October 2015

Women’s Liberation and the Class Line

A Voyage of Discovery and Rediscovery

By Marjorie Stamberg

Marjorie speaking at 28 November 2015 protest in New York City, the day after a gunman attacked an abortion clinic in Colorado, killing three people and wounding nine. The Internationalist leaflet called “for defenders of women and all oppressed groups to have adequate means of protecting themselves, exercising their right to organized armed self-defense, and for mass clinic defense to sweep away the anti-abortion thugs.” (Internationalist photo)

We print here the text, edited for publication, of a presentation by our comrade Marjorie Stamberg to the New York Marxist study group of the Internationalist Group on 29 October 2015. Her talk was part of a series on the topic of “Marxism and Women’s Liberation.”

Reflecting on Charlie Brover’s talk last week, he spoke of the importance of Friedrich Engels’ book Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State to the development of the women’s liberation movement, or what they call “second wave radical feminism,” the first wave being the women’s suffrage movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Specifically, Charlie noted Engels’ discovery that the oppression of women and the patriarchy evolved out of the development of private property, and its locus was the family, integral to the capitalist social and economic system. This revelation was highly controversial then, and still is today.

An important point I want to make in this chronology – which is key to understanding this story – is that we were not feminists first, who were won to revolutionary communism. For a lot of us, we were revolutionaries first, who saw the need to fight for women’s liberation and because of that were won to feminism – and then, for some of us, as we saw what it meant in practice, we went from feminism to genuine Marxism. So the movement had rather different origins than the way it is sometimes told.

As an aside, we didn’t see ourselves as “socialist feminists” but as communists, and in fact that whole terminology comes in later, toward the mid-’70s, from social democrats like Barbara Ehrenreich, who went on to become the chairwoman of what we called the Democratic (Party) Socialists of America, the DSA. This is the anti-revolutionary tradition of Max Shachtman, that Bernie Sanders comes out of, and also the leaders of my union, the American Federation of Teachers.

Also, many of us were never attracted by the slogan “sisterhood is powerful,” which is the title of an anthology about the radical women’s movement. We always saw the importance of class and didn’t consider all women our “sisters.” Like Hillary Clinton today, who is no sister to the women workers earning $5 a day in the Haitian sweatshops she set up.

How we found our way to Engels was a voyage of discovery for “movement women.” There would be other “Aha!” moments along the way that would dramatically come to a head on the picket line of a strike at the phone company where “feminism” came into a clash with the class line. So I think that these moments of political discovery are a way to organize this talk.

From left: Clara Zetkin, Rosa Luxemburg and

Alexandra Kollontai

From left: Clara Zetkin, Rosa Luxemburg and

Alexandra KollontaiActually, our “discovery” of Origins was one of rediscovery. This political work had been done before by an earlier generation of revolutionary women leading up to and after the Russian Revolution – Clara Zetkin, Alexandra Kollontai, and others. But that work had been systematically buried by the Stalinists after the political counterrevolution in the Soviet Union and destruction of the Bolshevik Party of Lenin and Trotsky. We had to find it again – this enormous trove of Marxist understanding and writings about the oppression of women. And it had been lost for about four decades.

As I was preparing this talk, I took a look at a 1977 essay by Marlene Dixon, on “The Rise and Demise of Women’s Liberation: A Class Analysis.” Dixon was a professor who was fired by the University of Chicago and then became a kind of soft Maoist and later broke from Marxism. But she had some interesting things to say in this essay. She wrote:

“[T]he Women’s Liberation movement resurrected the ‘woman question’ and rebuilt on a world scale a consciousness of the exploitation and oppression of women. For nearly forty years women had been without a voice to articulate the injustice and brutality of women’s place. For nearly forty years women had been without an instrumentality to fight against their exploitation and oppression.”

Why was there this huge gap? It’s obvious when you think about it, today at least. That gap was due to Stalinism, which perverted and destroyed genuine Marxism. But Dixon doesn’t explain that. She can’t, she was a Maoist Stalinist at the time. And at the time we [“movement women”] didn’t understand Stalinism at all.

Why was the Marxist program on the woman question in particular lost? Because the Stalinists did not hold that the family was the primary unit of women’s oppression. In fact, the opposite, their line was that the family was the “primary fighting unit for socialism” – something to be adulated, like in those awful Stalinist realist posters of the heroic man and woman reaching up to the sky. This line was carried through to Maoism, the Chinese variant of Stalinism, and persisted up to our time. It was the line of Bob Avakian’s Maoist RCP (Revolutionary Communist Party) until events simply overtook them and they had to change it so as not to be completely out of step with modern life.

