November 2006

The Paris Commune, March-April 1871. (Engraving: Progress Publishers)

A

battle was won, but the war continues. And the outstanding fact about

the war

for Oaxaca is that, even though today it still takes the form and

raises

demands characteristic of a democratic struggle, underlying it

is the class

war. It all began with a teachers strike for rather modest demands

(above

all for rezonification1 for Oaxaca teachers). After June 14,

their main demand has been for the

expulsion of the murderous governor. In principle, none of this goes

beyond the

capitalist framework. Nevertheless, the struggle not only faces a

despotic cacique

(political boss), but the whole semi-bonapartist regime of the

Institutional

Revolutionary Party (PRI), which ruled Mexico uninterruptedly for 70

years and

is still intact in Oaxaca. The many thousands of political operatives

who ran

the single-party PRI-government in the state are still there, but now

deathly

afraid of losing their sinecures and facing the ire of an irate

populace.

In

reality, to bring down this regime and defeat its last-ditch defenders

will

take something approaching a political revolution. Moreover, the

struggle takes

place in a society characterized by a deep division between a narrow,

oligarchic

European-derived (criollo) ruling class, and a huge mass of

working

people largely of Indian origin. With this political and social

structure,

semicolonial in the strictest sense, “those at the bottom” cannot win

without

going outside the bourgeois-democratic framework and undertaking a

social revolution.

Replacing the governor to get another PRI politician, or even a

bourgeois

“independent,” in his place would not change much, with the possible

exception

of the level of repression – and maybe not even that. In order for

the

working people to win their struggle, the popular rebellion must turn

into

workers revolution.

Some

leftists are acting as if this has already happened. In recent weeks,

there has

been a spate of articles by “progressive” commentators in the bourgeois

press

and leftist groups referring to a “Oaxaca Commune.” This was the title

of an

article by Luis Hernández Navarro in La Jornada (25

July). Another by

the Agencia Latinoamericana de Información was titled, “The

Oaxaca Commune

Rises Up” (ALAI, 29 September). Iván Rincón Espríu

wrote about “Tlatelolco and

the Oaxaca Commune” in the Oaxacan daily Noticias (5 October).

“Mexico:

Long Live the Oaxaca Commune!” proclaimed the Trotskyist Faction (FT)

in a 6

September declaration, and more recently “Defend the Oaxaca Commune!”

The FT’s

Mexican group, the Liga de Trabajadores por el Socialismo (LTS –

Socialist

Workers League), refers to “The Oaxaca Commune on Alert” (La Verdad

Obrera,

5 October). “The Oaxaca Commune: APPO,” writes the Militante group (6

November). In Brazil on November 2 there were a number of “actions in

solidarity with the Oaxaca Commune.” On Radio APPO as well, announcers

often

say they are transmitting from the Oaxaca Commune, like Radio Habana

signs off

with the slogan “transmitting from the first free territory of America.”

Is

there a Oaxaca Commune? Let’s take a look at the key point of

reference: the

Paris Commune of 1871. Following the defeat of the army of emperor

Louis

Napoléon in the war against Germany and the proclamation of the

Republic in September

1870, the French capital continued to be besieged by the Germans. The

plebeian

population of Paris distrusted the bourgeois government, which was

enjoying the

pleasures of a golden refuge in the Versailles Palace. This government,

for its

part, feared the National Guard because of its proletarian composition.

When

the regime tried to dissolve the Guard on 18 March 1871, it rebelled

and the

Parisian workers suddenly found themselves in power.

The

image of a besieged revolutionary citadel is not totally alien in the

present

Oaxacan context, particularly today as it approaches a

near-insurrectionary

situation. At the same time, it is certainly not a very heartening

image, presaging

a bloody defeat. The Paris Commune was smashed after 72 days, with a

toll of

more than 30,000 dead and 50,000 jailed among the communards. This is

what Iván

Rincón Espríu was referring to in warning of the danger

of a repetition of the

1968 massacre in the Plaza de Tlatelolco, when the Mexican army

massacred

perhaps 500 students and leftists. “The troops who will try to smash

the Oaxaca

Commune and drown the popular discontent in blood and fire (in the

process

increasing it) have already located their attack points and have taken

up their

positions,” he wrote in early October.

March of the APPO arrives in Mexico City on

9 October. Banner calls for ouster of Oaxaca governor Ulises Ruiz

Ortiz.

March of the APPO arrives in Mexico City on

9 October. Banner calls for ouster of Oaxaca governor Ulises Ruiz

Ortiz.

