesters were sexually molested and raped after being detained. This

set off

worldwide protests initiated by the “Other Campaign” of the Zapatista

National

Liberation Army (EZLN). But by far the largest struggle was that

launched by

striking teachers in the state of Oaxaca, which began in late May and

lasted

until the end of November. On June 14, the murderous state governor,

Ulises

Ruiz Ortiz, ordered an army of several thousand riot police to evict a

strikers’ encampment (plantón) in the center of Oaxaca

city. But the

40,000 teachers fought back and drove out the cop attackers. From then

until

the PFP invaded at the end of October, the state capital was in the

hands of

the strikers and their allies of the Popular Assembly of the Peoples of

Oaxaca

(APPO).

The story of that

convulsive struggle is recounted in a series of articles in this issue

and the previous issue of The Internationalist (No. 24, Summer

2005). Following the violent arrest of hundreds and imposition of a de

facto

state of siege in Oaxaca on November 25, the focal point of

mobilization has

shifted to the demand for immediate release of the detainees, several dozen of whom are still in jail, and

dropping the trumped-up charges. More than 20 strike supporters were

killed

over the course of the six-month battle. But while the PRI

governor-assassin

Ruiz Ortiz crows victory and his PAN allies in Mexico City proclaim

that it’s

all over, the working, poor and indigenous people of Oaxaca continue to

fight.

On January 6, “Three Kings Day,” when children in Mexico traditionally

receive

presents, the APPO held an event to give toys to the children whose

parents are

behind bars, prisoners in the class war. Typically, the state

government sent

riot cops to keep the kids out of the Plaza of Santo Domingo, claiming

the need

to “provide security for tourists.” Hundreds of children showed up

anyway, some

with signs saying the best present would be for Ruiz to leave (La

Jornada,

7 January).

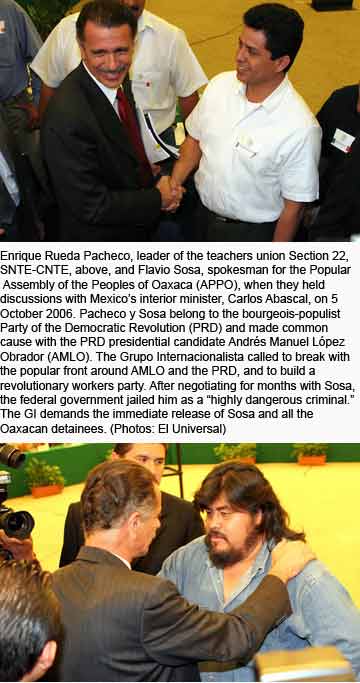

While keeping up the

struggle, it is time to take stock and draw the lessons of more than

half a

year of hard combat. What are those lessons? The APPO leaders who have

not been

jailed are focused on getting their comrades out of prison,

particularly APPO

spokesman Flavio Sosa, a demand that should be taken up by the entire

workers

movement, in Mexico and internationally. Militant sectors want to

settle

accounts with Enrique Rueda Pacheco, the leader of the 70,000-strong

Oaxaca

teachers union, Section 22, SNTE-CNTE, who broke ranks and ordered

strikers

back to work at the beginning of November, leaving APPO supporters

alone on the

barricades. Thousands of teachers refused to obey and now rightly want

to throw

out Pacheco for strikebreaking. At the same time, the leader of the

national

corporatist teachers “union” (SNTE), Elba Esther Gordillo, has cashed

in on her

crucial electoral support to Calderón, placing her agents in

control of the

secretariat of public education, and setting up a new Section 59 in

Oaxaca made

up of teachers who scabbed during the strike. Meanwhile, combative

students and

youth who played a key role in the victorious November 2 defense of

Oaxaca

University sharply denounce the APPO leaders for abandoning them after

November

25.