Black Panther Party leader Elaine

Brown (Photo: Oakland Post,

from Oakland Public Library)

Black Panther Party leader Elaine

Brown (Photo: Oakland Post,

from Oakland Public Library)Another definition: “movement women.” I saw this phrase pop up again in the recent movie by Stanley Nelson, The Black Panthers, Vanguard of the Revolution. Elaine Brown, who was a leading member of the Black Panther Party (BPP) uses the phrase a lot in her memoir, A Taste of Power. “The Movement” was the civil rights movement, and also came to encompass the antiwar movement. There was a radical political culture that exploded in the 1960s, and marked us off from our parents and “establishment” society. It contrasted so sharply with the America of the 1950s, supposedly the “American Dream,” with its typical (white) family with 2.4 (white) children, the little house in the (whites-only) suburb, and the vicious red-baiting of the McCarthy period which drove any ideas of “communism” underground, as it did the Communist Party.

Out of the stultifying Fifties came the Sixties – the Cuban Revolution, the civil rights movement, the massive opposition to the war in Vietnam. People in the U.S. typically become radicalized when they come face to face with the glaring hypocrisy of American society and the contradiction between the democratic ideals taught in school and the very different reality. The realization that the U.S. is not the “cradle of democracy” but a country founded on the bedrock of slavery, and then Jim Crow segregation, and after that modern-day racism, discrimination and now resegregation and mass incarceration. That the United States is not a “good neighbor” to the poorer peoples of the world, but imposes its ravenous imperialist and colonialist agenda through tanks and bombs on the world. Or as Muhammad Ali, then Cassius Clay, was said to have explained his opposition to the war in Vietnam: “No Viet Cong ever called me n----r.”

Building (center) at 3 Thomas

Circle in Washington, D.C., a former embassy, that in the

late 1960s housed the Washington Free Press and

Liberation News Service.

Building (center) at 3 Thomas

Circle in Washington, D.C., a former embassy, that in the

late 1960s housed the Washington Free Press and

Liberation News Service.So we were “movement women.” At this time, I was living in a SNCC-SDS commune in Washington, D.C. I should explain that SNCC was the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, which was the radical wing of the civil rights movement, and SDS was Students for a Democratic Society, which was the mass organization of the New Left. This was only a couple of years after the Civil Rights Act was passed, and up until a few years earlier you had segregated schools, segregated swimming pools, white and “colored” drinking fountains, the whole works. The nation’s capital was basically a Southern city.

So I was living in this SNCC-SDS commune and putting out the first underground paper, The Washington Free Press, because The Movement had rejected all the lies of bourgeois journalism, and we needed our own. This kind of culminated with the April 4, 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King, and the rage that followed it and would spread across the country. That marked the end of the non-violent liberal civil rights movement.

Stanley Nelson documents that in his film on the Panthers. If society could kill the most peaceful, most non-violent leader of black people, there was no room for reform struggle for blacks in America. And for me, living in black Washington – the area east of the Capitol – these were formative experiences. We experienced everyday capitalist exploitation in the ghetto. And when MLK was killed, the exploiters’ price-gouging ghetto stores were burned down. People went into the stores and took what was needed – food from the Safeway, shoe stores and liquor stores went too, everything did.

Black Washington exploded in rage after the April 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. The police fled.

After a day and a half, Army and National Guard troops were brought in to restore bourgeois “order.” (Photo: UPI)

And the cops fled the city – the last image from our commune porch was a burly white cop stuffing a TV he had looted into his squad car and driving away. So for about 48 hours there was no scarcity and no state power. It was a remarkable experience. Until, of course, they brought in the 101st Airborne and the National Guard and bourgeois “order” was restored again. A few years earlier had seen the emergence of the “black power” wing of SNCC, proclaimed by Stokely Carmichael, which would be connected to the political origins of the Black Panther Party. A direct link was Kathleen Cleaver.1 So that was the culture mix.

Shortly after that I was invited to leave Washington and come to New York to be a staff writer on the National Guardian newspaper. The Guardian was the longtime paper of the Communist Party’s “popular front” milieu and was founded to support the 1948 Henry Wallace presidential campaign of the Progressive Party. But by the late 60s, Maoism was the popular variety of Stalinism because many radical youth saw (incorrectly) in Mao Zedong and the “little red book” [of quotations from him] a revolutionary alternative to the staid boring bureaucrats of the USSR. Mao had won a guerilla war, and the People’s Liberation Army had fought, as had Fidel and Che in Cuba. So the paper had to reflect this to attract youth. There was a complete turnover at the Guardian: writers from the New Left and SDS were brought in and the old leftists unceremoniously ejected.

Here is where we begin to get into women’s liberation, and not by accident. By the time I got there, in 1968, we as “movement women” were beginning to have serious questions. In meetings and movement offices, the guys would say, “hey babe, could you run this off on the mimeo” [mimeograph duplicating machine], or make some coffee, or file these papers that are all over the desks. (Actually we were writing the manifestos, as well, but that made no difference.)

Women had supposedly been freed up from the confines of the bourgeois home, and thus “available” for repeated one-night stands – that was “free love,” and if you said you wanted more that was soooo “bougie.” And if a woman had trouble speaking up at a meeting, she had “a problem.” Or if you did speak up, no one would listen to you. Or if they did listen, they would steal your idea and claim it as their own. Or if you had trouble finding childcare in order to come to a meeting, that was a “personal problem.”