(Photo: El Internacionalista)

Hernández

Navarro’s starting point is also valid: he writes that the movement

begun by

the Oaxaca teachers strike is the kind of social struggle that presages

others

of greater magnitude, like the strikes in Cananea (miners) and

Río Blanco

(textile workers) that were precursors to the Mexican Revolution of

1910-17.

His conclusion, however, is to add the Oaxaca rebellion to the struggle

against

“the cochinero [roughly, swinishness] carried out in the July 2

elections” – i.e., the López Obrador mobilizations under the

mantle of the

bourgeois PRD.

In the case of protests against repression

that seek

to express enthusiastic support to the heroic Oaxacan fighters, the

reference

is understandable. But when tendencies which claim to be Marxist and

Trotskyist

refer to a “Oaxaca Commune,” above all when they do so as praise and

glorification,

this demonstrates a dangerous theoretical and programmatic

light-mindedness:

instead of clarifying, it obscure the necessary lessons and measures to

win the

battle of Oaxaca. It distorts reality by conferring on it a

revolutionary

content that has yet to be realized, and it reveals that the authors

live in a

fantasy world. Even worse, in losing confidence in the working class as

the

vanguard, they look for substitutes: they replace the class struggle

with a

“democratic,” or rather, “democratizing,” outlook. Instead of the

dictatorship

of the proletariat, they call for “organs of self-determination of the

masses”

(LTS, Estrategia Obrera, 21 October).

What

was the Paris Commune? Among “the multiplicity of interpretations to

which the

Commune has been subjected, and the multiplicity of interests which

construed

it in their favor,” Karl Marx wrote in The Civil War in France

(May

1871), “Its true secret was this: It was essentially a working class

government, the product of the struggle of the producing against the

appropriating class, the political form at last discovered under which

to work

out the economical emancipation of labor.” Later on in the same text he

calls

the Commune a “workers government.” Engels repeats, in his 1891

introduction to

Marx’s work, “Of late, the social-democratic philistine has once more

been

filled with wholesome terror at the words: Dictatorship of the

Proletariat.

Well and good, gentlemen, do you want to know what this dictatorship

looks

like? Look at the Paris Commune. That was the Dictatorship of the

Proletariat.”

Those

who today refer to a Oaxaca Commune as “real democracy” or the

“self-determination of the masses” without class distinction trace

their

lineage not to the great revolutionary theoreticians but to the great

granddaddy of the opportunists, the “social-democratic philistine” par

excellence,

Karl Kautsky, who in his anti-Soviet screed Terrorism and Communism

(1919) distorted Marx’s words in describing the Paris Commune as “the

government of the people by the people, that is, democracy.”

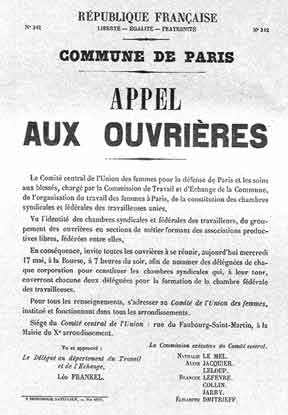

Appeal by the Paris

Commune calling for the election of delegates to a federal chamber of

women workers.

Appeal by the Paris

Commune calling for the election of delegates to a federal chamber of

women workers.

The

Paris Commune was a workers government, an incarnation of the

dictatorship of

the proletariat – two synonymous phrases – not because Marx and Engels

said so,

but because of its own self-conception, its composition and its

actions. The

proclamation of the Commune, the Declaration of the Central Committee

of the

National Guard of 18 March 1871, stated: “The proletarians of Paris,

amidst the

failures and treasons of the ruling classes, have understood that the

hour has

struck for them to save the situation by taking into their own hands

the

direction of public affairs.... They have understood that it is their

imperious

duty, and their absolute right, to render themselves masters of their

own

destinies, by seizing upon the governmental power.”

Marx

immediately added: “But the working class cannot simply lay hold of the

ready-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes.” The

proletariat

had to build its own government, in which “the majority of its members

were

naturally workers, or acknowledged representatives of the working

class. The

Commune was to be a working, not a parliamentary body, executive and

legislative

at the same time.” This was the main amendment Marx and Engels made to

the Communist

Manifesto since it was written in 1848.