The

militants’ complaints

are utterly valid, but by posing the issue in essentially personal

terms, on

the terrain of simple militancy vs. betrayal, they fail to address the

political reasons for the “moderates” stab in the back. The basic fact

is that

the leaders both of the APPO (Sosa) and of the Oaxaca teachers union

(Rueda

Pacheco), as well as of the new scab section of the national SNTE, all

are

supporters of the bourgeois populist Party of the Democratic Revolution.

Sosa, while he may affect the look of a student radical, is a national

counselor of the PRD, who in 2000 even joined those PRDers calling to

vote for

the rightist Fox as a “lesser evil” to the PRI. While they engaged in

combative

tactics locally, nationally they looked to the PRD. APPO’s support to

PRD

presidential candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador in the

July 2 elections was

seen by many Oaxaca strikers as a “tactical” move against Ulises Ruiz

Ortiz: a

vote for AMLO against URO. But for the APPO leaders it was strategic.

When they

traveled to the capital for negotiations, they sat down in the PRD plantón

in the Mexico City Zócalo. And just as López Obrador

didn’t intend his street

protests to challenge the bourgeois state, which they didn’t, the

Oaxacan

leaders quite consciously never raised demands going beyond the limits

of

capitalism.

The

militants’ complaints

are utterly valid, but by posing the issue in essentially personal

terms, on

the terrain of simple militancy vs. betrayal, they fail to address the

political reasons for the “moderates” stab in the back. The basic fact

is that

the leaders both of the APPO (Sosa) and of the Oaxaca teachers union

(Rueda

Pacheco), as well as of the new scab section of the national SNTE, all

are

supporters of the bourgeois populist Party of the Democratic Revolution.

Sosa, while he may affect the look of a student radical, is a national

counselor of the PRD, who in 2000 even joined those PRDers calling to

vote for

the rightist Fox as a “lesser evil” to the PRI. While they engaged in

combative

tactics locally, nationally they looked to the PRD. APPO’s support to

PRD

presidential candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador in the

July 2 elections was

seen by many Oaxaca strikers as a “tactical” move against Ulises Ruiz

Ortiz: a

vote for AMLO against URO. But for the APPO leaders it was strategic.

When they

traveled to the capital for negotiations, they sat down in the PRD plantón

in the Mexico City Zócalo. And just as López Obrador

didn’t intend his street

protests to challenge the bourgeois state, which they didn’t, the

Oaxacan

leaders quite consciously never raised demands going beyond the limits

of

capitalism.

Yet the pitched battles in

the streets of Oaxaca that defeated police attacks, the erection of

thousands

of barricades throughout the city, the takeover of several dozen towns

around

the state by striking teachers, the teachers’ “police” squads that kept

order

in the occupied state capital – these aspects of a hard-fought class

struggle

did begin to present an implicit challenge to the capitalist

regime. But

they lacked an explicit revolutionary political perspective. Many

radicals

seized upon these initial steps to present a picture of the struggle in

Oaxaca

as if it were already a revolutionary situation, or on the

verge of

becoming one. This make-believe vision was synthesized in the

propaganda that

circled the globe about a Oaxaca Commune. We warned (see “A Oaxaca

Commune?”

page 36) that this substituted fantasy for fact, and that in any case,

the goal

of Marxists would not be an isolated commune in the most economically

impoverished state of Mexico but a revolutionary proletarian

mobilization

throughout the country and particularly in the capital. We also

emphasized that

those who equated the Oaxaca struggle with the 1871 Paris Commune in

terms of

“democracy” misread the class nature of the latter, which

Marxists from

Marx and Engels to Lenin and Trotsky hailed as the first workers

government

in history.

In the aftermath of

November 25, there have been different responses on the radical left.

Some,

like the Liga de Trabajadores por el Socialismo (Socialist Workers

League) have

simply kept on with the fiction of a Oaxaca Commune, calling it “An

Initial

Revolutionary Attempt” and saying it’s necessary to continue onward and

upward

from this “new stage in the class struggle” (in its dossier, “Crisis of

the

Regime and Lessons of the Oaxaca Commune,” 29-31 December 2006). This

misses

the fundamental point that the roiling mass strike in Oaxaca was

defeated not

by bloody repression, although that was very real, but because the

political

perspective of the APPO and Section 22 leaders had taken them to a

dead-end.