Kirkpatrick Sale, in his history of SDS, quoted a woman who summed this up:

“We were still the movement secretaries and the shit-workers; we served the food, prepared the mailings and made the best posters; we were the earth mothers and sex objects for the movement men. We were the free movement ‘çhicks’ – free to screw any man who demanded it, or if we chose not to – free to be called hung-up, middle class, and up-tight. We were free to keep quiet at meetings – or if we chose not to, we were free to speak up in men’s terms…. We found ourselves unable to influence the direction and scope of projects. We were dependent on the male for direction and recognition.”

Plus in SDS there were these macho guys stomping around. It was the beginning of the Weatherman tendency and the emergence of leaders like Mike Klonsky and Bob Avakian and Mark Rudd. They would go swaggering around, calling girls “babe” and “chick,” and their idea of being revolutionary was going up against the cops in street battles, didn’t matter for what or what the outcome was. Now this was a mixed bag, because at the same time you had a growing radicalization. You can see it in documentaries like Columbia Revolt, when SDS took over Grayson Kirk’s office (he was the president of Columbia University) and found the documentation of the university “ivy tower’s” intimate collusion with the CIA. But a whole lot of swagger went along with that.

The language of the New Left and the Black Panthers reeked with male chauvinism and incredible backwardness. So when the objections of women in SNCC began to appear, Stokely Carmichael made his famous statement, “The only position for women in SNCC is prone” – on your back. Eldridge Cleaver began talking about “pussy power” and that got taken up by Panthers around the country. At the July 1969 SDS convention in Chicago – the famous “split convention”2 – Chicago Black Panther Party leader Fred Hampton’s deputy, “Chaka” Walls, repeated and even chanted that garbage about how the way women had rights in the movement was through “pussy power.”

It was disgusting, but the Weathermen, even the women, were so into guilty white liberal vicarious black nationalism that they didn’t say a peep about it. It’s interesting that at the same time, Elaine Brown came up to Berkeley from Los Angeles and ran into this filth and blew up, saying you wouldn’t hear Bobby Hutton3 saying this, or Geronimo ji Jaga (Pratt). Yet many Panthers were early on still saying things like a woman’s revolutionary duty is to sleep with the brothers, to have babies. And in the early years even this proud woman largely defined herself through men.

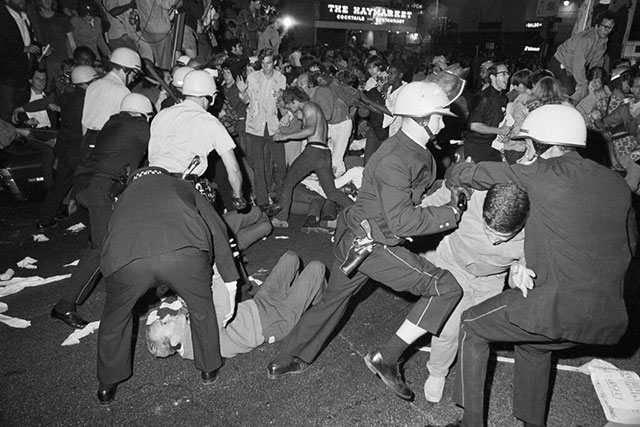

For me, I think, the turning point was Chicago ’68 at the demonstrations outside the Democratic Party convention, when thousands turned out to protest Hubert Humphrey, Lyndon Johnson’s vice president who became the presidential nominee, and the architects and war criminals who were carrying out the Vietnam War. This was a war of the Democratic Party, as most of the U.S. imperialist wars have been. So some people invaded the floor of the Convention and the Chicago cops came in swinging – the image of bodies being thrown through plate glass windows – and the enormous protests outside in Lincoln Park where protesters clashed with the cops deep into the night, the sounds of paddy wagon alarms and ambulances for the injured.

As tens of thousands of antiwar protesters gathered outside the Democratic convention in August 1968, police charged into the crowds, beating many bloody. (Photo: Bettman Archive)

At the church in the evening where a meeting was held, trying to evaluate where is this going – it was like, you throw a stone at a cop, and he clubs you bloody with his billy club, the casualties are piling up . . . and they said, “We’ve struck another blow against the empire.” Anybody who thought there must be another way was “chickenshit” – especially women who didn’t like all the macho posturing. (Of course there was another way, the real power against the cops’ repression is the power of the working class – fighting for labor strikes against the war to shut down the wheels of society.)

There were the beginnings of discussion among women in the movement: Why were we fighting for “everybody else’s” liberation and treated without respect?. What is this male supremacy that pervades the movement? How free am I with “free love”? So there began to be meetings about this, and informal collectives sprang up. A group called “Radical Women” in New York, and then Redstockings. The name is a play on the early suffragettes who had been called Blue Stockings. In Boston, Jan’s first wife was in a group called “Cell 16,” which became pretty famous – it even included Abby Rockefeller, of the Rockefeller family.