So

let’s take a look at the Oaxacan situation today. The leading body of

the

struggle, the Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca, does not

define itself

as a government, nor is it one in fact. It is an organ of struggle,

whose leadership

consists of representatives of different organizations. Until now, the

large

majority of the delegates have not been elected but rather were named

by the

leaderships of the groups which make up the APPO. Its backbone is

Section 22 of

the SNTE-CNTE (the teachers union), and it includes various unions of

public

employees (workers of the secretariat of health, the Social Security

Institute,

the ISSTE, the University of Oaxaca, airports) belonging to the FSODO

(Front of

Unions and Democratic Organizations of Oaxaca), as well as telephone

workers

and bus drivers, along with semi-labor groups (Associated Women Trade

Unionists,

retired railroad workers) and leftist organizations (Frente Popular

Revolucionario, Comité de Defensa de los Derechos del Pueblo

[Committee for

Defense of the Rights of the People], Partido Obrero Socialista

[Socialist

Workers Party, now rebaptized the Movement for Socialism]). But it also

includes

a number of organizations of indigenous peoples – the Organization of

Indigenous Zapotec Peoples (OPIZ), the Popular Indigenous Council of

Oaxaca

(CIPO), the Union of Indigenous Communities of the Northern Isthmus

(UCIZONI),

Movement of United Triqui Struggle (MULT) – and peasant organizations.

There

is no doubt that the APPO has struck root in the Oaxacan masses by

having

resisted for so long the siege by state and federal governments and the

murderous violence of the thugs and paramilitaries. But it is not a

nascent

workers government. The APPO has a multi-class character, with a

petty-bourgeois leadership in which popular-front politics predominate.

The

decisions of the National Forum on Constructing Democracy and

Governability

called by the APPO last August 16 and 17, for example, called to

“generate

alliances with different sectors and political actors premised on our

main

demand: for the ouster of Ulises Ruiz Ortiz.” At the same time, it

urged “the installation

of a Popular Government Council” and the formation of a “Great National

Popular

Assembly.” For many in the APPO, these calls are directed at the PRD,

whose

representatives have had discussions with the APPO in Oaxaca in recent

days.

Spokesman of the Grupo

Internacionalista speaks to forum called by APPO in mid-August. PRD

supporters tried to shout him down.

Spokesman of the Grupo

Internacionalista speaks to forum called by APPO in mid-August. PRD

supporters tried to shout him down.

(Photo:

El Internacionalista)

To

be sure, the APPO and Section 22 have had to carry out certain

governmental functions,

constituting the Honorable Body of Topiles (a kind of popular

police,

derived from indigenous community organizations) and the Oaxaca

Teachers Police

(POMO) to maintain order in the occupied city, detaining thieves and in

some

cases submitting them to popular trials. But these are only episodic

organs and

measures of struggle of the sort that would arise in any general strike

that

lasted for a time.

It is also true that there are aspects of

dual power

with the occupation of the capital by the APPO and the installation of

popular

municipal councils in around 20 municipalities. But this is not dual

power of different

classes. The APPO has not made any moves against private property

whatsoever: it has not taken over hotels, or haciendas, factories or

transportation

companies. Nor has it seized federal government institutions, like the

highways

or airport. Above all, with its call for “peaceful” resistance against

the onslaught

by the forces of Ulises Ruiz and the federal government, it has not

called into

question the bourgeois state’s monopoly of armed force. In fact, in

negotiations with the interior ministry (Gobernación) APPO

leaders accepted in

principle the incursion of the Federal Preventive Police into Oaxaca.

In

December 1905, when Leon Trotsky was jailed as president of the

Petersburg

Soviet, he wrote a piece titled “35 Years Later: 1871-1906,” in which

he

stated:

“The Paris Commune of 1871 was not, of

course, a socialist

commune; its regime was not even a developed regime of socialist

revolution.

The ‘Commune’ was only a prologue. It established the dictatorship of

the

proletariat, the necessary premise of the socialist revolution. Paris

entered

into the regime of the dictatorship of the proletariat not because it

proclaimed the republic, but because out of 90 representatives it

elected 72 representatives

of the workers and stood under the protection of the proletarian guard.”

None of this exists in Oaxaca yet.

For now it

is Zukunftsmusik, “music of the future” to which we may aspire

and for

which communists struggle. But to confound our desires with actual

reality

would be fatal for the future development of revolutionary struggle in

Mexico.

There is not a proletarian power in Oaxaca, and for it to come into

being, the

struggle would have to be waged, not in the confines of a predominantly

peasant

and rural state bur instead by extending the insurgency to the big

battalions

of the working class in the capital of the country and the industrial

centers.

To achieve this, it is indispensable to forge a leadership, a party,

which

fights not for “real (bourgeois) democracy,” but openly for workers

revolution. n

See also:

To contact the Internationalist Group and the League for the Fourth International, send e-mail to: internationalistgroup@msn.com