APPO supporters came out by the thousands and defeated the PFP on

November 2,

but following the November 25 police attack they did not come out to

defend

Radio APPO a second time. Why not? Not because they lacked courage and

the will

to fight. They showed that over and over through half a year of

battles. It was

because their leaders had shown them no way forward. Would they

endlessly go up

against the tanquetas (armored personnel carriers) with

slingshots and

stones until the militarized police carried a large-scale massacre with

live

ammunition? What kind of a perspective is that?

Another current, the

Militant tendency, flatly proclaimed a defeat, writing laconically,

“The

Commune of Oaxaca reached its end” (“Lessons of Oaxaca,” Militante,

December 2006). Similar to the LTS, Militante continues to insist that

the APPO

represented “embryos of soviets” – leaving aside the fact that, while

various

unions participated in the APPO, it was not based on the

proletariat,

but rather represented a multi-class conglomeration of the various

sectors in

struggle (teachers, indigenous peoples, students). Militante says,

rightly that

the alternative was revolution or counterrevolution, and that the

responsibility lies with the leadership. According to them, Pacheco

betrayed,

while Sosa, having only an “empiricist” program, “unfortunately wasn’t

up to

the task.” How’s that for a “Marxist” explanation! What Militante wants

to

sidestep is the fact that both Pacheco and Sosa, and the rest of the

APPO

leadership and most of the teachers union tops, supported the PRD.

And

the reason for this omission is simple: Militante poses as the “Marxist

tendency” of this bourgeois party. They criticize “APPO and

AMLO” for

not calling for a united front against repression and pushing for “an

insurrectionary general strike”! How could they?! Looking to a

bourgeois

politician to call a workers uprising only creates dangerous illusions.

And for

its part, Militante gave political support to both APPO and AMLO.

The largest left-wing

political tendency active in the struggle in Oaxaca was the Communist

Party of

Mexico (Marxist-Leninist) and its Revolutionary Popular Front, which

had

supporters in the leadership both of the APPO and the teachers’ Section

22.

When the bourgeoisie called on APPO leaders to rein in the “radicals,”

the FPR

was who they had in mind. The PCM(m-l) is an aggressively Stalinist

party,

hailing “the immortal scientific ideology of Marx, Engels, Lenin and

Stalin”

and prominently displaying the portrait of the man Leon Trotsky

accurately

described “the great organizer of defeats” in the zócalos of

Oaxaca and Mexico

City. With the radicalization of struggles by Mexican workers and youth

in

recent years, notably the 1999 National University (UNAM) strike and

2004

mobilization by Social Security workers, and in 2006 the mine and metal

workers’ and Oaxacan teachers’ struggles, the PCM has often struck a

combative

pose. Its posters declare, “For the Victory of the Proletarian

Revolution” and

denounce capitalism. But at bottom, its political program is the same

old

Stalinist-Menshevik line of a “two-stage” revolution, in which the

first stage

is (bourgeois) democratic. Thus whatever their red flags and posters

may

suggest, these Stalinists are not fighting for workers revolution

in the

here and now.

A recent pamphlet by the

PCM(m-l) and FPR, Considerations on the Revolutionary-Democratic

Process of

the Peoples of Oaxaca (November 2006) interestingly had a first

edition

referring in the introduction to a “Commune that is questioning the

bases of

the system of domination” by the capitalist ruling class, while in the

second

edition the Commune has been disappeared. The document goes on a great

length

describing the ravages of capitalism, which has condemned

three-quarters of the

population of Oaxaca to a life of poverty, massive illiteracy,

denouncing the

“Senate of illustrious bandits” and the “House of merchants.” It talks

of the

“big hotel owners” who are in league with the “old-line caciques”

(political bosses) and “puppets like Felipe Calderón.” But while

it talks of

the “fascists” PRI-AN coalition, and of the “inconsistency of the

social-traitors of the PRD,” it pointedly does not criticize

López Obrador.