There began to develop a methodology called “consciousness-raising.” And that “the personal is political.” You didn’t have a “personal problem” if you were reduced to doing the grunt work in the office, or complained about machismo, or worried about how you were going to feed your kids when the guys were running around to demonstrations. We began to see all of these feelings and experiences as manifestations of a system of male supremacy and women’s oppression. They were legitimate and important to talk about.

It’s hard to explain today, but at the time there was no women’s movement. No one referred to “women’s oppression.” Things we talk about today as if they are commonplace – these concepts simply didn’t exist. All the frustration and anger boiling up in these “speak bitterness” sessions, it was what Betty Friedan called “the problem that has no name.” It was an aha! moment as you began to re-evaluate everything in your life. Career choices, life choices, your mother’s life, your grandmother’s. What your mother taught you and why: what kind of society was she living in, what were her options? This was the discourse in the early women’s movement.

Questions of sexual oppression and exploration were very important. There was Anne Koedt’s 1968 essay on “The Myth of the Vaginal Orgasm,” which goes back to Freud’s misogynistic theories about female sexuality. It was a revelation to us. Is it amazing in this day and age to talk about the fact that it is a myth? And talk of “penis envy,” another legacy of Freud that was used to put down women and deform our self-awareness. Then there was the publication of Our Bodies Our Selves, by a women’s health collective in Boston, one of the first books about women’s sexuality and health that came out of the women’s movement. It had become OK and important to talk about these things.

There was also a very important book, which I can’t get into in this talk, Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook – her fictionalized secret notebooks about her experiences, of racial oppression in Southern Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, and then in the British Communist Party, and the impact of the revelations of Khrushchev’s secret speech at the 20th Soviet Party Congress in 1956, when he admitted that Stalinism was built on lies. We all read this avidly. But, of course, Lessing didn’t address the central lie, the anti-Marxist dogma of “building socialism in one country” and everything that flowed from that, the popular front to block revolution, but also the betrayal and rolling back of gains for women as Trotsky talks about in his chapter on “Thermidor in the Family” in The Revolution Betrayed.

Politically, as Charlie mentioned in his talk last week, there was the emergence of different theoretical trends in the movement. Did women’s oppression originate in patriarchy? Was patriarchy there before private property and would it last after the overthrow of capitalism? Was male chauvinism in men’s DNA or in the system? Were men the enemy? Were male workers also oppressed?

One of the readings for this session was the 1969 Redstockings Manifesto, a document that has almost everything upside down: “We identify with all women.” “Women are an oppressed class.” “We identify the agents of our oppression as men.” “Male supremacy is the oldest, most basic form of domination. All other forms of exploitation and oppression (racism, capitalism, imperialism, etc.) are extensions of male supremacy….” And so on. Engels knocked down the theoretical basis of all this. There were also some truisms, but generally cloaked in terms of blaming men, in general: “We also reject the idea that women consent to or are to blame for their own oppression. Women’s submission is not the result of brain-washing, stupidity or mental illness, but of continual, daily pressure from men.” It rejected “existing ideologies as they are all products of male supremacist culture,” saying: “We will not ask what is ‘revolutionary’ or ‘reformist,’ only what is good for women.”

I was a member of Redstockings in New York for a few months while I was writing for the Guardian. Others have told me that I was always pushing from the left. In particular, I was concerned about the fact that the group was overwhelmingly petty-bourgeois and entirely white. Mainly what was important about it in terms of the radical women’s movement was the importance of the consciousness-raising sessions, where women talked freely about the ways in which they experienced oppression. The group included many who become well-known writers, critics and professors and a number of Greenwich Village intellectuals. So while it may loom large in histories of feminism, it wasn’t that influential among radical women activists who basically came from the New Left. I, for example, was mainly involved in the SDS split, which took place just as the Redstockings Manifesto was published.

And the limitations of the New Left were mainly what determined the fate of the radical women’s movement, which from the early ’70s on moved progressively to the right in sync with the rightward movement of American society. After a period of radical leftward motion, it was necessary to find a revolutionary political program and go forward to the fight for power, to bring down capitalism, or else the movement will be defeated and go the other way. So after the implosion of the New Left, the destruction of the Black Panthers and the decline of the antiwar movement, you had SDS leaders like Tom Hayden and Carl Davidson becoming Democratic politicians, Hayden a leader of Progressive Democrats of America, Davidson the founder of Progressives for Obama.

Meanwhile, Redstockings and most of the women’s groups consolidated around various gradations of anti-Marxist theory in order to justify a thoroughly pro-capitalist program. Many got sucked into bourgeois organizations like the National Organization for Women (N.O.W.) led by Betty Friedan and NARAL, which used to be the National Abortion Rights Action League until they got so right-wing that any mention of abortion was toxic for them and it became NARAL Pro-Choice America. As Marlene Dixon put it in her 1977 essay on the demise of the radical women’s movement, “the remnants of Women’s Liberation have come to be dominated by a middle-class leadership, reducing a vigorous and radical social movement to a politically and ideologically co-opted reformist lobby in the halls of Congress.”

And after leftist groups like the by-then thoroughly reformist Socialist Workers Party spent years building liberal pressure groups like N.O.W., opposing our call for free abortion on demand because it was unacceptable to Democratic politicians like Bella Abzug, they were chucked out on their ears in an orgy of feminist red-baiting. The bourgeois and petty-bourgeois feminists focused on achieving privileged positions for themselves, and won some gains. For working and poor women, not so much. There was an explosion of the number of women lawyers and doctors, and – while complaining about the “glass ceiling” and the practice of putting women execs on the “mommy track” – they even got to have some heads of capitalist companies, like Republican Carly Fiorina, whose claim to fame as CEO of Hewlett Packard was firing 30,000 workers.

From left: Gloria Steinem (at the 1972 Democratic National Convention), Andrea Dworkin, Catherine McKinnon. (Photos, from left: Associated Press; Stephen Parker; Gal Hermoni)

Laura

Kipnis (Photo: Chicago

Tribune)

Laura

Kipnis (Photo: Chicago

Tribune)Some of the bourgeois feminists went so far to the right that they made common cause with outright reactionaries, like Andrea Dworkin and Catharine McKinnon who joined with Gloria Steinem to launch a crusade to criminalize pornography. Steinem is the “ex” CIA asset who was infiltrating student groups and spreading anti-communism for the Agency while calling herself a radical feminist.4 Now University of Michigan law professor McKinnon and other feminists are pushing to use campus sexual harassment codes to strengthen university repressie powers over students, while repressing critics like professor Laura Kipnis at Northwestern who dares to complain that these codes infantilize women. This feminist-police alliance, turning campus administrators into sex cops, is the apotheosis of bourgeois feminism as the enemy of the genuine liberation of women.

It has reached the point where feminist arguments were used to justify imperialist war, in Yugoslavia in 1995 when NATO bombed Bosnian Serbs, accused of “genocidal rape” although there were cases of rape by all the contending armed forces; and in Afghanistan from 2001 on, when the U.S. pointed to the confinement of women as a justification for its continuing war on the Taliban. Or consider how Secretary of State Hillary Clinton posed as a benefactor of Haitian women in opening a sweatshop (financed by U.S. funds she siphoned off from earthquake relief aid). Oh, and don’t forget Hillary’s leading role in pushing through the grotesquely named 1996 “Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act,” intended to “end welfare as we have come to know it,” which threw several million mainly black women into poverty.

No “sister” to Haitian women workers toiling for starvation wages: Hillary Clinton, then U.S. secretary of state, visiting a garment sweatshop in the Sae-A industrial park in northern Haiti that she financed with money taken from earthquake relief funds, October 2012. (Photo: Kendra Helmer/USAID)

Meanwhile, the expansion of the number of women workers in the U.S. has been due to a significant degree to the decline of male workers’ wages, is overwhelmingly into low-wage McJobs and working at Walmart, puts additional pressure on working mothers, particularly single mothers, and now is declining (the U.S. used to be 7th in terms of the percentage of working women and now has fallen to 20th), in good part because of the soaring cost of childcare. So feminism hasn’t done so well for poor and working women.

I want to make a point here about some of the gains that were made. The right to legal abortion was the result of a Supreme Court decision, Roe v Wade. So why did those nine wealthy men in their black robes come to their decision? It was not because of lobbying Congress or demonstrations of the bourgeois women’s groups like N.O.W. and NARAL. It came about because the country was blowing up, the U.S. was losing the war in Vietnam, hundreds of thousands were in the streets protesting it, the black ghettos were exploding in upheavals from coast to coast, factory workers were striking at an alarming (to the bosses) rate, the army was disintegrating. Tens of thousands saw themselves as communists and revolutionaries. In the same period, the Court put the death penalty, that holdover from slave days, on hold. The bourgeoisie was worried about losing it all. That’s why gains for women were made, because of broader social struggle.5

But the women’s movement degenerated into “sectoralism,” as did the black movement, a process aided by the bourgeoisie. Black power was replaced by “black empowerment” for a select few. There was a Women’s Bank in New York and other locations. Virginia Slims cigarettes had ads with the slogan, “You’ve come a long way, baby.” Ms. Magazine, founded by Steinem, hit half a million in circulation. And only women could fight for women, supposedly, because for the feminists the enemy was men, not capitalism. After the 1969 Stonewall rebellion, the gay rights movement also quickly became sectoralist. Starting from a point where the concept of “women’s liberation” or “women’s oppression” were unheard-of ideas, it had now evolved into another “sector” of multi-vanguardist struggle which various opportunist leftists would tail after uncritically. And now most of the limited gains for women and African Americans are being rolled back.