Rather than attacking the capitalist state, it refers to the “financial

oligarchy and its state.” And it ends up calling for a “new popular

democratic

republic based on the power of the masses through their popular

assemblies.” In

other words, their operational program is for a bourgeois

republic

governed by an equivalent of the APPO.

For a

Leninist-Trotskyist

Workers Party

Supporters of the Popular Assembly of the

Peoples of Oaxaca (APPO) confront federal police on November 20.

Forging a revolutionary

proletarian leadership is key.

Supporters of the Popular Assembly of the

Peoples of Oaxaca (APPO) confront federal police on November 20.

Forging a revolutionary

proletarian leadership is key.

(Photo: El Universal)

The various tendencies of

the centrist and reformist Mexican left adopt a fundamentally

anti-Marxist view

of the relationship between democratic and socialist struggles. All of

them

call for a new constituent assembly or revolutionary convention,

harking back

to the Mexican Revolution of 1910-1917. And their identification of

“people’s

assemblies” with soviets, the organs of proletarian rule in

the Russian

Revolution, is common to the vast majority of the left in Latin

America. When a

“National and Indigenous Peoples’ Assembly” was formed in Bolivia at

the height

of the 2005 worker-peasant uprising, a chorus of ostensibly

revolutionary

leftists proclaimed this APNO to be “soviets on the altiplano.” That

body

turned out to be stillborn, as we in the League for the Fourth

International

pointed out at the time, and was never more than a cartel of

left-talking bureaucrats.

So when the APPO in Oaxaca took shape with undeniable mass support,

those who

were disappointed in Bolivia took heart and again proclaimed the advent

of

“soviets,” this time in the indigenous heartland of Mexico. This disoriented

the struggle by implying that what was needed was simply to intensify

and

radicalize the APPO’s struggle instead of transforming and extending it

to the

powerful industrial proletariat.

As in every class battle,

the question of leadership is key. Militante proclaims that “this

defeat has

provoked the demoralization of the Oaxacan masses,” when these

pseudo-Trotskyists are actually describing their own demoralization.

The

struggle in Oaxaca suffered a serious setback and temporary defeat, but

it

could flare up again tomorrow. What the Oaxacan masses require is a

vanguard

with a proletarian revolutionary program instead of all the talk about

an

amorphous “people” including sectors of the bourgeoisie. Just before

the

crackdown in Oaxaca, Zapatista Subcomandante/Delegado Zero Marcos

declared, “We

are on the eve of a great uprising or a civil war” (La Jornada,

24

November). After the repression of November 25, Juchitecan painter

Francisco

Toledo said he felt Oaxaca is “almost on the verge of a civil war” and

that the

“Oaxacan political class has to disappear in order to change the

situation in

the state” (La Jornada, 4 December 2006). Today

the immediate issue posed is to free the Oaxacan detainees.

In Spain in the 1930s, the struggle to free thousands of Asturian

miners imprisoned

after the failed uprising of 1934 was a key factor leading to the Civil

War of

1936-39. But that struggle was hijacked and subjugated to the

bourgeoisie

through the Popular Front.

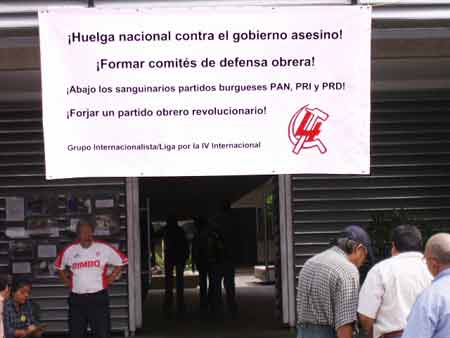

Banner of Grupo

Internacionalista at November 11 rally by SITUAM (Union of Workers of

the Metropolitan Autonomous University) in Mexico City in defense of

Oaxaca teachers: “For a

National Strike Against the Murderous Government! Form Workers Defense

Committees! Down With the Bloody Bourgeois Parties PAN, PRI and PRD!