What was needed was a revolutionary strategy, of class struggle uniting all the oppressed with workers’ power to achieve real women’s liberation through socialist revolution.

So this brings me to the crux of this talk.

In 1969, the Guardian newspaper split under the impact of the SDS split – Weatherman; what was called RYM II (Revolutionary Youth Movement II, led by Avakian and Klonsky); PL (Progressive Labor), and so on. The various components were different variants of Maoism. I moved to California while writing for something called The Liberated Guardian which lasted a couple of issues, and I reported on a strike by the ILWU (West Coast longshore and warehouse union). But mainly I went to do work in the women’s movement. When I got to the Coast, I actually tried to join the RCP, which was then called the Revolutionary Union – Avakian came out of Berkeley, and his father was a judge in super-rich Marin County. But I couldn’t join, because they claimed the family was the fighting unit for socialism, and they sure didn’t want me stirring up trouble among the women Maoists.

In my group of co-thinkers in the radical women’s movement, we were developing a critique of bourgeois feminism. What was wrong, we thought, with the women’s movement, was that it was petty-bourgeois. Which of course, it was – mostly educated women, no attention being paid to economic demands. And in particular, no black women. Why was that? Well, in large part because of the black power movement, but there was another factor involved. While the family is the core unit of bourgeois society, and the central locus of women’s oppression, as Marx and Engels noted in the Communist Manifesto, the family was already being destroyed for the working class.

This was and is doubly true for African Americans, because the family unit was legally broken up, first under slavery when slaves were often forbidden to marry, then under Jim Crow, and later under the welfare laws which prescribed no food stamps or aid to families with dependent children if there was a guy in the house. And now we have the school-to-prison pipeline. The feminists had no answers on these vital issues, since for them the problem was men. Marxists, however, have a program, to supersede the family, to replace it by social institutions for free childcare, education, laundries and other means of eliminating the enslavement of women in the household. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

So we thought: the way forward was to proletarianize the women’s movement, that is, to change it through demography, not program. And where would you go to reach and talk to working-class women? The phone company.6 At that time there were telephone operators who put through all the long-distance calls. And this was Oakland, California, where the calls to troops fighting in Vietnam, or on leave in Bangkok or Manila, were put through from the Oakland office of the telephone company.

We had a collective by then of radical women, East Oakland Women, and we got jobs in two places: the Owens-Illinois glass factory where some in our group got jobs putting together cardboard boxes to ship cooking wares; and in the telephone company building in downtown Oakland, where you had hundreds of women working the overseas lines in three shifts. Who were these women? A lot of the black women were in, or were relatives of or friends of people in, the Black Panther Party. A lot of the white women were part-time Berkeley students or women from the Chicano community and the developing political organizations there. It was a pretty wild place politically.

25th anniversary reunion of East Oakland Women in Oakland, June 1994. Marjorie in front, left. (Spartacist photo)

And we started Oakland Women’s Liberation. I was concerned, once again, about the need to win black working women. O.W.L. was an umbrella group of collectives – working women, health groups, art collectives, etc. At its high point, O.W.L. grew to 150 or 200 members. In the phone company we started an organization called the Operators Defense Committee, which fought for the rights of women phone operators. As phone workers we were all in Communications Workers of America (CWA) Local 9415 in the East Bay.

We were unionists, we were radicals, we were feminists and revolutionaries, and we saw no contradiction. For several years we never had a single guy in our meetings, of course. We hardly talked to men. We thought we were doing OK politically – we were growing. We did some crazy stuff and silly stuff.

This was a national phenomenon – there were political collectives all over the country coming out of the breakup of SDS, Marxist collectives, women’s collectives. And under the impact of the French upheaval and general strike of May 1968, almost all these collectives oriented to the working class and sought to deepen their understanding of Marxism.

In the Bay Area, the most prominent factory was the General Motors plant in Fremont. So when auto workers struck in September 1970, several dozen Berkeley radicals drove down there and hundreds of workers joined them, taking over the union hall and cheering militant speeches. In Detroit you had the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, with units in the Dodge Main plant (DRUM), Eldon Avenue (ELRUM), Ford River Rouge (FRUM). The League also controlled the student newspaper at Wayne State, The South End, which ran a slogan under its masthead, “One class-conscious worker is worth 100 students.” So much for all the student power nonsense we hear from latter-day Maoists today.

Also in the phone company in CWA Local 9415 there was another caucus – the Militant Action Caucus (MAC) – which was supported by the Trotskyist group, the Spartacist League. For about three years, we fought out our ideas, coming to no real resolution, because they couldn’t be tested. We had a feminist strategy, we thought that consistent feminism leads to socialism; they were Marxists. We were male-exclusionist, they were inclusive.7 We didn’t see any contradiction between Maoism and Marxism, or between Marxism and socialist feminism. And it all remained in the sphere of ideas.

So cut to the chase: 1971. This was the litmus test, where ideas got played out in action.

The CWA went on strike, as did the other union in the phone company – the IBEW (International Brotherhood of Electoral Workers) – that did a lot of construction and laying telephone wires in the underground tunnels, overhead wiring and also some repair work. It was a classic white male “job trust.” The jobs were craft jobs in the skilled trades, higher paying, requiring knowledge of electricity, passed down through the labor bureaucracy through family and neighborhood and “ole boys’ ties.”

First in 1971 was the CWA strike. Our local was very active – we were all out on the picket lines. We wildcatted to stay out after the strike was settled nationally, and the bureaucracy moved in to try to smash oppositionists in our local. After the strike was defeated, a sense of demoralization set in, as it does in periods of defeat. We just couldn’t get anything going. We were charged with “bringing the union into disrepute” mainly for being communists. Jane Margolis of MAC was particularly subject to victimization.

Then in the midst of this, there was a second strike, by the IBEW, the male job-trusting union. And we experienced a lightning bolt of shock. What was our strategy at that time? What did we think we were doing? We had a kind of Maoist-feminist strategy, that correct politics flow through the blood of true feminism, and that consistent feminism leads to socialism. That if you organize women around their own demands, they’ll come to a full understanding of the social struggle.

But the opposite was happening, in this litmus test. We saw the women we had recruited into our feminist consciousness-raising groups scab on the IBEW strike, crossing the picket lines of the men workers, and even worse, using the arguments that we had given them. Arguments that “we’re the most oppressed – we earn much less money, so we don’t have to honor their strike.” Or “that union never fought for women, so we don’t have to support that strike.” This really shocked us because we had been organizing women on a feminist strategy around their own oppression, thinking that it would lead them to join with the whole of the working class. But instead, it led to . . . strikebreaking.

So, in a state of shock, we immediately put out a leaflet from the Operators Defense Committee calling for solidarity with the IBEW strike. We participated in the picket lines and demanded nobody cross the lines. But in order to hold the class line, we were forced to break with many of the feminist constructs that we had previously held and come to grips with the contradictions we didn’t see before.

After the strikes we were in a state of ideological confusion. The MAC caucus suggested we have some joint discussions and we could evaluate the strike and the way forward. They suggested reading Lenin’s What Is to Be Done? and “Left-Wing” Communism. We said OK. Lenin seemed like a neutral ground. We were still Maoists, but what the hell, everybody could read Lenin.

By the way, MAC had tried to meet with us around two years earlier, but we didn’t, because of a tactical error. They wanted to send a guy to our meetings – and we refused. So they stood on principle and went away – a mistake. If a group is moving leftward, as we were, you should always find a way to engage them if you can.

I think about a year went by in our discussions with MAC and with the Spartacist League and our “rediscovery” of genuine Marxism, namely Trotskyism. That included an understanding that feminism and Marxism are counterposed, not complementary. An understanding that revolutionary consciousness comes “from the outside” in a dialectical interaction with the working class. An understanding that a revolutionary program must raise demands for the special oppression of women, and black people, that it raises the voices of the oppressed, but that it can make no sectoral divisions.

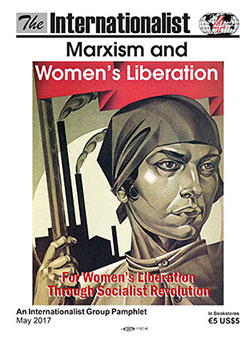

Articles

from Women and Revolution on “Foundations of

Communist Work Among Women: The German Social Democracy,”

“Early Communist Work Among Women: The Bolsheviks” and

“Feminism vs. Marxism: Origins of the Conflict,” are

reprinted along with many other key texts in the

Internationalist Group pamphlet, Marxism and Women’s

Liberation. Order a copy (98 pp., US$5, includes

postage) by clicking here,

or read it online by clicking on the image.

Articles

from Women and Revolution on “Foundations of

Communist Work Among Women: The German Social Democracy,”

“Early Communist Work Among Women: The Bolsheviks” and

“Feminism vs. Marxism: Origins of the Conflict,” are

reprinted along with many other key texts in the

Internationalist Group pamphlet, Marxism and Women’s

Liberation. Order a copy (98 pp., US$5, includes

postage) by clicking here,

or read it online by clicking on the image. And we had to “discover” that the program for women’s liberation was not new. It had been “discovered” by a whole generation of revolutionary women in the Communist International and the Bolshevik Party. We read Kollontai and Zetkin and these incredibly radical women who went before us. A particular influence was learning about the Bolsheviks’ work among women. Dale Ross was working on some articles on this, which I think you will be reading as well in this study group, that were published in Women and Revolution, which was put out by the Women’s Commission of the Spartacist League. Which, by the way, included male comrades as well.