Forge a Revolutionary Workers Party!” (Photo: El

Internacionalista)

Banner of Grupo

Internacionalista at November 11 rally by SITUAM (Union of Workers of

the Metropolitan Autonomous University) in Mexico City in defense of

Oaxaca teachers: “For a

National Strike Against the Murderous Government! Form Workers Defense

Committees! Down With the Bloody Bourgeois Parties PAN, PRI and PRD!

Forge a Revolutionary Workers Party!” (Photo: El

Internacionalista)

The Grupo Internacionalista

has called repeatedly to break from the popular front around

López Obrador and

the PRD, just as we warned for years that the Cárdenas popular

front was

diverting workers from organizing a class struggle against the PRI

regime.

Contrary to those (such as the Grupo Espartaquista de Mexico) who deny

the

existence of a popular front in Mexico, this popular front has now been

formally constituted with the signing of a document of “strategic

alliance”

between the “independent” pro-PRD unions, several peasant groups and

López

Obrador’s Broad Progressive Front (FAP), which including the PRD, the

Party of

Labor (PT) and the Democratic Convergence, all of them bourgeois

parties. As

new struggles loom, over Calderón’s plans for privatization of

electrical

energy for example, it will be crucial to call on the unions, such as

the SME

(Mexican Electrical Workers Union), to break from the popular front

with AMLO

and the PRD, and to instead fight to build a revolutionary workers

party.

After the battle of Sicartsa and throughout the struggle in Oaxaca, we

called

for the formation of workers defense committees against the

repression

ordered by the PAN, PRI and PRD. As the SNTE led by Gordillo tries to

victimize

Oaxacan teachers for their courageous strike, the GI calls on teachers

and

workers throughout the country to break the corporatist straitjacket by

building unions with class-struggle leaderships, separate from and

opposed to

all the bourgeois parties.

The reverse suffered by the

Oaxacan masses is the result above all of the bourgeois-democratic

program of

their leaders which was incapable of leading them to victory. It is

necessary

to politically rearm to go forward. This is an inevitable part of every

serious

class struggle. As Karl Marx wrote about the French workers’ struggles

of the

mid-19th century:

“Bourgeois

revolutions,

like those of the eighteenth century, storm more swiftly from success

to

success . . . . On the other hand, proletarian revolutions, like those

of the

nineteenth century, constantly criticize themselves, constantly

interrupt

themselves in their own course, return to the apparently accomplished,

in order

to begin anew; they deride with cruel thoroughness the half-measures,

weaknesses, and paltriness of their first attempts, seem to throw down

their

opponents only so the latter may draw new strength from the earth and

rise

before them again more gigantic than ever, recoil constantly from the

indefinite colossalness of their own goals – until a situation is

created which

makes all turning back impossible…”

–Karl Marx, The

Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon (1852)

The Trotskyists of the

Grupo Internacionalista insisted from the beginning on the need to

place the

struggle on a firm class basis and extend it to the “heavy

battalions”

of Mexico’s working class. The goal cannot be limited to “democracy,”

however

popular or even revolutionary this is made out to be. Even if the

murderous

governor of Oaxaca were dumped, even if the “neo-liberal” policies of

recent

Mexican governments were replaced (and AMLO’s program was only for

“neo-liberalism with a human face”), the teachers and indigenous

peoples of

Oaxaca would still be condemned to a life of poverty and oppression, as

they

were for decades under the PRI. The goal today, not in the distant

future, must

be to organize to prepare a workers revolution, from Oaxaca to

Mexico

City to the heart of imperialism. And that requires the leadership of

an

internationalist, revolutionary workers party, built on the program of

permanent revolution and tempered through intervention in the class

struggle

and the fight to forge Trotsky’s Fourth International anew as the world

party

of socialist revolution. n

To contact the Internationalist Group and the League for the Fourth International, send e-mail to: internationalistgroup@msn.com