Why had Stalinism buried this work? Well, the political counterrevolution led by Stalin held that socialism had been achieved in the Soviet Union. This corresponded to the interests of the emerging bureaucracy that wanted to preserve its relative privileges atop the workers state. The emancipation of women requires enormous economic resources, and Russia was an economically backward country, desperately poor and predominantly peasant, recovering from a terrible civil war in which it was attacked by 14 imperialist and capitalist armies. And although the Bolsheviks had made important advances, they were not able to transcend the family with universal collective day care, laundries, restaurants and the like. And if the family had not been transcended, if women were still trapped in the home in what Engels called that domestic drudgery, conservatism and stultification, then that was socialism, according to the Stalinists. All the Stalinists, including the Maoists! It was a big lie.

Another “discovery,” if you will, was that Maoism – which we were infused with, in the sense of the pervasiveness of the popular front and Stalinoid ideas – wasn’t Marxism. Of course, it helped that the Maoists at the time opposed women’s liberation (despite claims to the contrary) and glorified the family, as I mentioned. They also vilified gays and lesbians, calling homosexuals “sick.” Their heirs today have tried to clean up their act, claiming to stand for “proletarian feminism.” But it is still a sectoral conception, and they still uphold the family, and therefore they pose an obstacle to the liberation of women. “Wages for housework,” like various “proletarian feminist” groups call for, doesn’t lead to socialism. We had to deal with that reformist nonsense in the early ’70s as well.8 We fought for the socialization of household tasks.

Interestingly, as we moved left, the organization we had built, Oakland Women’s Liberation, was in the process of dissolving. Partly because of the change in the period. Partly because, once we had real Marxist ideas, we found a lot of the women didn’t want to hear them. We were “taking up their space” with our “male-dominated ideas.” And so forth, I’m sure you hear this sort of stuff today.

After about a year of intense reading, and a fairly rocky road, we embraced Trotskyism, the continuation of Marxism and Leninism in our time. This involved studying the role of Stalinism in sabotaging struggles in the ’30s, the ’40s with the popular front, Stalin’s betrayal of post-WWII revolutionary struggles in Greece, Italy and France, the role of the Communist Party in France in 1968, and how all that shaped the world we live in today.

This was one of the last hurdles we faced, the “rediscoveries” that involved rethinking and “unlearning” everything we had learned before. You have a tremendous advantage today because you are learning genuine Marxism from the start, for example with the pamphlet of texts on Bolsheviks and the Liberation of Women published by the Internationalist Group.9 But the studying and learning never stops, of bringing our ideas into focus and testing them in practice. It’s a dialectical process that is the essence of Marxism. ■

- 1. In 1967, New York SNCC activist Kathleen Neal organized a radical student conference at Fisk University, at which she met Eldridge Cleaver, then Minister of Information of the recently formed Black Panther Party. The two got married and Kathleen Cleaver became one of the best-known Panther leaders.

- 2. At its 1969 convention, held in Chicago, Students for a Democratic Society split between rival Maoist-led factions, each waving the “little red book” of Quotations from Chairman Mao at the other.

- 3. “Lil’ Bobby” Hutton, as he was known in the Panthers, was one of the BPP’s first recruits, murdered by the Oakland Police Department at the age of 18. Geronimo ji Jaga Pratt was a leader of the BPP’s Los Angeles chapter who was imprisoned for 27 years as a result of a frame-up on phony murder charges that was part of the FBI’s notorious COINTELPRO campaign. (See “Geronimo Is Out! Now Free Mumia!” The Internationalist supplement, June 1997.)

- 4. Steinem was head of the “Independent Service for Information,” an entirely CIA operation, which specialized in subverting student groups. See “‘Democratic Socialism’ in the Service of U.S. Imperialism,” in the Internationalist pamphlet, DSA: Fronting for the Democrats (February 2018).

- 5. On the history of Roe v. Wade, and its overturn in 2022, see “Supreme Court Cancels Right to Abortion,” The Internationalist No. 67-68, May-October 2022, as well as “Free Abortion on Demand – How Revolutionaries Fight for It” and other articles in Revolution No. 19, September 2022.

- 6. Until the early 1980s the Bell System (often known as “Ma Bell”) had a government-sanctioned near-monopoly on phone service in the U.S.

- 7. The article “Class Struggle in the Phone Company,” Women and Revolution No. 5, Spring 1974, provides important background and details on several aspects of this history.

- 8. The demand for “wages for housework,” like Silvia Federici has been promoting, rather than abolishing women’s household subjugation through the communist program for replacing it with social institutions, was refuted in a polemic against the theories of feminist writers Selma James and Mariarosa Dalla Costa, in Women and Revolution No. 5, Spring 1974.

- 9. See also our extensive 2017 pamphlet, Marxism and Women’s Liberation.

Includes key texts by

Bolshevik leaders. Order a copy (US$3, includes postage) by

clicking

Includes key texts by

Bolshevik leaders. Order a copy (US$3, includes postage) by

clicking